The impact of artificial intelligence on the labour market

Applications of artificial intelligence (AI) are developing rapidly. The current period of emergence of generative AI models is still too short to provide reliable empirical evidence on their impact on the labour market. Most studies agree that the expansion of generative AI will bring significant changes. Considering past waves of automation and robotisation, the widespread use of AI can be expected to generate productivity gains, for example. However, those gains are currently difficult to quantify. There are many benefits associated with AI, but also certain risks, in particular concerns about job losses in certain fields where workers may be replaced by the new form of intelligence. This may have negative social and distributional consequences. Therefore, it is important to address the risks and manage the development of AI in a way that minimises the risks without negating the benefits. The literature is actively addressing the risks and benefits of AI.

This article is structured as follows. First, the benefits and risks of AI are discussed. The second part summarises the most relevant studies. This overview focuses on the labour market and does not deal with general issues of how AI works. For this, one can refer to the April 2024 cnBlog article by Komárek and Ryšavá (2024), which presents in more detail what AI actually is, what its different forms are, how it has developed in recent years and what its economic impact is.

Artificial intelligence has many benefits…

Increasing productivity and efficiency and creating new job opportunities are important benefits of AI. The impact of AI on the labour market can be viewed as part of a broader context of technological change, including automation. However, unlike previous waves of automation, a distinctive feature of AI is its broad application across a wide range of occupations (Oschinski, 2023).

Increasing productivity and work efficiency is also a key channel for supporting economic growth. According to a joint survey conducted by the British Centre for Macroeconomics (CfM) and the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) in May 2023, most members of its European panel believe that AI will contribute up to two percentage points per year to overall economic growth over the next ten years (Ilzetzki and Jain, 2023). However, the panellists express a considerable degree of uncertainty about their predictions.

AI is expected to affect all wage levels. However, data from the US suggest that higher-paid jobs may be more exposed to the requirement for knowledge of specific AI tools, for example large language models (LLMs), such as Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs), and LLM-powered software (Eloundou et al., 2023).

According to a 2022 OECD survey covering the US and selected developed countries, including EU member states (France, Germany, Italy and Spain), it appears that AI helps highly skilled workers do their jobs better rather than replacing them. The impact on employment may manifest over a longer time scale. Productivity gains are subsequently reflected in wage increases for workers who use AI.

Korinek (2024) provides examples of how AI, and in particular LLMs such as ChatGPT, can assist economists in their work and increase their productivity. AI can be used in a variety of ways, such as for automating small tasks, helping with idea generation, serving as a personal research assistant and facilitating data analysis and programming.

Besides raising productivity, AI can have a positive impact on the quality of work by contributing to a subjective sense of “joy of work” through the automation of routine tasks. An experiment conducted among college-educated professionals in the US produced a similar conclusion (Noy and Zhang, 2023). The participants were tasked with using the ChatGPT LLM to solve moderately difficult professional writing tasks. Those who had ChatGPT were more productive and efficient and enjoyed the tasks more. Remarkably, participants with lower skills benefited the most from ChatGPT. This finding contributes to the debate on how AI can be used to reduce productivity inequality (and consequently income inequality).

Another benefit is the potential to reduce income inequality by increasing the productivity of less skilled workers. Thanks to the use of AI technologies, less qualified workers can now perform tasks that previously required many years of education and experience (Agrawal et al., 2023). In this way, AI can help reduce income disparities.

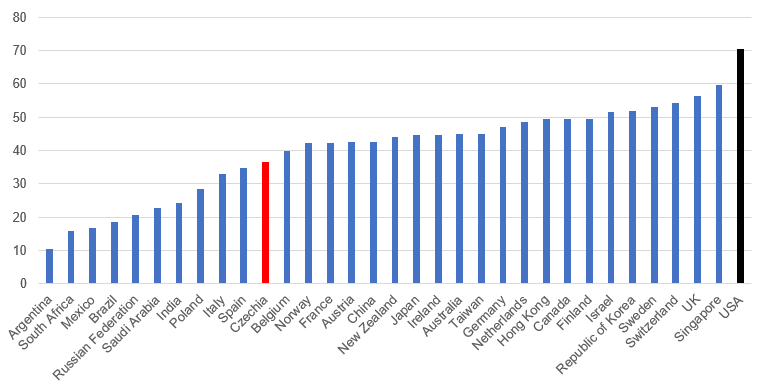

Capital Economics’ AI Economic Impact Index suggests that the US will be at the forefront and one of the main beneficiaries of the AI revolution. This will increase its dominance over the euro area (Chart 1). The Czech Republic ranks alongside countries such as Spain and Belgium and has considerable potential to take advantage of the opportunities offered by new AI technologies due to its solid industrial base.

Chart 1 – AI Economic Impact Index

Source: Capital Economics (2023). Note: The index assesses the potential economic impact of AI and ranges from 0 to 100, where 100 = maximum impact. It evaluates the extent to which AI advancements are likely to affect various economic factors such as productivity, GDP growth and employment in different countries.

…but there are also associated risks

A negative impact on jobs and wages is one of the risks associated with AI. From a theoretical perspective, the impact of AI on employment and wages is ambiguous and may depend strongly on the type of AI, the way it is deployed, market conditions and policy decisions. Empirical evidence based on the types of AI developed and applied over the past ten years does not suggest that employment and wages have declined in professions more exposed to AI. Humans remain an essential part of the process. However, the rapid pace of development of AI does not preclude future changes.

So far, there is little evidence of reduced demand for labour due to the application of AI. According to a survey conducted in 2022 in selected OECD member countries, developments in the next ten years, rather than the data observed to date, are the primary cause for concern at the moment (OECD, 2023). In the similar 2023 CfM-CEPR survey, the reasons for uncertainty include worries that AI will increase unemployment and inequality, at least in the short to medium term, and thus affect productivity and growth (Ilzetzki and Jain, 2023).

The literature suggests that occupations dominated by low-skilled workers are more likely to be at risk. On the other hand, it is precisely these groups of workers who can benefit the most from AI, if it is used in the right way.

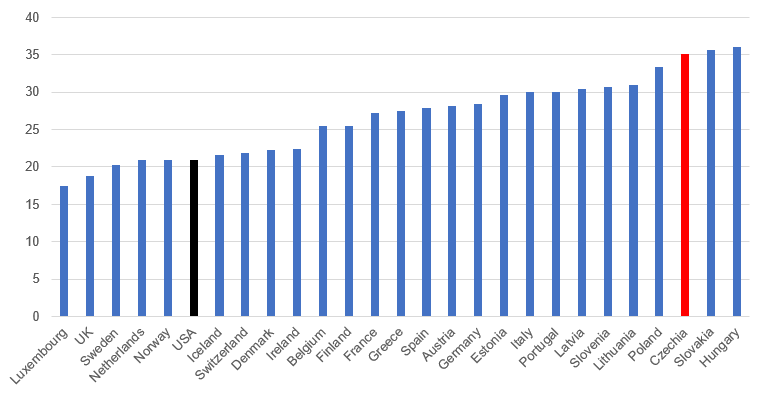

OECD (2023) identifies occupations at risk of automation. Their share of total employment is shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2 – Employment shares in occupations with the highest risk of automation by country, %

Source: OECD (2023), Figure 4. Results of a survey among experts asked to assess the degree of automation of approximately 100 skills and abilities (Lassébie and Quintini, 2022).

In the Czech Republic, the share of employment in occupations at the highest risk of automation is 35%. This is significantly higher than the OECD average of 27% and also higher than in the US, where the rate is 21%. However, the higher potential for automation also represents an opportunity (according to Chart 1), so the overall impact of AI will depend on the measures that accompany its implementation.

Most of the panellists in the CfM-CEPR survey conducted in the UK in May 2023 believe that AI is unlikely to cause significant changes in employment rates in high-income countries. The rest are divided between predictions of increased and decreased unemployment rates. The panellists thus express a considerable degree of uncertainty about their predictions, as AI is still in its infancy (Ilzetzki and Jain, 2023).

Other risks associated with the deployment of AI include intensifying work pace and psychological discomfort for workers managed by AI (Lane and Saint-Martin, 2022). Moreover, there are ethical challenges related to personal data protection, automated decision-making and responsibility issues (OECD, 2023).

Summary of findings from the current literature: the overall impact of AI is neutral, but significant heterogeneity (job reallocation) is evident at the micro level

According to Acemoglu et al. (2022), who looked at online job vacancy data in the USA since 2010, AI has not had a significant impact on employment in occupations more exposed to it. However, for firms using AI, reallocation of jobs can be seen, with fewer new hires for positions not related to AI. The overall effects of this job reallocation are not yet clear.

Oschinski (2023) examines the effects of AI on the German labour market, noting that while some job losses can be seen in manufacturing and logistics, there is evidence of job creation in technology and positions involving human-AI collaboration. The impact of AI varies by industry, benefiting high-tech and health care sectors while posing challenges for traditional industries. Regions such as Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, which have a strong technological focus, can benefit more. The study underscores the importance of proactive policies, such as retraining programmes and support for at-risk workers. Despite the potential for AI to boost productivity and create jobs, targeted measures are necessary to minimise the negative impacts and facilitate a smooth labour market transition.

Albanesi et al. (2023) look at how AI-enabled technologies affected employment in 16 EU countries from 2011 to 2019. The spread of AI brings both opportunities and risks. The study finds evidence of rising employment shares in occupations with younger and higher-skilled workers, and declining employment shares in some other occupations. The overall impact on jobs depends on whether AI-enabled technologies replace or complement the workforce. Even though there are big differences among European countries, the general finding is that AI has not had a negative effect on employment overall.

Hötte et al. (2023) evaluate the impact of technological change on employment over the last 40 years. While new technologies can lead to job losses in some cases, they often create new types of jobs and increase productivity. The authors note that blue-collar workers have been adversely affected and emphasise the need for good retraining programs. The article concludes that fears of widespread unemployment due to new technology are not really backed by empirical evidence, and stresses the importance of supporting displaced workers.

Acemoglu (2024) looks at how AI affects the economy and finds that its impact on total factor productivity is quite mild, with an expected increase of just 0.66%–0.71% over ten years. These gains will likely shrink over time, as early AI applications target simple tasks, while future ones will involve more complex tasks. The article also explores how AI affects wages and inequality, suggesting that while AI can boost productivity for low-skilled workers, it might still increase inequality, because many low-income, less-skilled workers do jobs that are not easily automated. Although the impact on inequality is not as clear as with past automation waves, AI is expected to widen the income disparities between capital and labour. Additionally, some new AI-driven projects, such as online manipulation of voters or consumers, could have negative social impacts, which should be considered in economic evaluations.

An IMF study (Brollo et al., 2024) also points out the risk of increasing income and wealth inequality. Highly skilled workers who can use AI technologies might effectively see boosts in productivity and wages, while some lower-skilled workers may face job losses or stagnant wages. This could lead to polarisation within income groups, with more benefits going to higher-income individuals and those owning AI-related assets.

Conclusions

Artificial intelligence is rapidly evolving, and the empirical evidence on the impact of AI on the labour market has yet to produce definitive conclusions, especially at the aggregate level. At the level of individual industries or sectors, however, some reallocation can be observed – the creation of new AI-related jobs and the disappearance of other, usually lower-skilled, positions. AI is expanding dynamically but has not had significant overall impacts so far. The future balance of benefits and risks will depend on the mode of implementation and the accompanying measures.

In conclusion, AI can significantly boost productivity and work efficiency, especially in routine or physically demanding tasks, while also allowing people to use their unique human capabilities. The same AI applications, however, can also pose significant risks to the work environment, especially if used improperly or solely to reduce costs. Historical waves of technological progress have often led to the relative redistribution of income towards those able to utilise the new technology, but rarely to overall growth in unemployment or a decline in living standards. Similarly, according to current research, AI seems to be more of an opportunity than a threat for advanced economies.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Czech National Bank. The author would like to thank Jakub Matějů and Jan Brůha for their valuable comments.

References

Acemoglu D. (2024): The Simple Macroeconomics of AI. NBER Working Paper No. 32487. http://www.nber.org/papers/w32487

Acemoglu D., Autor D., Hazell J., Restrepo P. (2022): Artificial intelligence and jobs: Evidence from online vacancies. Journal of Labor Economics, 40(S1), pp. S293-S340. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/718327

Agrawal A., Gang J. S., Goldfarb A. (2023): Do We Want Less Automation? Science, 381(6654), pp. 155-158. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh9429

Albanesi S., Dias da Silva A., Jimeno J. F., Lamo A., Wabitsch A. (2023): New technologies and jobs in Europe. Working Paper No. 2831, European Central Bank. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2831~fabeeb6849.en.pdf

Brollo F., Dabla-Norris E., de Mooij R., Garcia-Macia D., Hanappi T., Liu L., Minh Nguyen A. D. (2024): Broadening the Gains from Generative AI: The Role of Fiscal Policies. IMF SDN/2024/002. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2024/06/11/Broadening-the-Gains-from-Generative-AI-The-Role-of-Fiscal-Policies-549639

Capital Economics (2023): AI Economies and Markets: How artificial intelligence will transform the global economy. October 2023 report. https://www.capitaleconomics.com/ai-impact-economy

Eloundou T., Manning S., Mishkin P., Rock D. (2023): GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models. Papers 2303.10130, arXiv.org. http://arxiv.org/abs/2303.10130

Hötte K., Somers M., Theodorakopoulos A. (2023): Technology and Jobs: A Systematic Literature Review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 194, pp. 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122750

Ilzetzki E., Jain S. (2023): The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Growth and Employment. VoxEU.org, 20 June 2023. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/impact-artificial-intelligence-growth-and-employment

Komárek L., Ryšavá M. (2024): The rise of artificial intelligence: Does humanity have a revolutionary yet double-edged weapon? Global Economic Outlook, March 2024, VI. Focus, pp. 14-20. Czech National Bank. https://www.cnb.cz/export/sites/cnb/en/monetary-policy/.galleries/geo/geo_2024/gev_2024_03_en.pdf

Korinek A. (2024): Generative AI for Economic Research: Use Cases and Implications for Economists, 2024Q2 Update. Journal of Economic Literature, Dec. 2023, 61(4), pp. 1281-1317. https://www.korinek.com/

Lane M., Saint-Martin A. (2021): The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Labour Market: What Do We Know So Far? OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 256, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/7c895724-en

Lassébie J., Quintini G. (2022): What Skills and Abilities Can Automation Technologies Replicate and What Does It Mean for Workers? New Evidence. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 282, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/646aad77-en

Noy S., Zhang W. (2023): Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Science, 381(6654), pp. 187-192. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh2586

OECD (2023): OECD Employment Outlook 2023: Artificial Intelligence and the Labour Market. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/08785bba-en

Oschinski M. (2023): Assessing the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Germany’s Labor Market: Insights from a ChatGPT Analysis. MPRA Paper 118300, University Library of Munich, Germany. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/118300/