Anticipated events versus surprise shocks in structural forecasting models: Czech National Bank’s practical perspective

Inflation targeting central banks must be forward-looking and thus use inflation forecasts to support monetary policy decision making. Central bank forecasts are commonly model-based and they need to incorporate all relevant information about future developments, i.e. future affairs. They are captured in forecasting model framework via anticipated future events or surprise shocks.

In general, future events in central bank forecasts, i.e. in structural forecasting models, can be treated as anticipated events or surprise (unanticipated) shocks. Surprises are not foreseen by economic agents until their realization. They appear out of the blue sky and the agents react to them only when they hit them. On the contrary, anticipated future events are foreseen in advance and thus all agents are able to accommodate effects of them in advance. In this case, nobody is surprised at the moment when the event eventually hits the economy. All agents have already adjusted their behavior and counted with the impact of the future occurrences.

Treating future events as anticipated information should be the natural choice for central bank forecasts. There are at least two reasons. First, central bank forecasts should encompass all available information. Communicating their forecasts, central banks make economic agents anticipate the future events. Treating these events as surprises would be false in such a case and it might lead to policy errors. Second, without anticipated news, inflation forecasts might not reach the target within the policy horizon and thus would not anchor inflation expectations. When treating an event as a surprise shock, there is a response to it only at the time of its realization, including the response of the central bank. However, this may be too late to bring inflation back to the target due to transmission lags. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the surprise shocks should not be used at all, but rather rarely; for example, if future events are highly unlikely or contingent on further steps to be taken in the future.

Although using anticipated events has a number of advantages, they also have drawbacks and thus various modifications are researched and practically applied. Full information about future events is often considered as unrealistic and leads to a ‘forward guidance puzzle’ in structural forecasting models. This means that implied monetary policy reactions to anticipated future events are stronger the further in the future these events are to occur. In some cases, the initial response to the expected event might even be opposite compared to the unanticipated version of the same event or implying quite high volatility in optimal behavior. These are usually challenging to explain. Additionally, agents’ responses to expected news vary with the foreseen horizon - not only the size of the shock, but also the length of the horizon matter, see Figure 1. This presents an issue in consecutive forecasts, where the distance of the impact of an anticipated future events from the beginning of the forecast horizon differs. Instead of simply moving along the initial trajectory of the response to the event, the response varies with the forecast horizon changes.

Figure 1: Impulse Responses to Expected Foreign Inflation Move (Deviations from Steady State Values). Note: The 12Q ahead expected event in blue and 8Q ahead in green line. The event as unanticipated surprise in red.

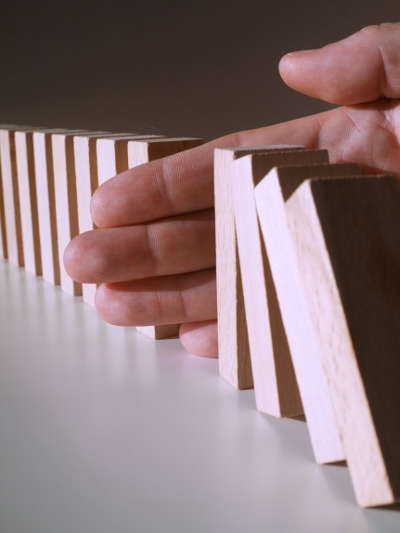

Relying on anticipated future news, the Czech National Bank uses a forecasting framework based on the Limited Information Rational Expectations (LIRE) concept, which mitigates possible related drawbacks. Under the LIRE concept, information about expected future events enters the agents’ information set in a controlled manner. The full forward-lookingness is thus limited to only several quarters ahead and the information about more distant events is discounted. Near events are taken into account of agents’ decision-making at present fully while the very distant ones are neglected. As the foreseen window moves along the forecast trajectory, corresponding in turn respectively to each quarter, the distant events are gradually taken into account. One can imagine the LIRE concept as driving a car under foggy conditions. The driver does not have the full path figured out from the start, but learns about the road ahead as soon as it emerges from the fog in front of the car.

The LIRE approach is valuable especially in the recent situation of extraordinary pandemic and macroeconomic development, when the distant future is highly unclear. In general, the approach handles the problem of limited impact of future events on the current decisions, low availability and especially poor reliability of some distant outlooks, and high dispersion of long-run projections about the future events. This simply means that highly uncertain news in the distant future do not strongly (or not at all) affect the current macroeoconomic behavior nor the monetary policy response. Nevertheless, it becomes relevant later on and the monetary policy will react to it when it gets close enough.

We believe that the LIRE approach reflects the reality nicely. This novel concept keeps the Czech National Bank among the world modeling and analytical leaders. It is practically and successfully used in the Czech National Bank’s monetary policy analytical and forecasting system, where it helps to deliver intuitive results for several years. To shed more light on this area, read our related paper CNB RPN 2/2021.