Annual assessment of the forecasts included in GEO in 2023

Global Economic Outlook (GEO) provides a monthly overview of the latest economic forecasts from international institutions, selected central banks and Consensus Economics. The impacts of the ongoing war in Ukraine and the resulting energy crisis in Europe also affected the outlooks for last year, especially the longer-term ones. The optimism of the monitored institutions regarding the GDP growth outlooks for 2023 did not materialise in the case of the European states (except Russia), while the monitored non-European states and Russia achieved higher economic growth compared to the outlooks. Also, at the beginning of 2022, none of the monitored institutions expected elevated inflation for 2023 in the monitored states (except China). The outlooks for short-term interest rates at the one-year horizon for the euro area and the United States were accordingly underestimated. The volatility of the exchange rates of the monitored currencies against the US dollar has decreased, and the expected weakening of the dollar has not materialised at the longer end. Over the entire period under review, the forecasts had generally expected a slightly higher oil price.

Published in Global Economic Outlook – June 2024 (pdf, 2.1 MB)

Introduction

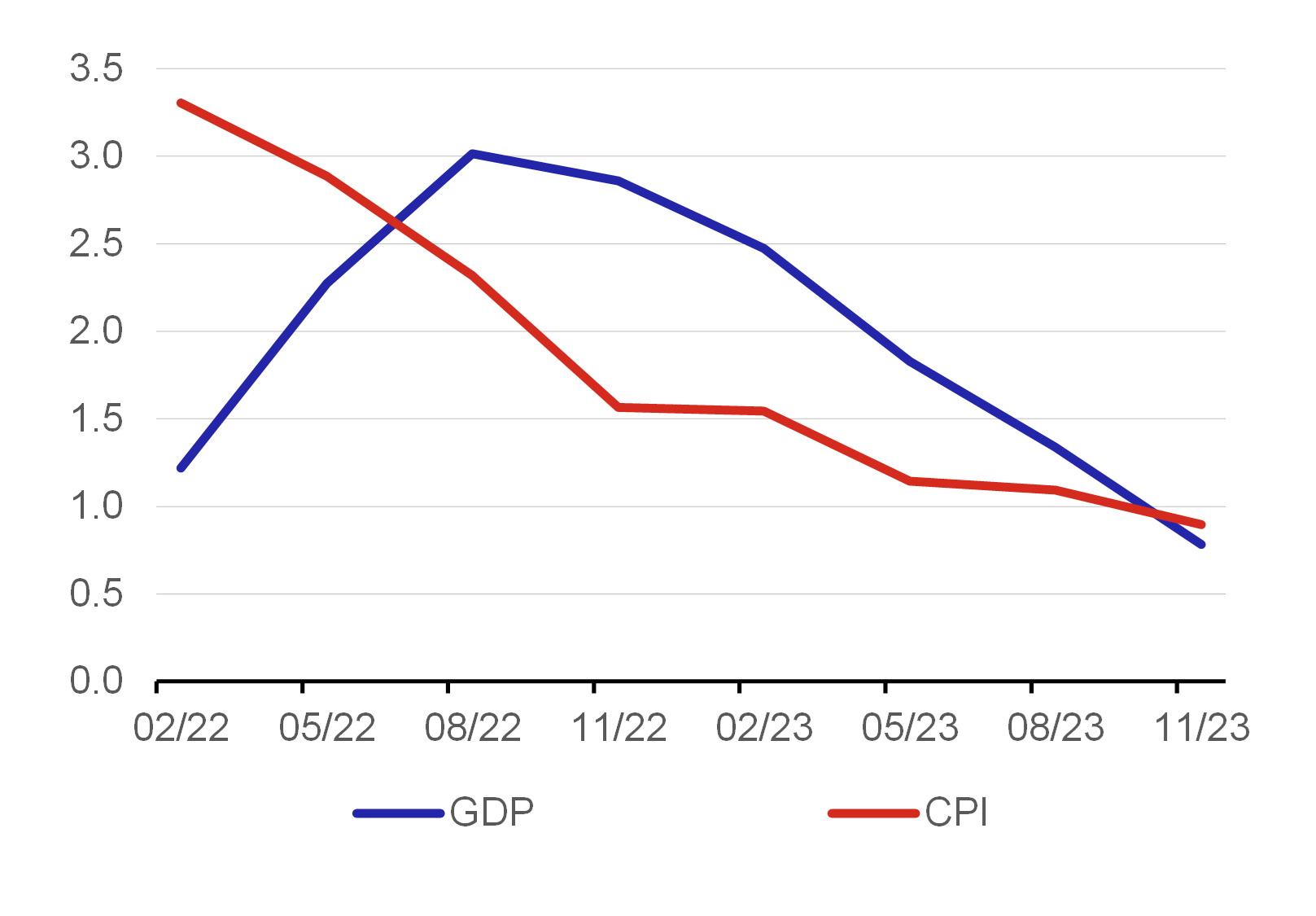

Every year, we assess the accuracy of the forecasts of economic variables regularly monitored in the GEO. The results of this assessment provide valuable information about which of the monitored institutions were closest in their estimates to the subsequently recorded reality and were therefore the most successful in their forecasts. For interest rate, USD exchange rate and oil price forecasts, we also assess, in addition to Consensus Forecasts (CF), outlooks derived from market contracts. The assessment always applies to the previous year. In the case of GDP growth and CPI inflation forecasts for the given calendar year (fixed-event forecasts), forecasts for 2023 are currently assessed. In the case of forecasts published for a fixed horizon, which shifts further into the future each time a new forecast is published (rolling-event forecasts), the assessment includes predictions starting in 2020. From the outlooks regularly published in the GEO, this category of rolling forecasts includes, for example, the three-month and one-year outlooks for foreign interest rates, the price of oil and the outlooks for the exchange rates of the monitored currencies against the US dollar. The general characteristics of the outlooks are quite clear – they become more accurate as the forecast horizon shortens (Chart 1). However, in the case of the GDP growth outlooks, there was initially an increase in the inaccuracy in the outlooks until mid-2022 owing to uncertainty regarding the impacts of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Chart 1 – Gradual improvement of forecasts for 2023

(RMSE average)

Source: authors‘ calculation

Note: All monitored institutions and all six regions (the USA, the euro area, China, the United Kingdom, Japan and Russia).

Owing to the shortness of the time series under assessment, the analysis mainly uses the simple mean forecast error (MFE). The forecast error et is calculated as the difference between the ex post known actual value at and the corresponding forecast ƒt: et=at – ƒt. A positive forecast error thus means that a lower value was forecasted for the given variable than the actual outcome (undershooting reality). By contrast, a negative forecast error means that the forecast value was higher than the subsequent outcome (overshooting reality). The Consensus Forecasts publication is the source of the actual GDP growth and consumer price inflation figures for 2023. The Bloomberg database is the source of the actual values of the other variables assessed – this also draws on futures for interest rates, exchange rates and Brent crude oil prices.

We also use the RMSE to assess the accuracy of the GDP growth and inflation forecasts across institutions. We also use the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) to assess the accuracy of the forecasts across the exchange rates of individual currencies against the US dollar. This indicator, given as a percentage, is suitable for the mutual comparison of variables of different dimensions. In addition, the individual errors are given in absolute terms and thus (as in the case of the RMSE) there is no mutual compensation of positive and negative forecast errors, as is the case with the MFE indicator. The formal notation is as follows:

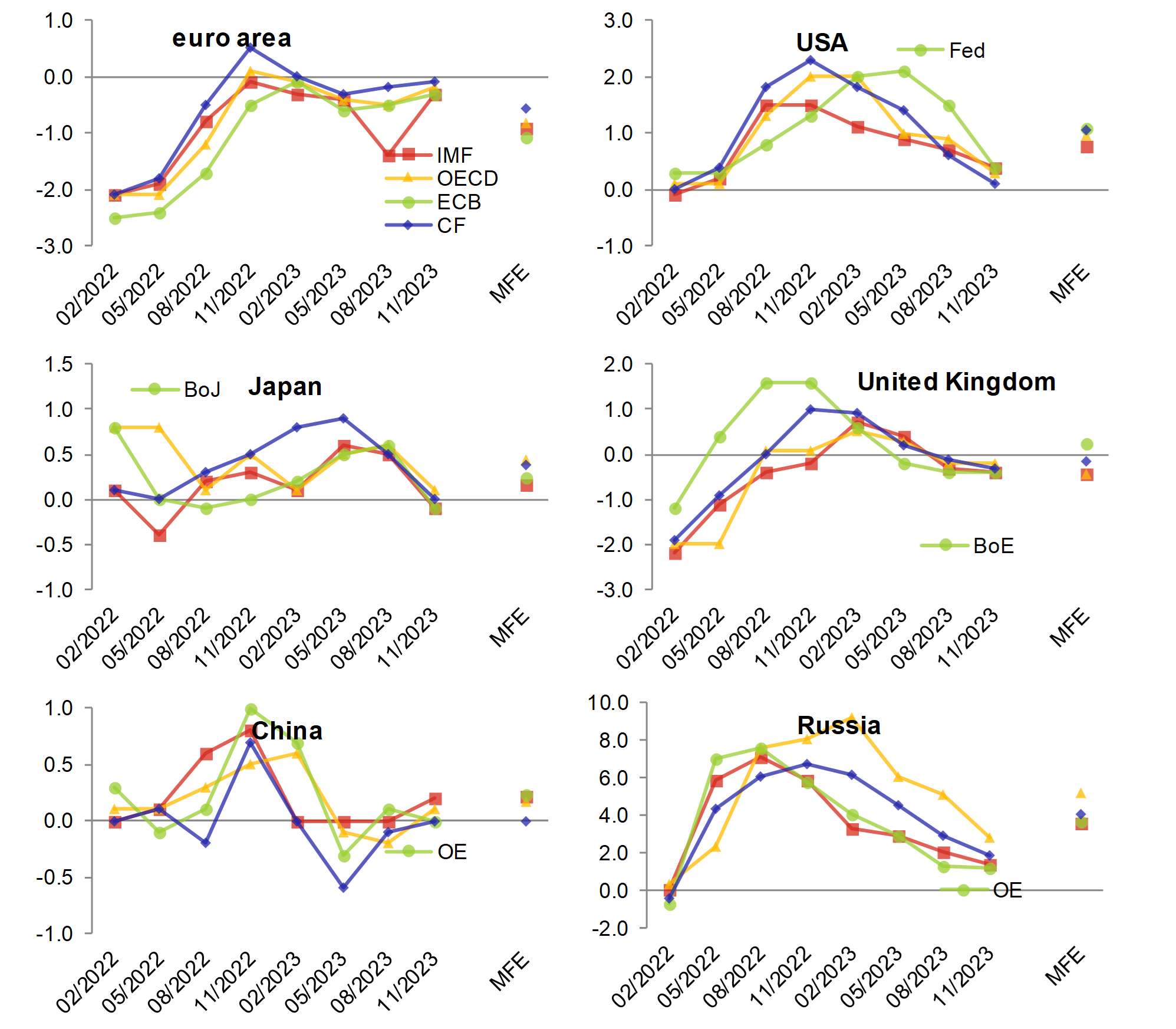

Assessment of the accuracy of the GDP growth and CPI inflation forecasts for 2023

In the GEO, we regularly monitor the development and forecasts of GDP growth and CPI inflation in the euro area, the USA, the UK, Japan, China and Russia. The GDP growth and inflation forecasts for these countries are taken primarily from the CF questionnaire survey, from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These three institutions cover all the states monitored. In the case of advanced economies, the forecasts of their central banks, i.e. the European Central Bank (ECB), the US Fed, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and the Bank of England (BoE), are also monitored. For China and Russia, Oxford Economics forecasts are used instead. The outlooks of the above institutions differ from each other in terms of the frequency of new editions during the year, and the publication dates. The frequency of forecast updates is either monthly (CF and OE forecasts) or quarterly (IMF, OECD, ECB, Fed and BoJ). The quarterly forecasts (the February, May, August and November forecasts) are assessed.

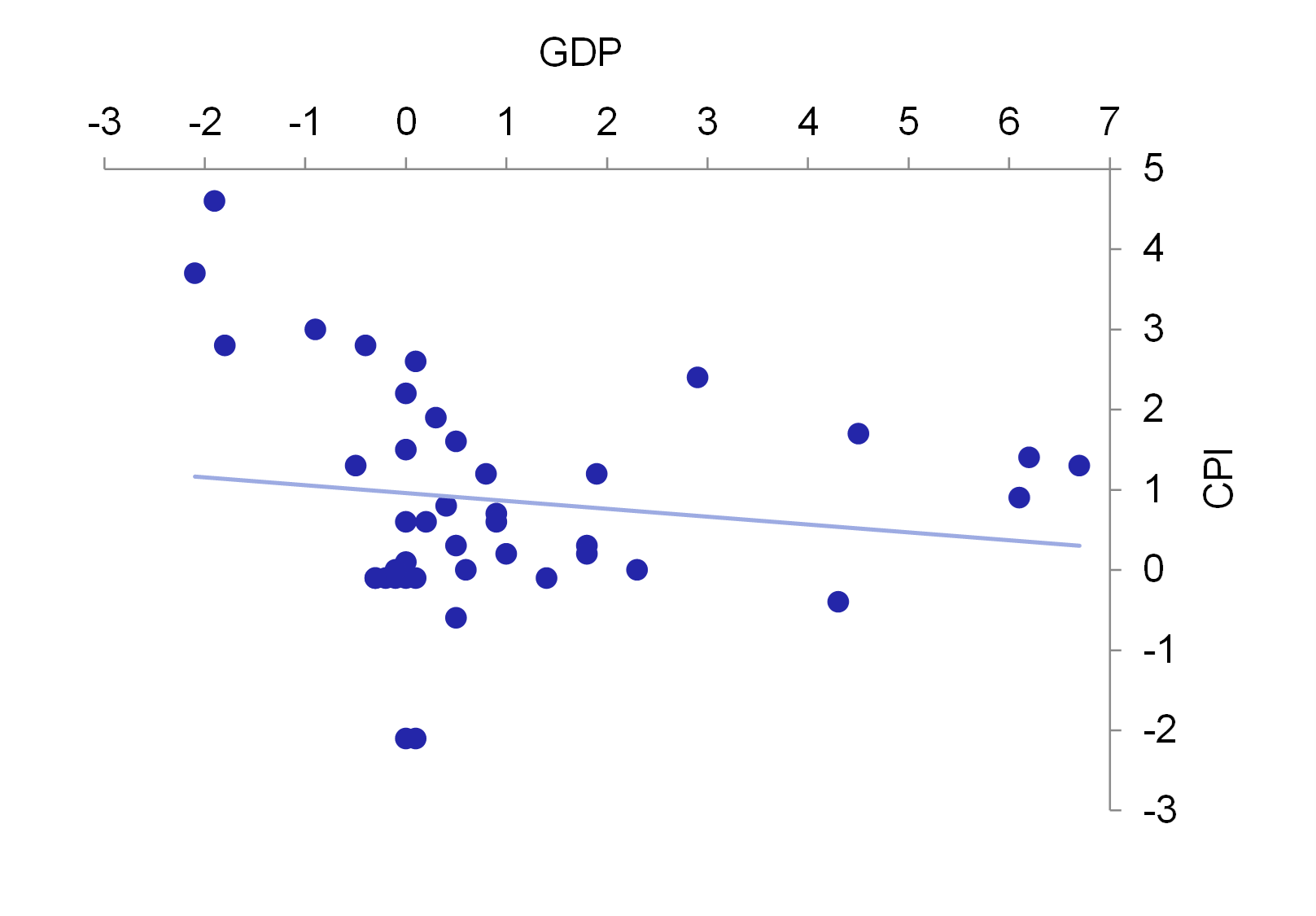

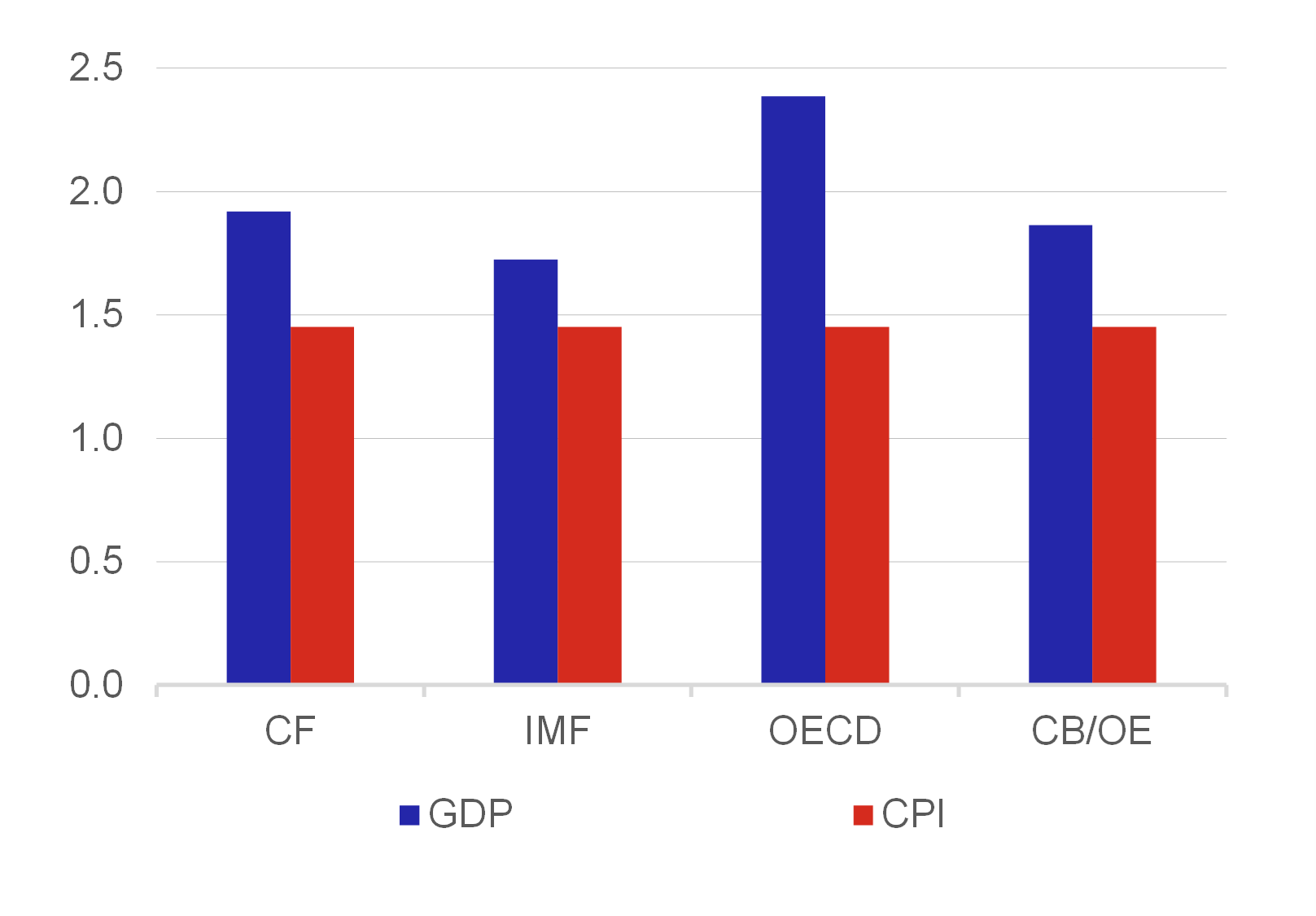

On average, expected economic growth was higher than the reality for the euro area and the United Kingdom, while for the USA, Japan, China and especially for Russia, the reality was a surprise with higher-than-expected figures. Thus, in the context of the war in Ukraine in 2023, the euro area and UK economies faced inconveniences with stagflation features, i.e. stagnation of economic growth amid rising inflation. There is therefore an obvious inverse relationship between the errors in the forecasts for economic growth and inflation for these states. Looking at the errors in the CF forecasts for all the states monitored, the inverse relationship seen in previous assessments is no longer evident (Chart 2). The deviations of the GDP growth forecasts for the states we monitor from the subsequent reality are shown in the charts in Annex 1. Russia had the greatest variability[1] in GDP growth and inflation outlooks. In its case, the monitored institutions expected the war to have much worse economic impacts. However, Russia's actual GDP growth for 2023 ended up being significantly higher (the second highest of all the states surveyed, after China). In Russia’s case, this was probably an effect of the war economy and the limited real impact of Western sanctions. The GDP growth outlooks for Japan and China were the most accurate (as measured by the RMSE indicator). In addition, both these states were characterised by low variability of the growth forecasts. With expected GDP growth for Japan of 1.8% according to the CF at the beginning of 2022, actual growth was only 0.1 percentage point higher in the end. In the case of the United States, at the beginning of 2022 the CF even showed the same GDP growth figure for 2023 that was eventually achieved. However, unfortunately, the CF (and other institutions) excessively worsened the expected US GDP growth during the forecast horizon. There were much larger differences in the euro area and the UK, both of which were hit hard by the war in Ukraine and the subsequent energy crisis. The difference between the first CF estimate of euro area GDP growth and the actual situation was 2.1 percentage points. The accuracy of the economic growth forecasts across all the states was very similar for all the institutions compared (Chart 3).

Chart 2 – Relationship between GDP and CPI deviations

(%)

Note: CF forecasts for the states under review.

Chart 3 – Comparison of the accuracy of institutions forecasting GDP growth and inflation for all countries

(RMSE)

Source: authors‘ calculation

Note: CF – Consensus Forecasts, IMF – International Monetary Fund, OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, CB/OE = central bank or Oxford Economics

Due to the war-induced energy crisis and lingering post-pandemic effects in particular, actual inflation (with the exception of China) exceeded its initial expected levels from the beginning of 2022 (Annex 2). Central banks' inflation outlooks were characterised by similar inaccuracy as those of other institutions (the Fed and the BoE had worse inflation outlooks). Russia and, to a lesser extent, the UK again showed the greatest inflation-forecast variability. In the euro area, average expected inflation for 2023 was 1.7% at the start of 2022, yet the actual figure was 3.7 percentage points higher. The CF analysts achieved the most accurate inflation outlooks for all states on average (Chart 3). However, more general conclusions cannot be drawn from the results for only one assessed year, as the accuracy of the forecasts usually changes over time and between individual institutions. However, the charts of deviations in GDP growth and inflation show a general pattern in which the forecasts are gradually refined as their time horizon shortens.

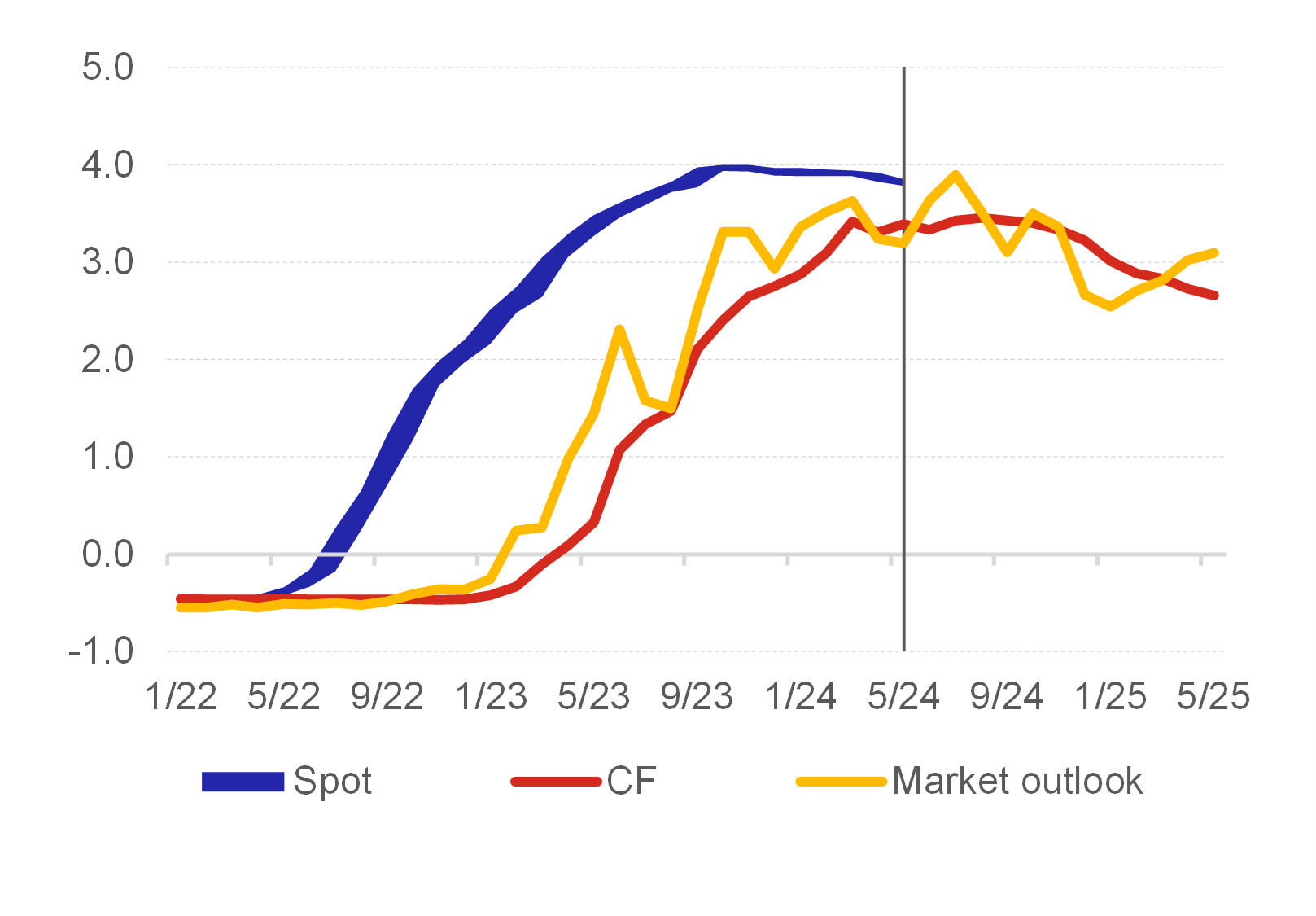

Assessment of the accuracy of foreign interest rate forecasts

The interest rate outlooks are monitored for the euro area and the United States in GEO. In addition to the CF outlook, the monitored outlooks for three-month interest rates are accompanied by outlooks derived from futures. By contrast, the outlooks for long-term (ten-year) government bond yields are taken from CF only. Last year saw inflation peak, and the end of 2023 in particular shifted optimistic expectations about the timing of major central bank rate cuts.

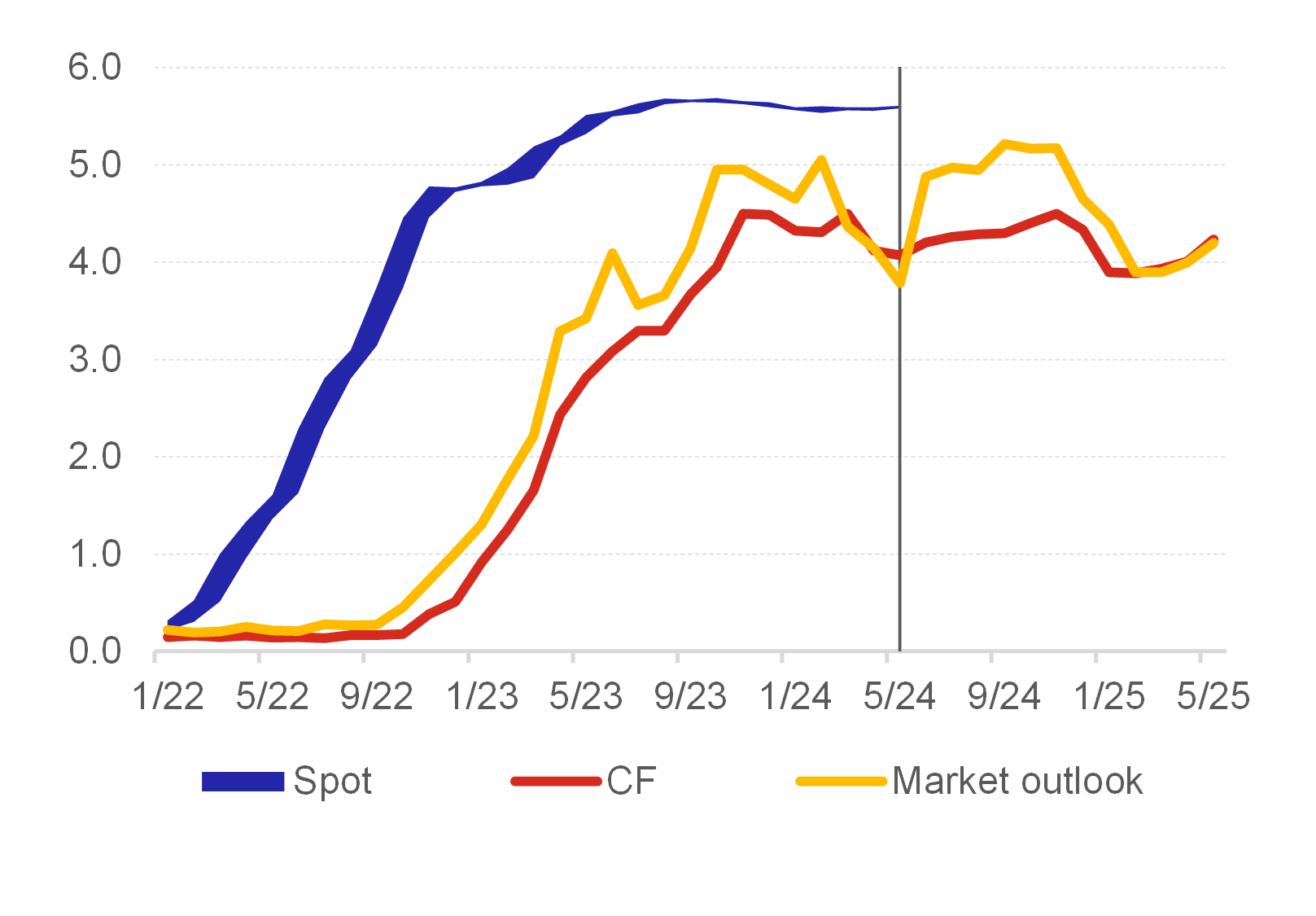

Short-term market expectations regarding the path of short-term interest rates were relatively reliable last year, yet not very forward-looking for the annual outlook (Charts 4 and 5). The rate hike process started around mid-2022, yet the expected pace of rate hikes reflected current developments rather than a forward-looking approach. The CF analysts were mostly more restrained than the markets on the future tightness of monetary policy by both the ECB (Chart 4) and the Fed (Chart 5), while at the same time the analysts did not expect the current rates level. Market expectations are showing greater volatility, i.e. greater sensitivity to information coming from the economy and a willingness to change the direction of the outlook, and this has been the case since the start of this year. In Chart 5 in particular, we can see a change in expectations regarding rate hikes in the spring of last year, when rates were already expected to fall at the one-year horizon (spring 2024).

Chart 4 – Annual outlook for three-month interest rates in the euro area and comparison with reality

(%)

Source: CF, Bloomberg

Note: The blue area denotes the range of the minimum and maximum price in the given month. The vertical line denotes the end of the observed data.

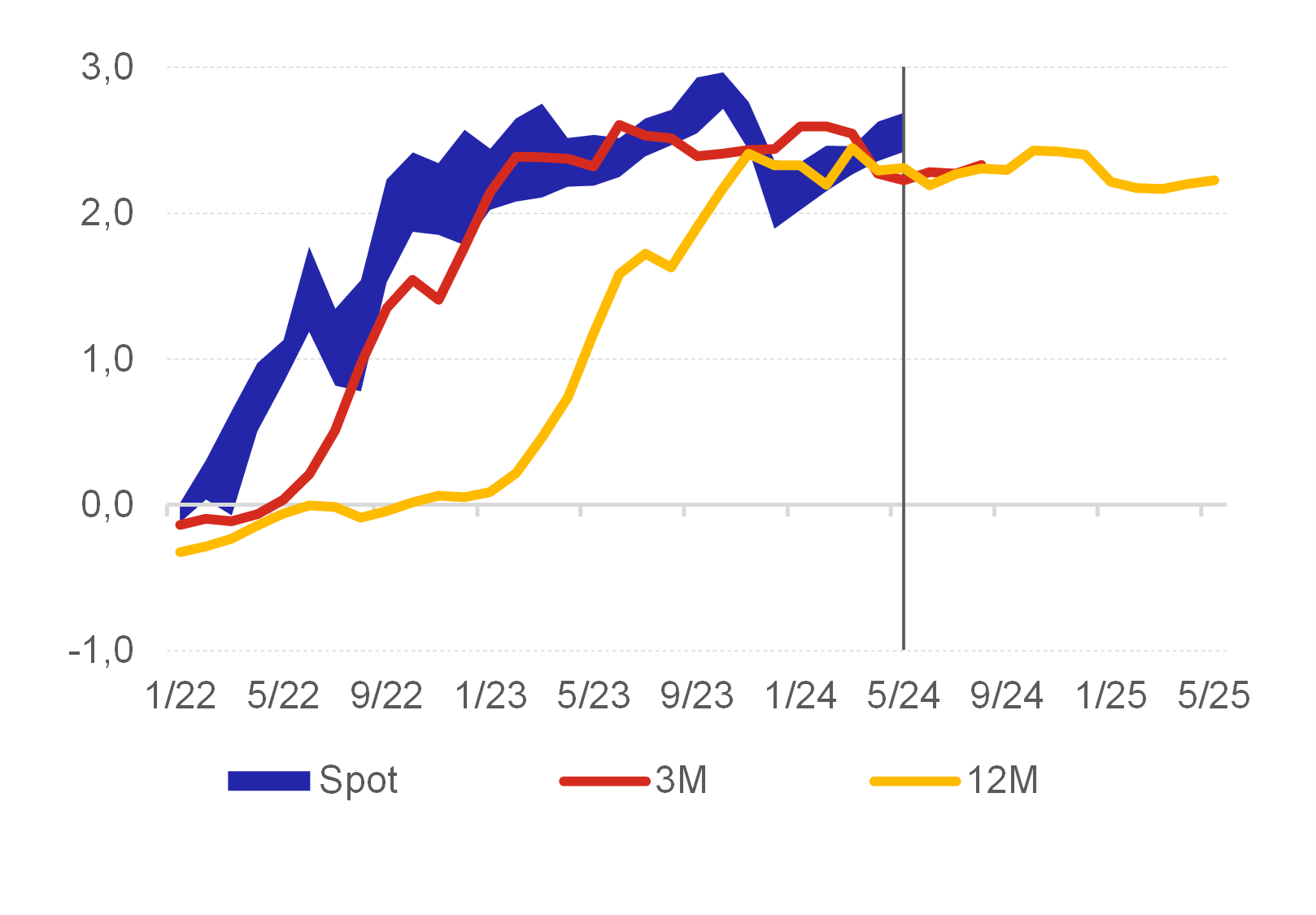

Chart 5 – Annual outlook for three-month interest rates in the USA and comparison with reality

(RMSE average)

Source: CF, Bloomberg

Note: The blue area denotes the range of the minimum and maximum price in the given month. The vertical line denotes the end of the observed data.

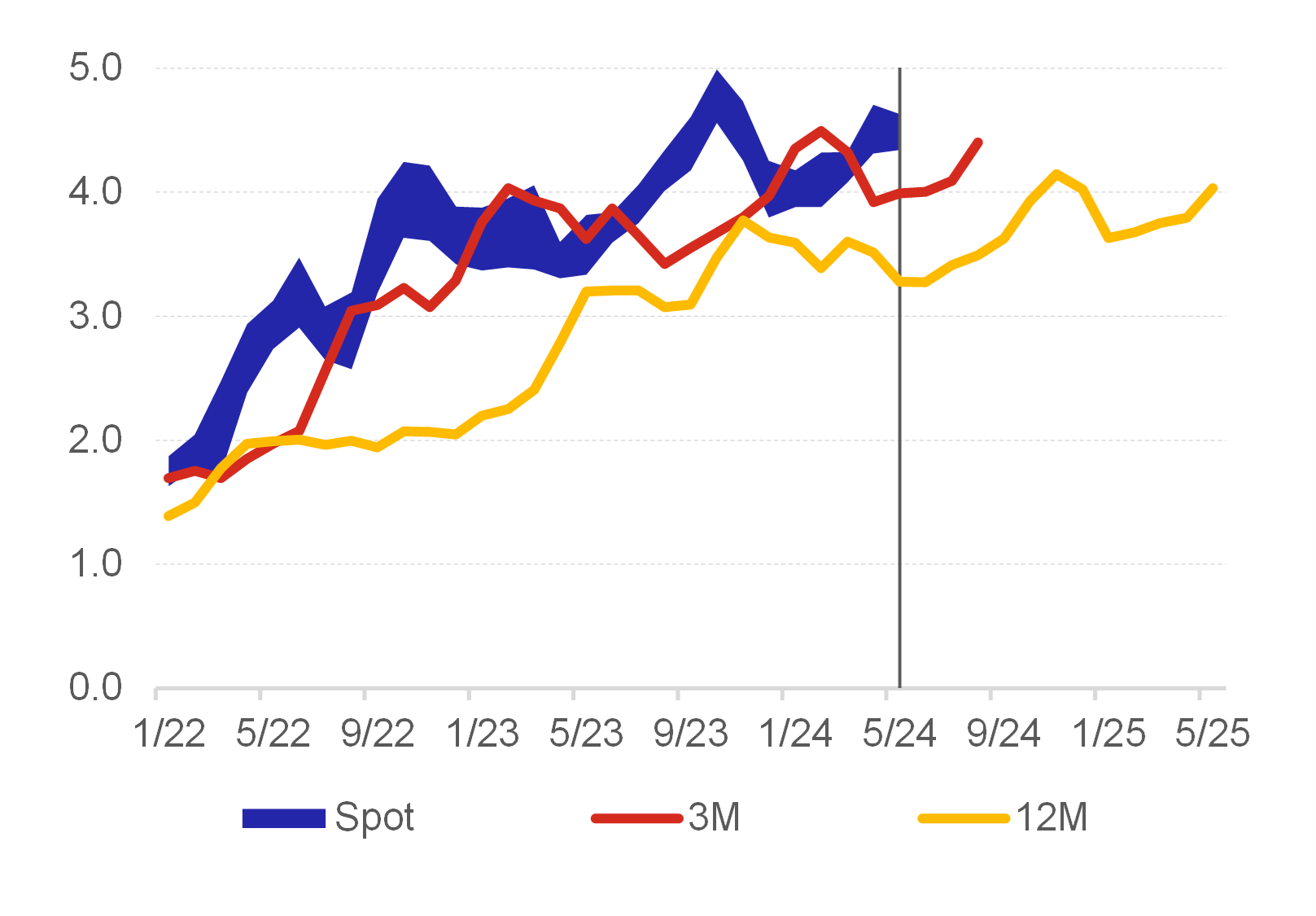

The outlook for government bond yields with longer maturities again shows a rather conservative approach, especially for the United States (Charts 6 and 7). Bond yields have been rising since the beginning of 2022, when it was clear that monetary policy would be tightened in both the euro area and the US economy. The CF analysts' short-term (three-month) outlooks for 10-year bond yields in the euro area were reliable last year, although they failed to capture the decline at the beginning of the year. The annual outlooks show a striking similarity to the short-term ones and have not so far been very reliable for last year. They have been stable for this year so far, but below the current value. However, the short-term outlooks for US government bond yields tended to follow current events and did not do very well last year. The outlooks for the one-year horizon were burdened by uncertainty and expectations of a rapid return by the rates to lower levels and at the same time expectations of a recession in the US economy, which did not happen last year. As a result, the one-year outlooks did not do well at all last year, expecting yields to be about 1 percentage point lower than they actually were.

Chart 6 – Outlook for 10Y German government bond yields and comparison with reality

(%)

Source: CF, Bloomberg

Note: The blue area denotes the range of the minimum and maximum yield in the given month. The vertical line denotes the end of the observed data.

Chart 7 – Outlook for 10Y US government bond yields and comparison with reality

(%)

Source: CF, Bloomberg

Note: The blue area denotes the range of the minimum and maximum yield in the given month. The vertical line denotes the end of the observed data.

Assessment of the accuracy of dollar exchange rate forecasts

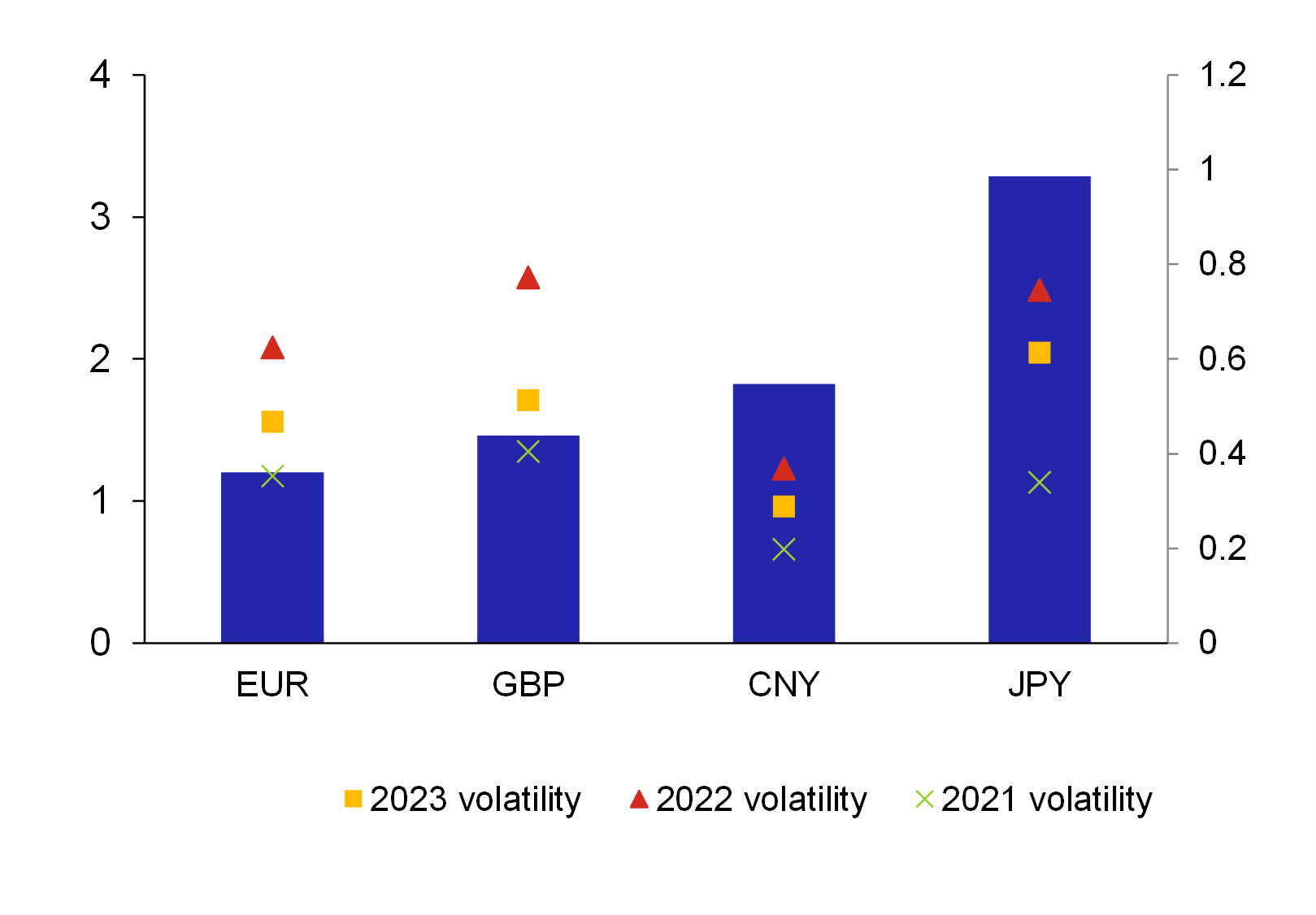

Last year, the exchange rates under review were more stable than in turbulent 2022 (Chart 8). GEO provides information on the outlooks for the exchange rates of selected currencies against the US dollar based on CF forecasts. For the euro and the Japanese yen and, since 2017, for the British pound, forward rates are also quoted based on covered interest rate parity and thus represent a current opportunity to hedge the future exchange rate rather than an outlook. We excluded the exchange rate of the Russian rouble from this year's assessment, as the exchange rate is fully market-based due to the Russian aggression in Ukraine. The accuracy of the CF outlooks and market contracts does not differ much, as illustrated by Chart 8, which shows their monthly development over the last more than three years.

Chart 8 – Forecast errors for the selected currencies’ exchange rates against the US dollar (three-month outlooks)

(MAPE; right-hand scale: volatility)

Source: CF, Bloomberg

Note: MAPE, volatility.

For all currency pairs, the euro exchange rate was most accurately predicted in both the three-month and one-year outlooks. By contrast, the Japanese yen forecasts fared worst, although for most of the past years the outlooks for the Japanese yen had been the best performers (Chart 8). The exchange rate of the Japanese yen also experienced great volatility last year, associated with the Fed’s tightening of monetary policy and the maintenance of the BoJ’s loose policy. The observed volatility of the currencies under review decreased significantly last year compared to 2022, yet still did not reach the pre-war level of 2021.

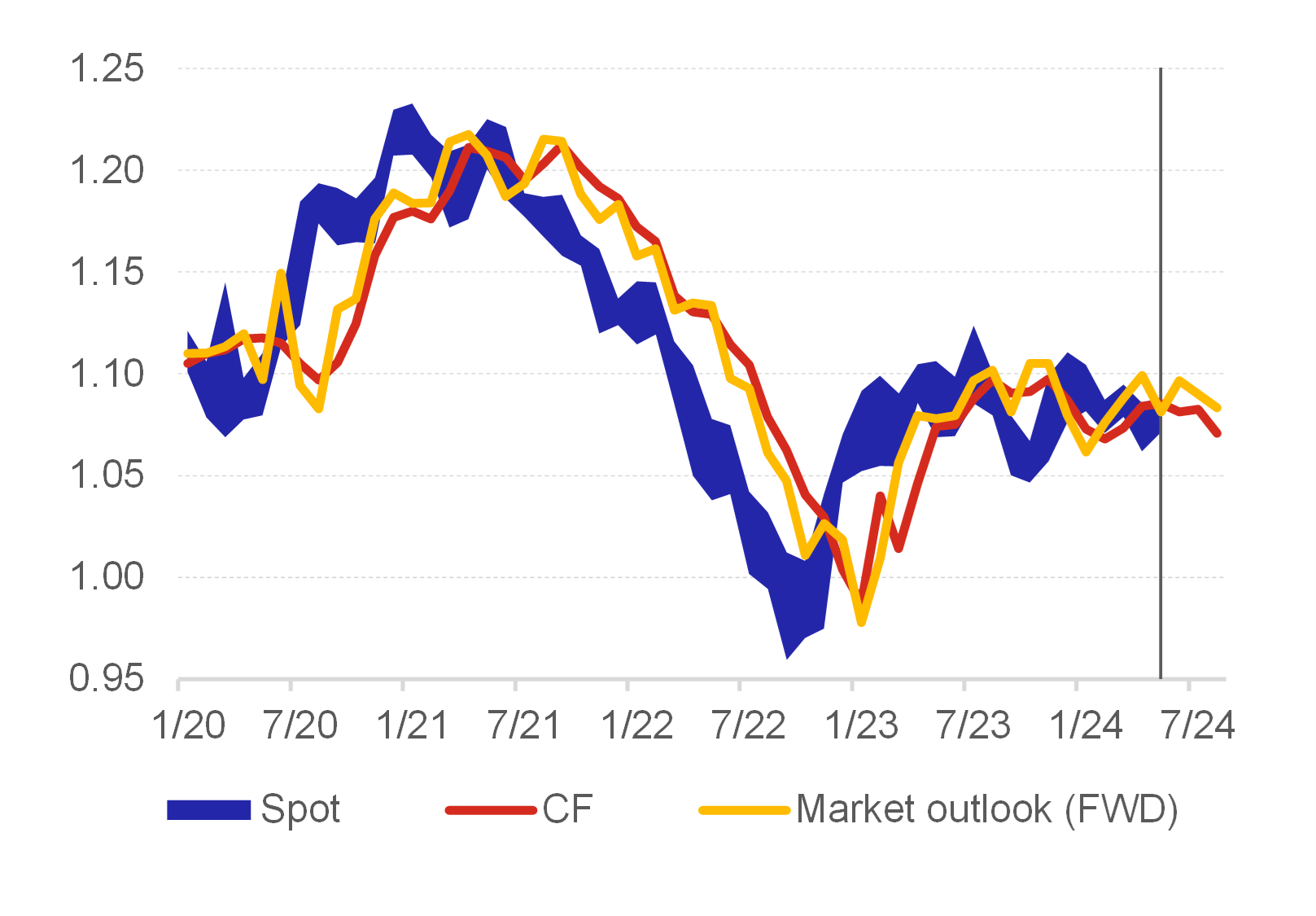

Overall, the three-month outlooks for the euro-dollar exchange rate were relatively closely aligned with observed reality and stable over the period under review. Chart 9 illustrates first the depreciation of the US dollar against the euro from the beginning of 2020, then its appreciation from the spring of 2021 to the end of 2022, and then the renewed appreciation of the euro. The US dollar has been maintaining a stable position vis-à-vis the euro since the start of last year, although the long-term outlooks consistently expect it to weaken. This is mainly due to the steady growth of the American economy and the tight monetary policy of the Fed.

Chart 9 – Three-month outlook for the euro-dollar exchange rate and the reality

(USDEUR)

Source: CF, Bloomberg

Note: The blue area denotes the range of the minimum and maximum price in the given month. The vertical line denotes the end of the observed data.

Assessment of the accuracy of Brent crude oil price forecasts

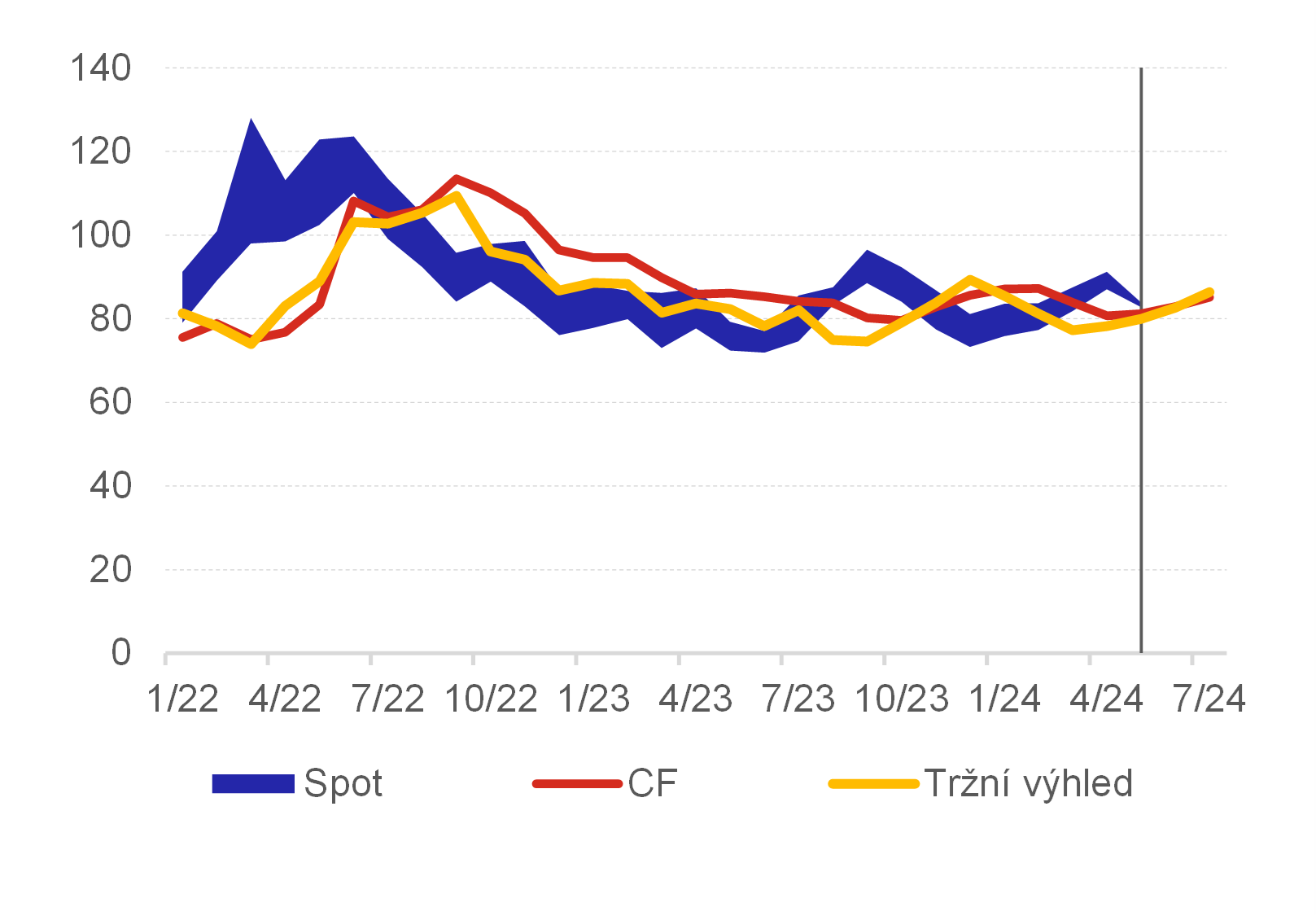

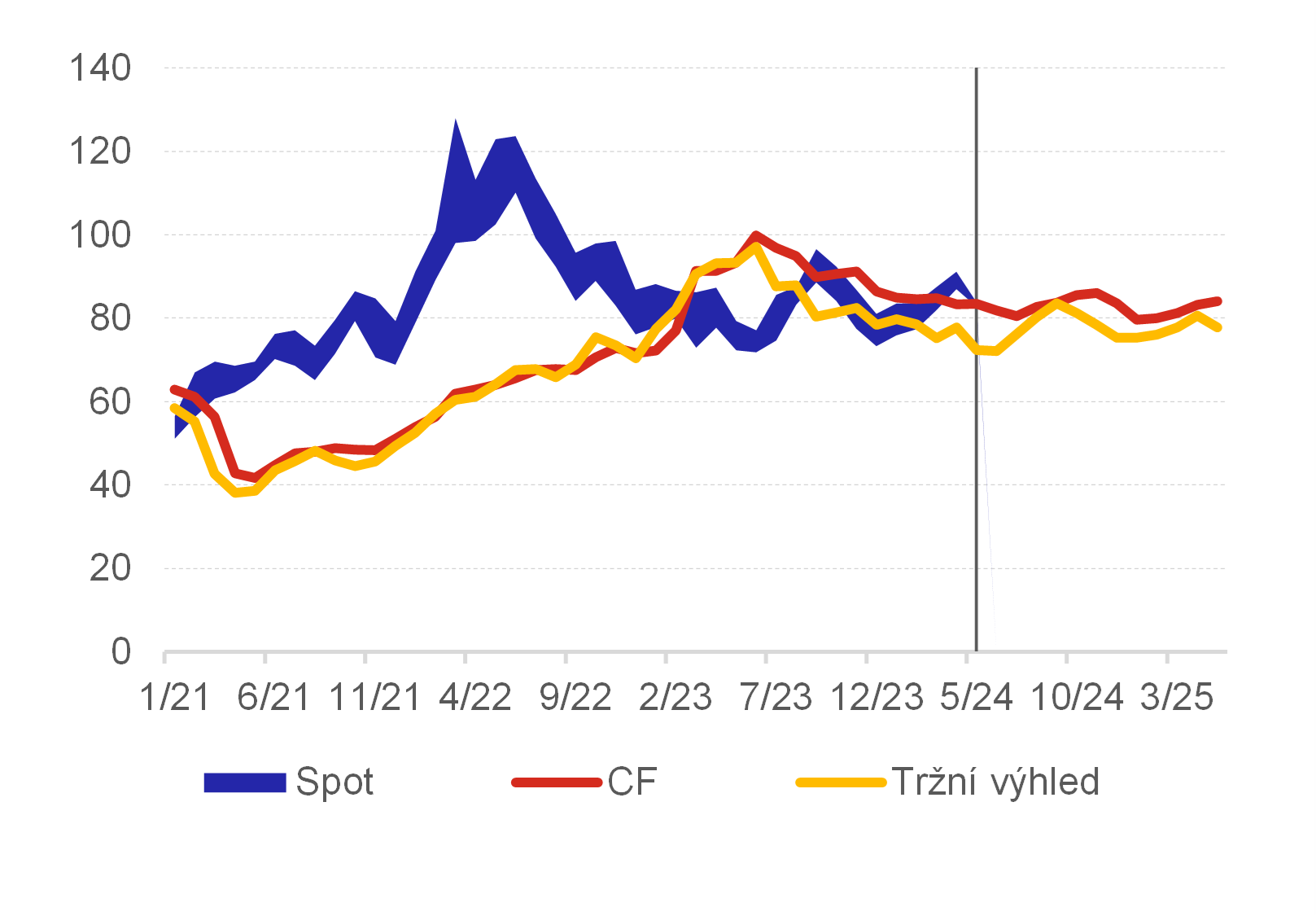

Of the commodity price outlooks that we provide in GEO, the price of Brent crude oil is one of the most important; the accuracy of its predictions through futures contracts and the CF was on average the same. Both sources of outlooks are regularly described in GEO, and it is clear from Charts 10 and 11 that the value and trend of the forecasts differ only slightly, although the market outlooks were lower last year and, at the same time, closer to the subsequently observed reality. The price of oil fluctuated close to USD 80 per barrel last year, and there was a significant fluctuation only in the autumn due to the conflict in the Middle East, with oil becoming more expensive, but this was followed by a reverse price correction. Of course, this situation could not be captured over a three-month or one-year horizon, and in this it was similar to the conflict in Ukraine in 2022. Naturally, the larger error was at the one-year horizon, where the 2022 expectations, i.e. from the time of the energy crisis, were incorporated into the outlooks throughout the year. In general, higher prices were expected by the CF analysts compared to market contracts last year. At present, the outlook is almost constant at around USD 85 a barrel in the short term, and just below USD 80 a barrel at the one-year horizon using market outlooks and just above USD 80 a barrel from the CF analysts.

Chart 10 – Three-month outlook for the Brent crude oil price

(USD/barrel)

Source: CF, Bloomberg

Note: The blue area denotes the range of the minimum and maximum price in the given month. The vertical line denotes the end of the observed data.

Chart 11 – One-year outlook for the Brent crude oil price

(USD/barrel)

Source: CF, Bloomberg

Note: The blue area denotes the range of the minimum and maximum price in the given month. The vertical line denotes the end of the observed data.

Conclusion

Last year saw a gradual normalisation after the significant unexpected external shock in the form of the start of the war in Ukraine in 2022. This significantly reshuffled the original estimates for GDP growth and inflation for 2023 in the countries under review. The subsequent energy crisis in Europe caused a sharp increase in previously unexpected inflation pressures and, to a lesser extent, led to a downward revision of GDP growth. Financial variables in particular were strongly affected by central banks’ changing monetary policy outlooks.

This article uses simple methods to assess the accuracy of the forecasts monitored in GEO over the past year. The accuracy of the forecasts from the institutions covered by GEO changes from year to year. This is one of the reasons why several institutions’ forecasts are monitored in the GEO. The accuracy of the CF forecasts has long been comparable with the available alternative forecasts, and this was also the case in 2023. The CF accuracy stems from their defining characteristic, namely that they are the simple average of the forecasts from the contributing private institutions.[2] The disadvantage, especially in turbulent times, is the slow reaction of predicted variables, which often “lag” behind market outlooks, as was the case last year, for example, with financial variables.

2023 was basically marked by a certain stabilisation for all the indicators evaluated. Last year saw not only the gradual fading of the energy crisis, but also the end of the monetary policy tightening cycle. From the point of view of economic developments, economies have adapted to new economic ties, the problems related to supply chains subsided, and there was a general stabilisation. The outlooks for macroeconomic fundamentals were gradually adjusted accordingly.

Authors: Filip Novotný and Petr Polák. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Czech National Bank.

Annexes

Annex 1 – Forecast errors for GDP growth for 2023

(percentage points)

Note: CF – Consensus Forecasts, IMF – International Monetary Fund, OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ECB – European Central Bank, Fed – United States Federal Reserve, BoE – Bank of England, BoJ – Bank of Japan, OE – Oxford Economics. MFE (mean forecast error) indicates the average forecast error for the given year.

Annex 2 – Forecast errors for consumer price inflation for 2023

(percentage points)

Note: CF – Consensus Forecasts, IMF – International Monetary Fund, OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ECB – European Central Bank, Fed – United States Federal Reserve, BoE – Bank of England, BoJ – Bank of Japan, OE – Oxford Economics. MFE (mean forecast error) indicates the average forecast error for the given year.

Keywords

forecast error, economic outlook, Consensus Forecasts

JEL Classification

E66, E27, C18

[1] Variability is measured in the analysis using standard deviation.

[2] The CF characteristics were discussed in more detail in an earlier article by Adam and Hošek ”How consensus has evolved in Consensus Forecasts” in the April 2015 issue of GEO.