ECB and financial markets: not always on the same wavelength

The ECB cut its interest rates for the first time since the pandemic in June. This step was largely expected by financial markets. However, at the start of 2024, financial markets were still expecting the ECB to take this step in April and to continue the commenced rate cuts at a strong pace until the end of the year. The market outlook for the main interest rate, derived from implied market rates, thus deviated appreciably from the ECB’s official communication regarding its future monetary policy.[1] In this article, we will examine the circumstances that may be behind such a situation. Our analysis indicates that financial markets, when predicting the ECB’s monetary policy steps, try to anticipate “tail-risk” scenarios in which the ECB could be surprised by economic trends in the euro area, which could lead to a subsequent rapid and substantial monetary policy adjustment. A key moment for the divergence of views seems to be a situation where new data do not support the ECB’s outlook–especially the short-term outlook. Financial markets respond quickly to current economic data. Unlike the ECB, they revise their outlook immediately after new data are released and may place an excessive emphasis on negative news. However, this approach was also supported by the communications of the ECB’s Governing Council, which, in particular over the past two years, has emphasised the importance of current data in its decision-making process.

Published in Central bank monitoring – June 2024 (pdf, 837 kB)

Monetary policy surprises or how financial markets guess what central banks will do

Financial markets cannot always predict what a central bank will do and may be surprised by a change in monetary policy. For example, an IMF study (IMF, 2002) confirmed that financial markets were not able to correctly predict the ECB’s interest rate decisions, especially in the case of significant interest rate movements. The surprise in monetary policy, i.e. the market response to unexpected central bank actions, has gradually gained great attention in literature. Various studies highlight various reasons for their creation or strength – financial market uncertainty, monetary policy uncertainty and central banks’ credibility and communication. Sekandary and Bask (2023), for example, examined the effects of monetary policy surprises on stock returns at various levels of monetary policy uncertainty, identifying a more pronounced negative impact in the event of higher uncertainty. Oliveira and Simon (2023) focused on the role of a central bank’s credibility in interpreting monetary policy surprises. According to their results, high credibility leads to lower inflation expectations, while low credibility conversely leads to increased expectations. Benchimol et al. (2023) showed that financial uncertainty amplifies the stock market’s response to monetary policy surprises, with a stronger impact on shocks towards monetary policy easing. Finally, Gapen and Krane (2021) found that monetary policy surprises increased stock market volatility, especially in periods of high economic uncertainty, suggesting that central banks need to take prevailing market conditions into account in their policy actions. Kaminska et al. (2023) documented the impact of monetary policy surprises on term premiums and hence on the structure of interest rates. Monetary policy surprises therefore play an important role in the transmission of monetary policy and are closely monitored by central banks.

According to the latest literature, monetary policy surprises are also linked to information on the state of the economy. In this interpretation, monetary policy surprises can be a purely monetary policy shock, but they can also contain information shocks. In Jarociński and Karadi (2020), information shocks are unexpected parts of monetary policy announcements that provide new information on economic fundamentals, not just indications of changes in the policy stance. Such shocks occur when a central bank’s announcement reveals information about the state of the economy that was previously unknown to the market. For example, an announcement that includes an unexpected increase in interest rates may be interpreted not only as a tightening of monetary policy, but also as a signal that the central bank has new information about inflationary pressures or economic growth. The study emphasises that such information shocks differ from purely monetary policy shocks, which are unexpected changes in interest rates or other policy tools that do not provide new information on economic fundamentals. A proper distinction between these types of shocks is key to understanding the actual impact of monetary policy announcements on financial markets and the wider economy.

Studies focusing explicitly on different opinions of financial markets and central banks are currently lacking in the literature to a greater extent. One exception is Sastry (2022), according to which the gap is due to a disagreement between markets and a central bank regarding the accuracy of public data (asymmetric confidence in data). Markets are also more pessimistic in the event of an economic downturn and tend to overestimate trends in interest rates (meaning a decline here). A slightly different approach, but with the same message, can be found in Sinha et al. (2023). The paper examines the dispersion of expectations regarding future trends in the base rate, pointing to different macroeconomic outlooks for participants as the main factor behind the widening of this dispersion. The hypothesis that market participants implicitly rely on different perceptions of the central bank’s reactions as defined by the variable Taylor rules has not been confirmed in empirical analyses.

However, information shocks, defined in Jarociński and Karadi (2020), can also be interpreted as a manifestation of the gap between the opinions of financial markets and the central bank, not necessarily as a sign of a better information base for the monetary policy authority. The shock then emerges when the financial markets’ opinions change. Let’s illustrate such a situation on a simple example. New data on inflation, which are lower than the central bank’s expectations, arrive in an environment of strongly negative sentiment about the growth conditions in the economy. Markets may thus be convinced that the central bank will decrease interest rates in reaction to this. The central bank does not lower rates at the meeting, but its communication moves in a more dovish direction. Paradoxically, this may lead to a rise in market rates after the central bank meeting. The monetary conditions are therefore tightened autonomously in response to the central bank’s communication, though it is moving towards an easing. The central bank’s communication would seem to have failed here, but in reality, there has only been a greater alignment of opinions. In the eyes of financial market participants, the central bank took into account the latest data and thereby reduced the likelihood of a future monetary policy error. The reaction of market rates cannot be easily explained without knowing the future economic story financial markets are working with. However, the outlook is not clearly defined (i.e. it is not sufficient to just use the analysts’ surveys[2]) and to a large extent it reflects financial market sentiment. If, in this situation, the central bank’s communication also places too much emphasis on current data and therefore unwillingly suppresses the information content of the forecast, it may conversely increase monetary policy uncertainty markedly.

ECB forecasts over the past three years[3]

Economic forecasting was challenging after the Covid pandemic. An analysis of the European Central Bank’s outlooks, illustrated in Charts 1 and 2, reveals shifts in the forecasts from 2022 to March 2024.[4] The analysis shows, for example, that the ECB’s March 2022 forecast did not fully reflect Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This discrepancy is due to considerable lags in the ECB’s forecasting process. For example, the basis for the March forecast is set in mid-February (the “cut-off date”). The process is further complicated by the fact that, twice a year, the forecasts for the individual countries are created in the Eurosystem national central banks. Although no detailed information is available on the ECB’s handling of new data after a forecast has been finalised, statements made at press conferences show caution and a tendency to postpone statements until a thorough discussion among experts has taken place. In turbulent times, ECB forecasts thus suggest that they do not reflect current events. In these situations, their communication is more concentrated on the debate about risks and alternative scenarios, but this may not be fully perceived by all financial market participants.

For example, since mid-2022 the European Central Bank’s forecasts predicted an acceleration in euro area growth, but the recovery keeps being postponed. As Charts 1 and 2 demonstrate, since the autumn of 2022, the picture for inflation had appeared stable at the one-year horizon, but the economic recovery was still not happening and the euro area stagnated. Nevertheless, the ECB nevertheless expected the weakness of the euro area to be overcome quickly. For comparison, the ECB’s GDP growth forecasts for 2007–2018 were met, but inflation forecasts lagged behind. Note that most of the forecasts for quarterly GDP growth point to between 0.3% and 0.5%, implying GDP growth in the range of 1.3%–2% in annualised terms.[5] We find a relatively similar picture for inflation – its forecast trend at the fourth quarter horizon in 2011–2013 was around 1.6%, then roughly in the 1.2–1.6% band until 2020. Inflation forecasts have been heading towards the 2% target in recent years.

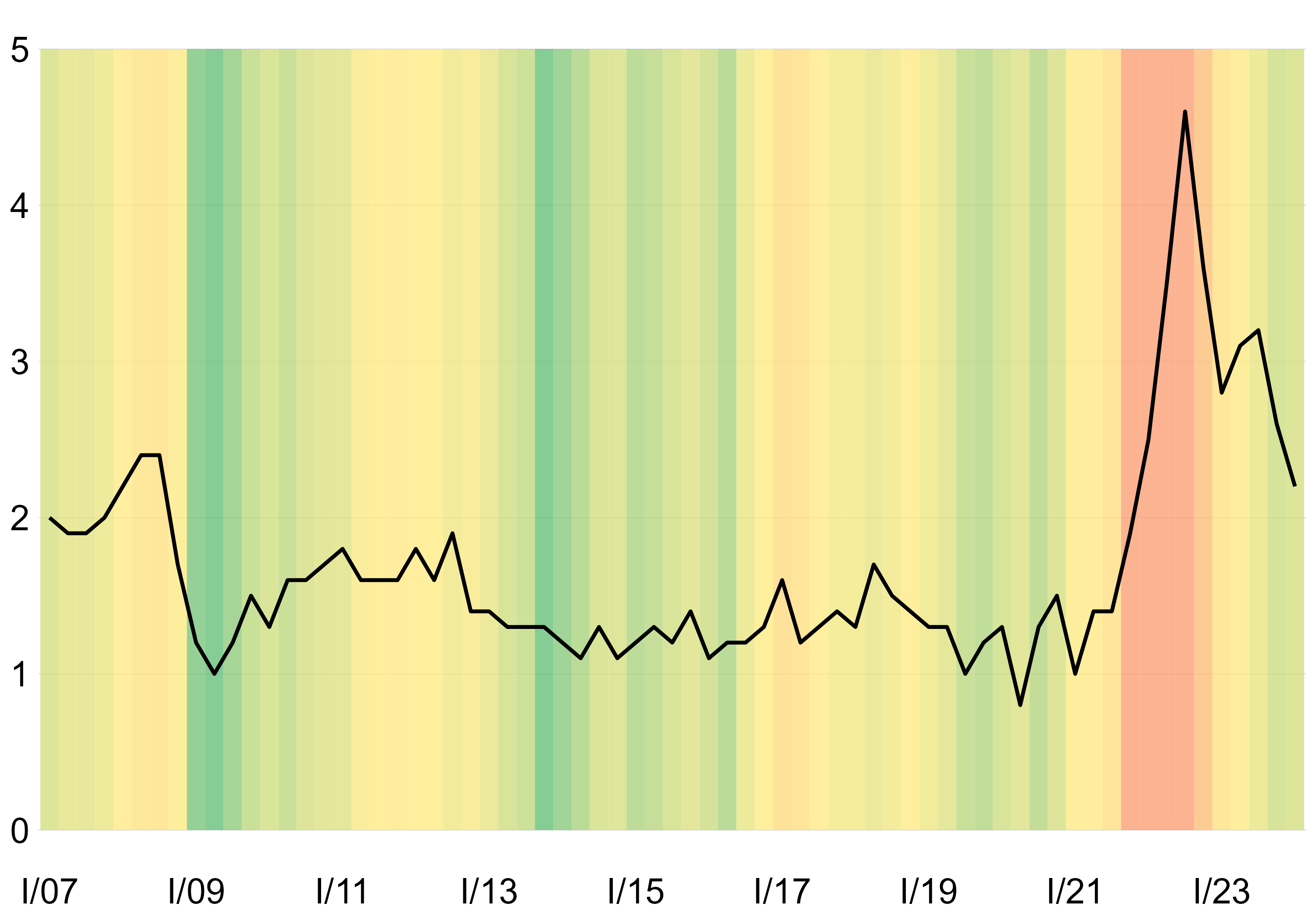

Discrepancies between financial market expectations and the ECB’s predictions are becoming particularly visible at times of growing concerns about a recession in the euro area. To better understand this phenomenon, we regularly follow an indicator of the probability of recession in the euro area, which is compiled by Bloomberg on the basis of a survey among analysts.[6]> Chart 3 illustrates the comparison of expected economic growth at the one-year horizon according to the ECB and the probability of recession represented by the colour span from red (high probability) to green (low probability). The diversity of opinions was particularly pronounced during the recession in the euro area in 2012 and the ECB’s expectations of a rapid revival, and also since 2022. At the start of 2024, the markets still predicted the onset of a recession in the euro area in the next year (orange) with a probability of more than 65%, whereas the ECB expected GDP growth to accelerate to 0.4% over the same timeframe. This discrepancy indicates that financial markets perceived weak performance of the euro area more negatively than the ECB and expected lower growth in the short term.

Chart 1 – ECB forecasts for GDP after 2021

Note: Q-o-q GDP growth in %. The caption shows the month of the forecast, i.e. 2022-03 is March 2022 (ECB winter forecast).

Source: ECB.

Chart 2 – ECB forecasts for inflation after 2021

Note: Y-o-y HICP inflation in %. The caption shows the month of the forecast, i.e. 2022-03 is March 2022 (ECB winter forecast).

Source: ECB.

Chart 3 – ECB GDP forecasts at the one-year horizon

Note: Q-o-q real GDP growth in % in the timeframe of one year; the probability of recession in the background; green is a low probability of recession; red is a high probability of recession. The latest ECB forecast included is from March 2024.

Source: ECB, Bloomberg.

Chart 4 – ECB inflation forecasts at the one-year horizon

Note: Y-o-y HICP growth in % in the timeframe of one year; surprise in inflation according to CITI; green is disinflationary/deflationary surprise; red is inflationary surprise. The latest ECB forecast included is from March 2024.

Source: ECB.

Market participants can have different expectations about inflation trends, especially if new inflation data are a surprise. During the autumn of 2023, speculation about the possibility of an early easing of the ECB’s monetary policy intensified, motivated by the unexpected dampening of euro area inflation trends. As Chart 4 shows, in the period when the development of inflation is surprising in a downward direction (a disinflation/deflation surprise), the inflation outlook from the ECB’s pen also moves lower. This was not different at the end of 2023, though according to the December forecasts, the ECB’s annual outlook was still relatively high. The y-o-y growth in the HICP was projected to hover above 2.5% in the course of this year, falling below 2% only in mid-2025. By contrast, some financial market analysts – as indicated by the comments – were expecting euro area inflation to reach the 2% target in late Q1 or early Q2.

It is not easy to determine whether financial markets were more surprised by trends in the real economy or inflation in the past. However, some indications can be provided by a regular Bloomberg survey among analysts held before each ECB meeting. This survey includes questions about changes in the ECB’s macroeconomic forecasts expected by analysts. Table 1 reveals the ratio of analysts expecting a downward revision to GDP and core inflation. Downward revisions were expected for GDP from June last year onwards, so the analysts perceived a conflict regarding the GDP forecast and actual trends. However, a remarkable jump can be seen in the outlook for core inflation ahead of the ECB’s December meeting, which may reflect an unexpected decline in euro area inflation in November 2023. The vision of the euro area economy, as formulated by the ECB, no longer seems fully consistent with the incoming data for financial markets. This raises the question of whether financial markets have worked with different scenarios for the euro area economy this year.

Table 1 – Responses from analysts as a part of a Bloomberg survey to the question “How do you expect the ECB to revise its macroeconomic forecasts” prior to an ECB meeting?

| Share of “downwards” responses for the GDP outlook | Share of “downwards” responses for the core inflation outlook | |||||||

| 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

| March 2023 | 3% | 40% | 14% | March 23 | 4% | 18% | 25% | |

| June 2023 | 43% | 70% | 3% | June 23 | 18% | 25% | 19% | |

| September 2023 | 92% | 84% | 4% | September 23 | 13% | 50% | 46% | |

| December 2023 | 76% | 79% | 15% | December 23 | 71% | 71% | 45% | |

| March 2024 | 67% | 40% | March 2024 | 63% | 29% | |||

Note: The month in the first column indicates the month of the survey and the columns indicate the years about which the survey was directed.

Economic trends in the euro area thus indicated possible future developments which could differ substantially from the macroeconomic outlook presented by the ECB.[7] This can be illustrated by the wage outlook, the importance of which was repeatedly stressed by the ECB. If financial markets considered (albeit only technical) recessions likely in the euro area, they did not have to have confidence in robust growth in demand or in wages either. Moreover, the slowdown in wage growth was also confirmed by high-frequency indicators – e.g. the Indeed Wage Tracker (IWT), which tracks wage growth in advertisements on the Indeed portal. The IWT usually anticipates actual wage growth by six months and clearly indicated a slowdown in wage growth at the beginning of the year. Wage bargaining in Germany was also moderate. As in the last two years, any improvements for employees were channelled into bonuses. Financial markets were also able to assess risks differently or assess other assumptions associated with a forecast. The factors that might have entered the analysts’ considerations include a further sizeable fall in exchange prices for energy (gas in particular) at the start of the year, the abating effect of problems in container transport and limited profitability of corporations amid weaker demand.

Surprises in ECB monetary policy and communication

One further interpretation may be that financial markets tried to prepare for a possible sharp reversal in the ECB’s monetary policy or had a different view of the central bank’s reaction function. Investors could draw on historical experience – when the ECB is surprised by the macroeconomic situation and starts cutting rates later, they do so more sharply. We do not have a specific rate trajectory with which the members of the ECB’s Governing Council would agree so that we can compare it with market expectations. However, some ECB representatives clearly signalled the first rate cut in the past only in the summer. Following the expected fall in June, four meetings of the Governing Council (July, September, October and December) remain until the end of the year. A new forecast, which usually serves as a basis for changing the monetary policy stance, will only be presented at two of them (September and December). In the January market outlook with 5–6 standard rate reductions by the end of 2024, this suggests that the market outlooks expected rates to be cut earlier and/or more aggressively than just 0.25 percentage point at some meeting. Inflation would have to fall below 2% and the outlook for economic activity would have to deteriorate significantly in order for the ECB to consider such dramatic monetary policy easing as foreseen by the market outlook.

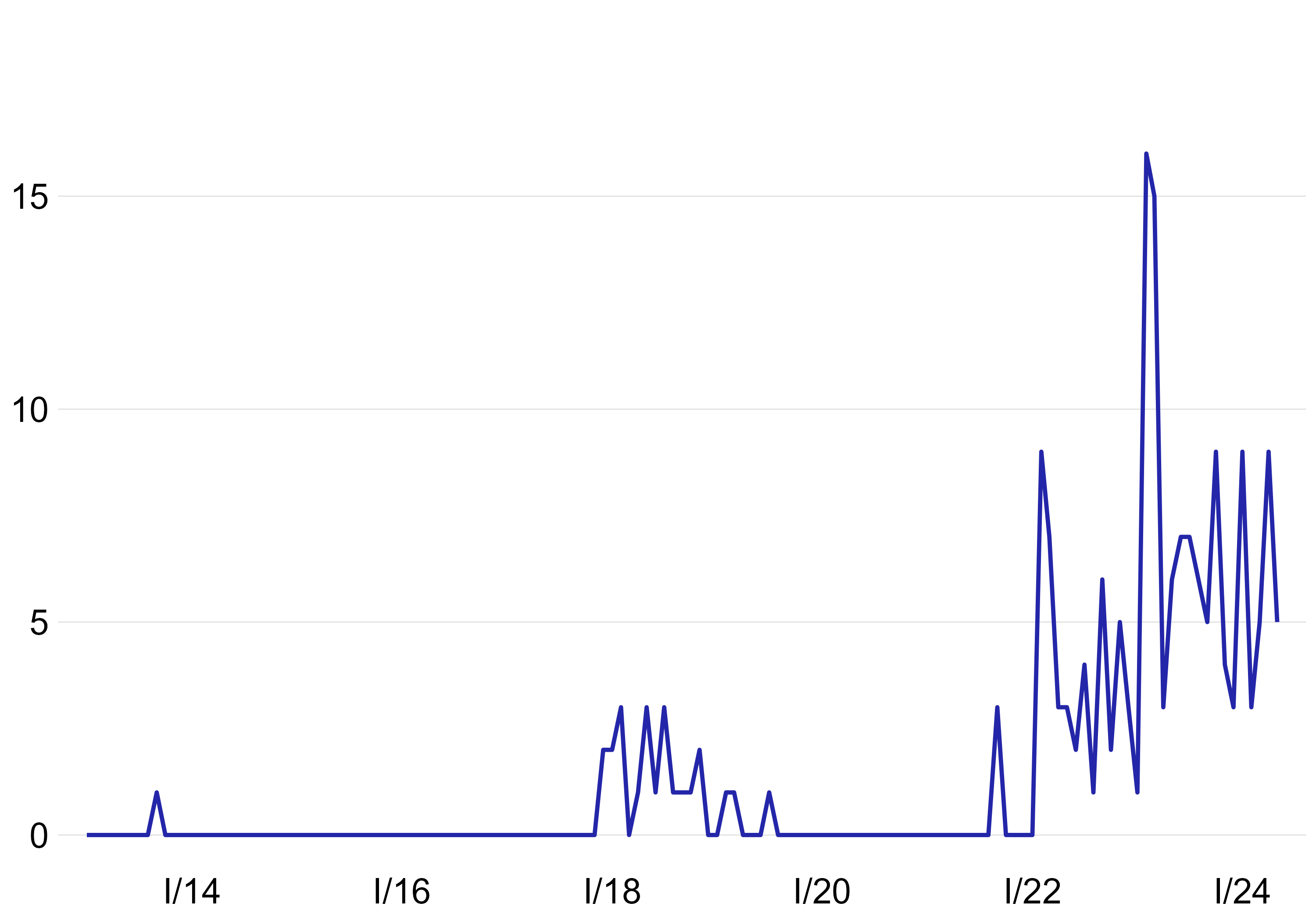

Chart 5 – Importance of recent data in ECB communications

Note: The number of uses of the term “data-dependent” per month in speeches and interviews by Governing Council members or at ECB press conferences. Source: ECB website.

In addition, central bankers’ communications emphasised the importance of the latest economic data. This is apparent, for example, from the frequent use of the term “incoming data-dependent decision”,[8] which has become increasingly included in their statements since the start of 2022, as shown in Chart 5. Following the January ECB meeting, for example, the Croatian governor emphasised that market rate changes of 0.25 percentage point were considered to be a smoother way of implementing monetary policy, but that greater intervention was not ruled out if the current data supported this. This approach may have increased market concerns about surprise changes, which may have led to a greater willingness to hedge against such scenarios, especially if new data indicated a higher probability. Central bankers can also make markets uncertain about their confidence in official forecasts in this way. Although the adjustment of monetary policy actions in response to newly available data is a natural part of monetary policy, an excessive emphasis on a “data-dependent” approach may thus lead financial markets to over-sensitivity to new data. Nevertheless, the governors’ cautious approach is understandable as the euro area economy has faced more structural difficulties or cost shocks than in a traditional business cycle in recent years.

However, the central bank’s credibility was not fundamentally impaired. Though the ECB was criticised – especially in 2021 – for the insufficient anticipation of the pick-up and persistence of inflation. In the January 2023 survey mentioned in Table 1, more than half of the analysts reported that the ECB was “behind the curve,” i.e. reacting late. However, the results of a Financial Times survey from December 2023 showed that more than half of the respondents do not think that the ECB’s credibility was seriously undermined by the late reaction, while one-third feel that its reputation was damaged.

The opinions of the ECB and financial markets have gradually become aligned, with the market outlook for interest rates shifting upwards, bringing it closer to the ECB’s communication. Euro area inflation trends since February 2024 have not confirmed the fears of financial markets concerning a disinflationary recession, but signs of a recovery in the euro area were conversely stronger. Sentiment in business remained negative, but activity in industry emerged from the decline. According to the indicator mentioned above, the probability of recession in the following year even decreased to 40%. Even Bloomberg’s March survey among analysts confirmed that the expectations of further corrections in the ECB forecast (both inflation and GDP) are decreasing (the last line of Table 1). At its April meeting, the ECB left rates unchanged, but in its communication (in line with market expectations), it repeated its readiness to lower rates in June, which it subsequently did. However, the aggressiveness of further ECB interest rate cuts in the rest of this year is also uncertain with regard to future trends in inflation. A more cautious approach, with the ECB not rushing to further rate cuts, now seems likely, to which financial markets responded by adjusting the rate outlook upwards.

Conclusion

To sum up, the ideal situation is that a central bank’s actions and communications are in line with financial market expectations. It is important for a central bank to monitor market expectations. A gap regarding interest rates between them may lead to an autonomous tightening or easing of monetary policy, which may not be desirable from a central bank’s perspective. Moreover, unexpected monetary policy decisions will often lead to increased market volatility. However, at times of high uncertainty, there may be different perceptions of the macroeconomic situation between markets and a central bank, and some gaps in expectations about future trends in interest rates may be inevitable in such a situation. A central bank must then take account of this gap, but should not be bound by it. Its task is to set monetary policy in such a way as to fulfil its mandate, not so that it does not surprise financial markets (though it is ideally the same). Over time, markets and the central bank see how the economy continues to develop, which may lead to gradual convergence of their positions. This, after all, also explains the fading discrepancies between market expectations and the ECB’s communications so far this year.

Literature

Altavilla, C., Gürkaynak, R. S., Motto, R., & Ragusa, G. (2020). “How do financial markets react to monetary policy signals?” European Central Bank, Research Bulletin No. 73. (external link)

Benchimol, J., Saadon, Y., & Segev, N. (2023). “Stock market reactions to monetary policy surprises under uncertainty,” International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 89, 102783. (external link)

ECB (2016). “A guide to the Eurosystem/ECB staff macroeconomic projection exercises,” European Central Bank. (external link)

IMF (2002). “Market Predictability of ECB Policy Decisions: A Comparative Examination,” International Monetary Fund, WP/02/233. (external link)

Jarociński, M., & Karadi, P. (2020). “Deconstructing monetary policy surprises: The role of information shocks,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 12(2), 1-43. (external link)

Kaminska, I., Mumtaz, H., & Šustek, R. (2023). “Monetary policy surprises and their transmission through term premia and expected interest rates,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 124, 48-65. (external link)

Oliveira, S., & Simon, P. (2023). “Interpreting monetary policy surprises: Does central bank credibility matter?” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. (external link)

Sastry, K. A. (2022). “Disagreement About Monetary Policy.” (external link)

Sekandary, G., & Bask, M. (2023). “Monetary policy uncertainty, monetary policy surprises and stock returns,” Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 124, 106106. (external link)

Sinha, A., Topa, G., & Torralba, F. (2023). “Why Do Forecasters Disagree about Their Monetary Policy Expectations?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Liberty Street Economics. (external link)

Wilhelmsen, B., & Zaghini, A. (2011). “Monetary policy predictability in the euro area: an international comparison,” Applied Economics, Vol. 43(20), 2533-2544. (external link)

[1] The potential discord also affects the CNB’s forecast, based on the market outlook for interest rates in the euro area. The foreign rate outlook is noticeably reflected in the forecast for the domestic monetary policy stance through the interest rate differential channel.

[2] A whole range of surveys among financial market analysts are available – the Survey of Professional Forecasters, Consensus Economics and Bloomberg. However, comments on financial markets can also be used to better capture sentiment.

[3] The macroeconomic forecast is a key input into the central bank’s monetary policy decisions. The ECB forecast is produced by the ECB’s and national central banks’ specialist departments and is referred to as the “Staff Forecast” in ECB communications. However, the Governing Council is consulted about it, so we will talk about the “ECB forecast” in our analysis. In the ECB’s case, the forecast is conditional on the market outlook for interest rates. For more details see, for example, ECB (2016) or Spotlight in Central Bank Monitoring III/2023.

[4] The newly published June forecast is not taken into account in the analysis.

[5] A closer look at 2011–2019, except for the main crisis, reveals only one forecast (winter 2013), where quarterly GDP growth was not within this range at the one-year horizon. This tendency is common among the analysts using structural forecasting models and is not limited to central banks. The formula is also repeated in the forecasts from mid-2022, where the GDP growth target over the 1-year horizon remains stable at 0.4%.

[6] In our historical experience, this indicator better captures changes in financial market sentiment than a standard survey of the outlook for macroeconomic variables among analysts, where there is a tendency to monitor the central bank’s behaviour and communications more closely and they may not send early signals of a coming recession.

[7] As the ECB outlined in the December forecast, the assumptions about household consumption and inflation were crucial: “Moreover, declining inflation and rising wages, in the context of a still tight labour market, should support households’ purchasing power around the turn of the year,” and “Stronger wage growth also implies that losses in purchasing power incurred since the surge in inflation are expected to be recovered by the end of 2024, which is slightly earlier than expected in the September projections”.

[8] Using webscraping, we analysed speeches, interviews and other official statements of the Governing Council members, as presented on the ECB’s website.