Cross-border payments at a crossroads between SWIFT and DLT

Decentralized ledger technologies (DLT) made popular by bitcoin and other crypto assets did not create new moneys. One of the things they did create was an alternative channel of cross-border value transfers independent of correspondent banks. In response, banks engaged in international payments started to experiment with blockchains themselves. In this article, I review the current cross-border payment landscape from the point of view of DLT adoption and try to assess the potential of current and emerging solutions.

Published in Global Economic Outlook – June 2023 (pdf, 1 MB)

Introduction

The economic importance of cross-border payments is growing steadily hand in hand with the increasing international mobility of goods, services, capital and people. Factors such as expanding GVC, international trade and e-commerce, cross-border asset management and global investment flows are behind this growth, as are international remittances sent by migrants. Remittances in particular play a vital role in low and middle-income economies and in some cases make up an indispensable source of development finance.

Whereas in recent years domestic payments have improved in terms of speed, safety, transparency and cost-efficiency, with many more initiatives on the way, cross-border payments are generally considered lagging behind domestic ones in each of these respects. In some instances, a cross-border payment can take several days and cost up to 10 times more than a domestic payment. Accordingly, demand for cross-border payment services that are as efficient and safe as domestic ones is increasing steadily. Bank transfers and card payments have been the most widespread methods of transferring funds across borders for dozens of years. In recent years, mobile payments have started to compete with these two methods (M-PESA in East Africa is a good example), with their providers promising customers higher speed and lower cost of delivery. These properties are in especially high demand in those parts of the world in which the speed of innovation of traditional cross-border payment technologies is lowest.

Chart 1 – Growth in the number of fast transactions in TARGET2, 2008-14

(%)

Source: Craig et al. (2018)

Note: Daily fraction of interbank & customer payments settled within 5 minutes.

Cross-border payments are by definition more complex than purely domestic ones, since national payment systems are operated by sovereign monetary authorities. Transfers of funds between two jurisdictions can take place because international banks provide accounts for, and have their own accounts with, foreign counterparts. A foreign currency payment is executed when an account in one currency is credited in one jurisdiction and another account in another currency is debited with the corresponding amount in another jurisdiction. When the payer’s and payee’s banks do not have a direct relationship, they need to engage a “correspondent” bank to act as an intermediary. The latter provides accounts for both banks. Other payment providers such as money transfer agents and fintechs also use this interbank network as an intermediary in the provision of payment services to businesses and individuals. This correspondent banking model is both an essential component of the traditional global payment system and, at the same time, the host of most existing frictions. The latter refers to multiple intermediaries, time zones, jurisdictions and regulations. Given that rules regarding capital flow management and/or controls, requests for documentation, balance of payments reporting, and other compliance procedures differ from country to country, significant payment delays are a fact of life, especially in EMDE. Other frictions accompanying cross-border payments include fragmented and truncated data formats, different operating hours, high funding costs (including “trapped liquidity”, particularly in cases of large time-zone differences), legacy technology platforms, long transaction chains and weak competition.

Challenges to the established payment landscape

At the beginning of the millennium, there was essentially no alternative to the correspondent banking model for international transactions. The global correspondent bank network comprised the major multinational bank (MNB) groups. These MNB wielded overwhelming market power, which is why using their services was quite expensive. In addition, there was very little sign of technological progress, especially in terms of speed (see Chart 1). Founded in 1973, the Society of Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) operates the largest existing inter-bank messaging service and has hence been the backbone of the correspondent banking model ever since. Smaller networks with a specific scope (CHIPS, CIPS, SPFS and others) have adopted the same messaging format as SWIFT (including the incoming ISO 20022), as well as other attributes. On the other hand, remittances, particularly involving EMDE clients, were often in the hands of non-bank intermediaries, which were insufficiently regulated and, at times, had even lower transparency of operations than correspondent banks. The fees were also high and volatile.

Crypto assets have been gaining ground globally since 2010. As opposed to the original proclamations, they did not signify the emergence of decentralized money, but did – at least on the fringe – provide an alternative to correspondent banking in the retail payments domain. In principle, every functional cryptocurrency can act as a cross-border remittance vehicle. It is enough to buy crypto for fiat at the payer’s end, transfer it and let the payee conduct the back-conversion on the receiving end. The crypto leg of such a transaction in many networks takes just seconds to complete and is relatively cheap. Naturally, moving cross-border payments “on-chain” is much easier said than done, given that the associated technical demands, access costs and user risks for the parties involved are not insignificant. Although there are banks willing to take over those risks on behalf of their clients, there are far-reaching compliance implications for legitimate intermediaries, which implies additional fee components for users. However, the main obstacle to a full-scale crypto disruption of the cross-border payment landscape, besides security and regulatory concerns, has been price volatility.

The response to prohibitive crypto price fluctuations was the creation of stablecoins, advertised as a solution to the volatility risk on the user side. In truth, the risk was simply shifted to the stablecoin issuer, relegating it to a more opaque environment of coin operators and creating an additional source of risk tied to credibility, not very different from traditional commercial banking (Hertig, 2023; Derviz, 2020).

The Libra announcement in 2019 suggested – at least from the two billion-strong FB-user perspective – a resolution of the stablecoin credibility issue. The joint strength of the original Libra Association membership created a vision of an institution with virtually unlimited resources behind the envisaged payment instrument. Holders of Libra wallets, it seemed, would no longer experience any of the traditional barriers to international value transfers (compliance, credibility, security, excessive exchange rate fluctuations) as long as they stayed in the network. However, Libra’s business concept was fuzzy from the outset and did not become much clearer in the years to follow or under Diem, its new name, either. The eventual abandonment of the project came as no surprise to anybody with an idea about the fundamental differences between BigTech and Big Finance (Financial Times, 2022). The principal consequence of the initiative was, as is often the case, unintended.

After the Libra announcement, major central banks, governments and international standard-setting bodies became seriously concerned about the erosion of their powers. (“Monetary policy implementation issues” were officially cited.) The threat looked a lot more real and present when coming from a stablecoin potentially used by 1.6 billion active Facebook account holders than from bitcoin and other crypto toys intended for a relatively narrow circle of true believers. The response came in the form of a rekindling of various hitherto slumbering CBDC (Central Bank Digital Currency) projects. Although the prime reason for CBDCs was to defend monetary sovereignty in the new world of private digital assets, the facilitation of payments, both domestic and cross-border, was listed among the official priorities.

Frictions and remedies

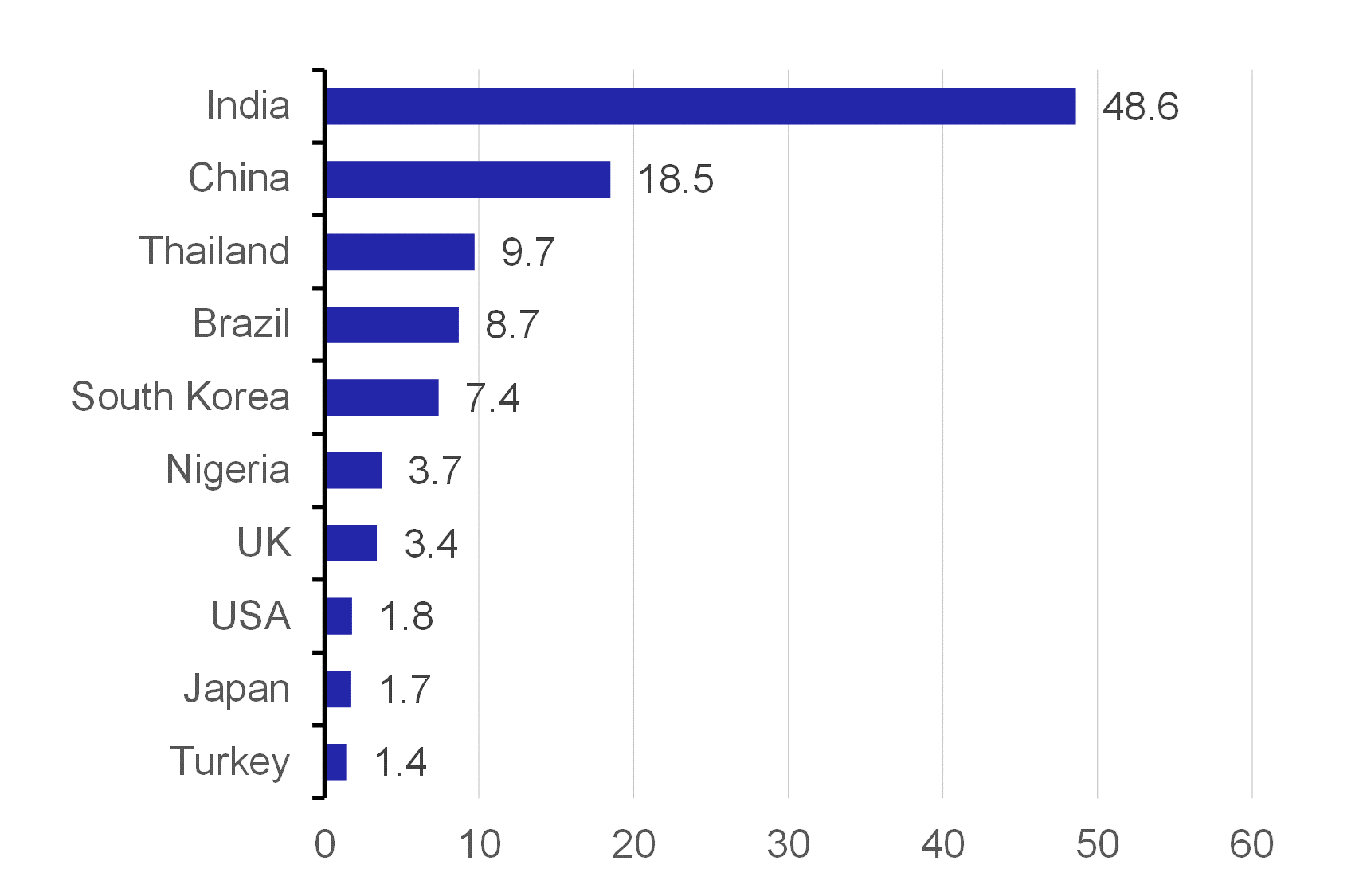

Although the aforementioned frictions are ubiquitous in the cross-border payments domain, several of them, such as those related to technology, the length of the intermediary chains, and the oligopolistic market structure, are perceived as particularly severe in the remittance segment. This explains the differences in perspective of developed and EMDE countries with regard to priority areas that require improvement: EMDE countries would benefit the most if access to remittances becomes cheaper and easier. This is why these countries are most eager to embrace any technology that promises instant payments (see Chart 2). This is also the reason why the typical blockchain-developing (Ripple, Stellar) and other fintech enterprises that are waging inroads into the cross-border remittance domain (MobiFin, Flywire, Remitly, Wise) are primarily targeting clients in EMDE.

Chart 2 – Adoption of fast payments in selected countries

(number of transactions in billions)

Source: ACI Worldwide.

Note: Top 10 countries, ranked by real-time payments transactions, 2021.

The EMDE perspective has made a distinct imprint on the ongoing inter-government efforts to improve cross-border payments. In 2020, the G20 declared improving cross-border payments a priority. Its justification was that it clearly reflects the remittance tribulations of the developing world. The Financial Stability Board (FSB), in conjunction with the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and other standard-setting bodies, were asked to co-ordinate a cross-border payments enhancement programme (FSB, 2022). The programme was divided into three stages: Assessment, Building Blocks and Roadmap. There are currently 19 “building blocks”, as defined by CPMI. These were grouped into five focus areas: (i) commiting to a joint public and private sector vision to enhance cross-border payments (ii) coordinating regulatory, supervisory and oversight frameworks (iii) improving existing payment infrastructures and arrangements to support the requirements of the cross-border payments market (iv) increasing data quality and straight-through processing by enhancing data and market practices, and (v) exploring the potential role of new payment infrastructures and arrangements.

In the meantime, pressure from decentralised networks have had a visible effect on SWIFT, the superstructure which once enjoyed undivided dominance in the international payments domain. The company’s response to the demands of faster user-friendly payment improvements was the widely publicised SWIFT gpi (Global Payments Innovation), launched in 2017 and currently linking over 4,200 banks in more than 150 countries[1]. Its recent acceleration, which could reportedly have been carried out a long time ago but was not recognised as a priority until the fintech (and DLT) incursion into the international payment business began, has so far been the most apparent effect of blockchain proliferation on international payments. In general, for various reasons, SWIFT is not always a front-runner in terms of implementing innovative standards. Notably, the ISO 20022 messaging standard for cross-border payments, which is currently being implemented worldwide, was adopted ahead of SWIFT by smaller services, such as CIPS in China.

Importantly, in its effort to make cross-border payments faster and less expensive, SWIFT gpi does not rely on DLT. Instead, it uses cloud-based tools to improve the existing processing and messaging infrastructure. Crucially, it is upgrading its messaging service to enable real time start-to-end transaction tracking by participating parties, making the time lags and other obstacles in the payment process clearly attributable to a particular participant. Since then, it has been reported that the typical cross-border remittance time required by some banks handling this business in EMDE has miraculously shortened from several days to several hours, in many cases to less than an hour. However, whereas SWIFT gpi has reduced the already decent transfer times in advanced countries to a new minimum of several minutes, same-day transactions are still a problem in many EMDEs. It turns out the main delay factors are on the receiving end, i.e. the payee’s bank: both external (compliance requirements, especially in the case of substantial capital controls) and internal (the bank’s own operational frictions) that no amount of technical upgrade seems able to eliminate (BIS, 2022a).

SWIFT is also adapting to the possibility of a mass DLT incursion in other ways, even though it has not yet proceeded beyond the proof-of-concept phase. For example, it has launched a trial to interlink domestic CBDCs to enable cross-border payments in them. Again, its approach is to transform rather than disrupt, insofar as it intends to offer CBDC-issuers the possibility of sending messages rather than money. On the contrary, blockchain payments advertise the integration of the message with the movement of value, as well as the ability to execute atomic transactions.

In recent years, many central banks have sought to establish cross-border interoperability in the course of their CBDC experiments. CBDCs base their aspiration to ease cross-border payments on the ability to solve the intermediary problem inherent in the correspondent banking model. However, the solution (the multiple-CBDC or mCBDC construction) will require interlinking CBDC systems, which implies common international standards, harmonised clearing mechanisms and, eventually, a common technical interface and a single multilateral payment platform, possibly with a special unit of account (and a native asset representing it). No matter how enticing the vision of associated benefits may be, achieving such interoperability is a highly ambitious enterprise because of different regulatory frameworks across jurisdictions.

More generally, many central bankers experimenting with CBDCs give the impression that they are living under the illusion that the rules of access and use they eventually decide upon will be obeyed by the public without objections. The rules themselves, though, particularly those concerning access by non-residents, conversion and the relationship to the existing forex, have not been made clear yet (BIS, 2021, 2022b). There is even less clarity in the area of legal and regulatory CBDC integration across jurisdictions (Zetsche et al. 2022). In short, an end-user is currently faced with the dual perspective of easy (albeit risky and legally unprotected) access to multiple permissionless blockchains allowing for global value transfers without checks or limits, and the uncertain outlook of a CBDC-based permissioned DLT with a solid degree of legal certainty, although associated with numerous jumps through bureaucratic hoops held up by domestic monetary and regulatory authorities. Even a tentative form of these jumps remains difficult to predict at the current juncture. If supervised access to mCBDC proves to be less digestible than the free wilderness of permissionless DLT, the whole vision of internationally integrated retail CBDCs may hit a wall of disinterest at the same time as more and more retail customers, dissatisfied with legacy international payment models, migrate to private crypto solutions. As can be expected, the projects involving cross-border interoperability of wholesale CBDCs, i.e. the option which is only indirectly significant to remittance facilitation, are momentarily the closest to operational mCBDC pilots. Regulated financial institutions are much more easily “convinced” to participate in such pilots than private individuals.

Concurrently, efforts to improve cross-border payments have been developed in the private sector. Examples of corporate DLT payment initiatives include RippleNet, Stellar, Partior, Fnality, etc. The latter two are examples of solutions by bank consortiums employing permissionless blockchains either fully or at least partially. The motivation of the banks is different to that of the official sector and the retail segment: faced with the ongoing encroachment of DLT in the payments domain, they need to be prepared for a period of uncertain duration when multiple technologies, institutions and standards will compete for market dominance, and familiarise themselves with coming alternatives in advance.

Partior is, by its own definition, a “blockchain-powered platform for value exchange”, that is, an interbank DLT-based network. It supports multi-currency payments starting with the US dollar and Singapore dollar, with six more currencies (GBP, EUR, AUD, JPY, CNH and HKD) currently onboarding. It was launched in 2021 by JP Morgan, DBS Bank, and Temasek (Ledgerinsights, 2022). While Partior is a wholesale network, it also welcomes entrants that add retail payment applications on top. Payments are in commercial bank money (M1). In the future, Partior intends also to support central bank money (M0), giving M0 a clearing function across settlement banks, whereas M1 is given a clearing function within the commercial bank ecosystem.

Partior’s inception is actually related to an mCBDC experiment: Project Ubin run by the Monetary Authority of Singapore and the Bank of Canada. It is currently involved in Project Dunbar, the mCBDC project with the central banks of Singapore, Malaysia, Australia and South Africa and the BIS Innovation Hub. Partior may also participate in another BIS Innovation Hub initiative, Project Meridian, which aims to synchronise RTGS infrastructures with digital asset ledgers and payment systems in various currencies. So, the potential of central banks to have nodes on Partior clearly exists.

Partior positions itself as a network rather than a payment or settlement system. It cannot itself initiate a transaction, move, store money, or create finality, and it does not collect any data. Banks have nodes on the network to make payments, implying they bear responsibility for themselves. Accordingly, Partior does not need a central bank approval, which enables it to expand quickly. The participant banks own the smart contracts, have control over their deployment, initiate payments and determine finality. Still, commercial banks may need to get the green light from their regulator to use the network.

Fnality, formerly known as the Utility Settlement Coin, is the interbank payment and settlement platform that uses blockchain technology and is now backed by 17 major financial institutions. Whereas Partior works with commercial bank money transfers, Fnality payments are all backed by central bank money, making its token a synthetic CBDC. This significantly reduces counterparty risk. Fnality tokenises money deposited at a central bank to enable the settlement of DLT-based transactions with on-chain digital currency. The planned fiat currencies to be involved are the British Pound, euro, US dollar, Japanese yen and Canadian dollar. The Fnality investors from the financial sector are Banco Santander, Bank of New York Mellon, Barclays, CIBC, Commerzbank, Credit Suisse, Euroclear, ING, KBC Group, Lloyds Banking Group, Mizuho, MUFG Group, Nasdaq, Nomura, SMBC, State Street and UBS. Although already designated a systemic payment system by the UK Treasury, its launch was delayed in September 2022 by nine months due to an ongoing probe by the Bank of England.

Conclusion: DLT as a catalyst, not a wrecking ball

Blockchains were invented as a technology for trustless value exchange, and hence they are usually demanded in cross-border payments when confidence-building prior to actual trade is complicated or impractical. This means above all new products, new markets and immature or compromised institutions. Therefore, it should not be a surprise if remittance solutions on permissionless blockchains remain a much sought-after alternative in jurisdictions where pressure on institutional quality improvement has not so far borne the desired fruit. Characteristic of this state of affairs, Ripple is already a household name on the Indian subcontinent, while still being a fairly unknown entity outside expert circles in the West.

At the same time, DLT payment initiatives have neither destroyed nor replaced the correspondent banking model of cross-border payments between well-established counterparties in a legally stable environment. They do, however, exercise pressure on incumbent players and legacy technologies to seek faster avenues of improvement. As a side effect, they may incite the creation of some really widespread and popular global stablecoins acting as units of account in partial interbank decentralised payment networks, until one (or a few) dominant technology(ies) force the rest to adapt to a universal standard. Nevertheless, none of this is a real threat to the monetary sovereignty of nations or the regulatory powers of central banks, since any international payment system, regardless of technology, needs capital and liquidity coming from fiat moneys and their issuers.

Adding CBDCs to the mix of payment opportunities is not essential, even though this can, under certain circumstances, facilitate policy implementation (as, for example, in sanctions enforcement). On the home front, CBDCs remain “a solution in search of a problem” (Waller, 2021). But, if they are mainly useful for international transactions, their potential depends crucially on the central banks’ ability to drastically expand monetary bases. The existing multi-CBDC initiatives offer settlement in M0 (after all, CBDCs are themselves M0). A good example is mBridge (BIS, 2022b). Scaling up such systems in line with private sector demand is difficult, not just technically, but also in terms of accommodating independent monetary policy and the macroprudential objectives of participating jurisdictions. Central banks would have to accept a higher degree of monetary policy coordination than they were used to. Another potentially explosive issue, i.e. that of pending FX trade implications, has not been seriously addressed at all thus far. For instance, an mCBDC native asset would offer a new category of triangle arbitrage trades on formerly unavailable media to a wide range of participants with likely consequences in the form of large liquidity swings across market segments, in extreme cases, even a dry-up of trade in certain fiat currencies (Benigno et al., 2022).

At present, payment solutions based on interoperable CBDCs look like a fairly expensive safeguard designed for exceptional circumstances. That is, even in the hypothetical case where the whole M0 were tokenised and transformed into CBDC, only a fraction of international transactions could be serviced. For instance, the current daily transaction volume handled by SWIFT alone is sometimes claimed to be around USD 15 trillion, i.e. more than the monetary bases of the USA, the euro area and China combined. Regardless of the reliability of these estimates, it is unlikely that any multi-CBDC could aspire to service the overall demand for cross-border transactions without a far-reaching change in the balance sheet composition and, more importantly, the scope of the activities of the central banks involved. An economic rationale for such a change has not been offered so far. In practice, cross-border payments will always need M1 and transnational commercial bank networking. Here, DLT can incite transformation, but not necessarily become the dominant element, since, as history shows, high-trust institutions are usually cheaper and more efficient.

Autor: Alexis Derviz. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Czech National Bank. All errors and omissions are the author’s responsibility.

References

Benigno, P., L. Schilling, and H. Uhlig (2022) Cryptocurrencies, currency competition, and the impossible trinity. Journal of International Economics 136 (C); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2022.103601.

BIS (2021) Central bank digital currencies for cross-border payments. Report to the G20 (July).

BIS (2022a) SWIFT gpi data indicate drivers of fast cross-border payments. Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (6 February) https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/swift_gpi.htm .

BIS (2022b) Project mBridge: Connecting economies through CBDC. BIS Innovation Hub Report (October); https://www.bis.org/about/bisih/topics/cbdc/mcbdc_bridge.htm .

Craig, B., D. Salakhova, and M. Saldias (2018) Payments delay: propagation and punishment. Banque de France, Working Paper Series no. 671 (April), https://publications.banque-france.fr/en/payments-delay-propagation-and-punishment .

Derviz (2020) Stablecoins: – a gateway between conventional and crypto financial universes? Czech National Bank GEO (March) 12-16. https://www.cnb.cz/export/sites/cnb/en/monetary-policy/.galleries/geo/geo_2020/gev_2020_03_en.pdf .

Financial Times (2022) Facebook Libra: the inside story of how the company’s cryptocurrency dream died (March 10), https://www.ft.com/content/a88fb591-72d5-4b6b-bb5d-223adfb893f3 .

Hertig, A. (2023) What is a stablecoin? https://www.coindesk.com/learn/what-is-a-stablecoin/

FSB (2022) G20 Roadmap for enhancing cross-border payments. Consolidated progress report for 2022 (October); https://www.fsb.org/2022/10/g20-roadmap-for-enhancing-cross-border-payments-consolidated-progress-report-for-2022/ .

Ledgerinsights (2022) https://www.ledgerinsights.com/partior-jp-morgan-dbs-blockchain-payments/ (November).

Waller, Ch. J. (2021) CBDC - A solution in search of a problem? Speech at the American Enterprise Institute, Washington DC, 5 August 2021; https://www.bis.org/review/r210806a.htm .

Zetzsche, D., L. Anker-Sørensen, M. Passador, and A. Wehrli (2022) DLT-based enhancement of cross-border payment efficiency – a legal and regulatory perspective. BIS WP No. 1015 (May).

Keywords

DLT, blockchain, cross-border payments

JEL Classification

E58, F31, F41

[1] See https://currencywave.com/what-is-swift-gpi/, or https://www.swift.com/our-solutions/swift-gpi/about-swift-gpi/join-payment-innovation-leaders and https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/swift_gpi.pdf