The saving rate in the euro area and the Czech Republic – potential for growth in consumption?

This article compares growth in household consumption, the saving rate and investment in the euro area and its largest economies with that in the Czech Republic. The comparison with euro area countries in a similar situation reveals that Czech households spent much less in response to the energy crisis amid a significantly higher saving rate relative to the long-term average. But Czech households did not channel their savings into housing, instead preferring to invest in liquid assets, probably for precautionary reasons. Their interest in financial products was boosted by rising interest rates. There are similar trends in a number of large euro area economies, where households’ current high propensity to save can be expected to decline. However, the decline will be hindered by higher interest rates in the near future in the euro area, where the policy thightening cycle is peaking only now. By contrast, as interest rates in the Czech Republic probably reached their top already last year, Czech households’ current high propensity to save is opening up room for a faster recovery in consumption growth than in the euro area.

Published in Global Economic Outlook – August 2023 (pdf, 1.5 MB)

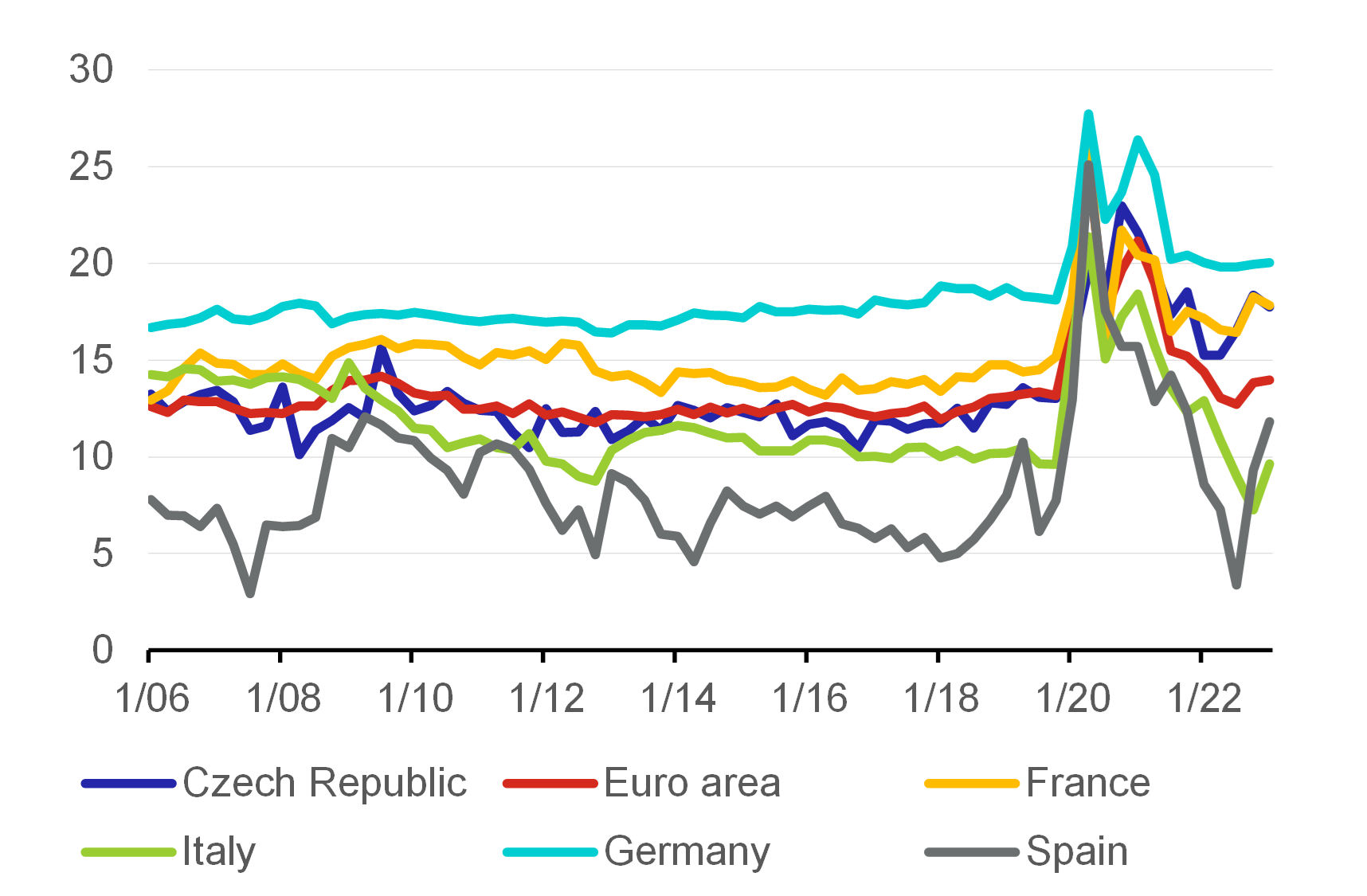

The saving rate varies across euro area countries but rose in all of them during the pandemic

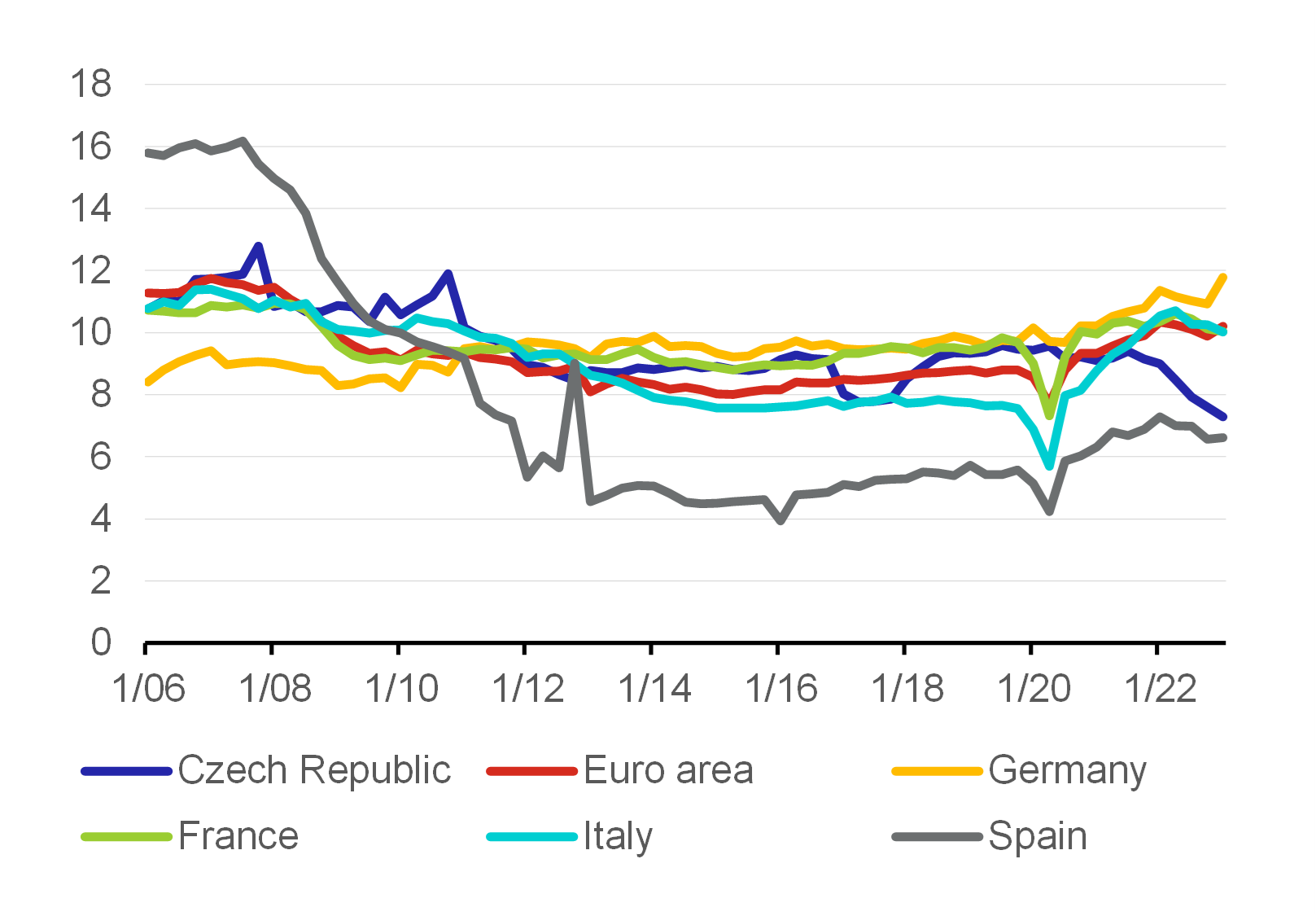

The saving rate differs historically across euro area countries (see Chart 1). Among the large euro area economies, it is traditionally highest in Germany (well above the euro area average) and lowest in Spain. In the Czech Republic[1] it was near the euro area average of around 12% until the onset of the pandemic. Consumers’ attitude to saving in different countries has also differed across the crises that have hit the world since the start of the new millennium – the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) after the collapse of Lehman Brothers (2009), the Covid-19 pandemic (2020–2021) and the energy crisis and the escalation of international tensions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (2022). For example, as Chart 1 shows, the rise in the saving rate seen during the GFC was practically unobservable compared to recent crises. This can probably be attributed to the indirect link between uncertainty in the financial system and the approach of individual economic agents (households and firms) to creating reserves.

Chart 1 – The household saving rate

(gross rate in %)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Seasonally adjusted.

Glossary

The gross saving rate of households is defined by Eurostat as gross savings divided by gross disposable income adjusted for the change in the net equity of households in pension funds reserves. Gross savings are the part of gross disposable income that is not spent as final consumption expenditure. This rate is calculated on the basis of quarterly sectoral accounts data by institutional sector.

The gross investment rate of households is defined by Eurostat as gross fixed capital formation divided by gross disposable income adjusted for the change in the net equity of households in pension funds reserve. Household investment consists mainly in purchasing and renovating dwellings. This rate is calculated on the basis of quarterly sectoral accounts data by institutional sector.

Numerous euro area countries saw sizeable growth in savings during the Covid-19 lockdowns, especially after the first wave of the pandemic (see Chart 1). This growth was far higher than during the 2009 GFC. The rise in the saving rate was driven by forced unwanted savings created by households because many types of goods and especially services were not available to buy. Examples included eating out and travel, as businesses were closed under anti-pandemic measures.[2] Fiscal transfers stabilised household income, so the forced saving merely represented consumption deferred to the future. The saving rate in Germany surged above 27% in 2020 Q2 but started to decline towards the long-term average after the lockdowns as households made deferred purchases.

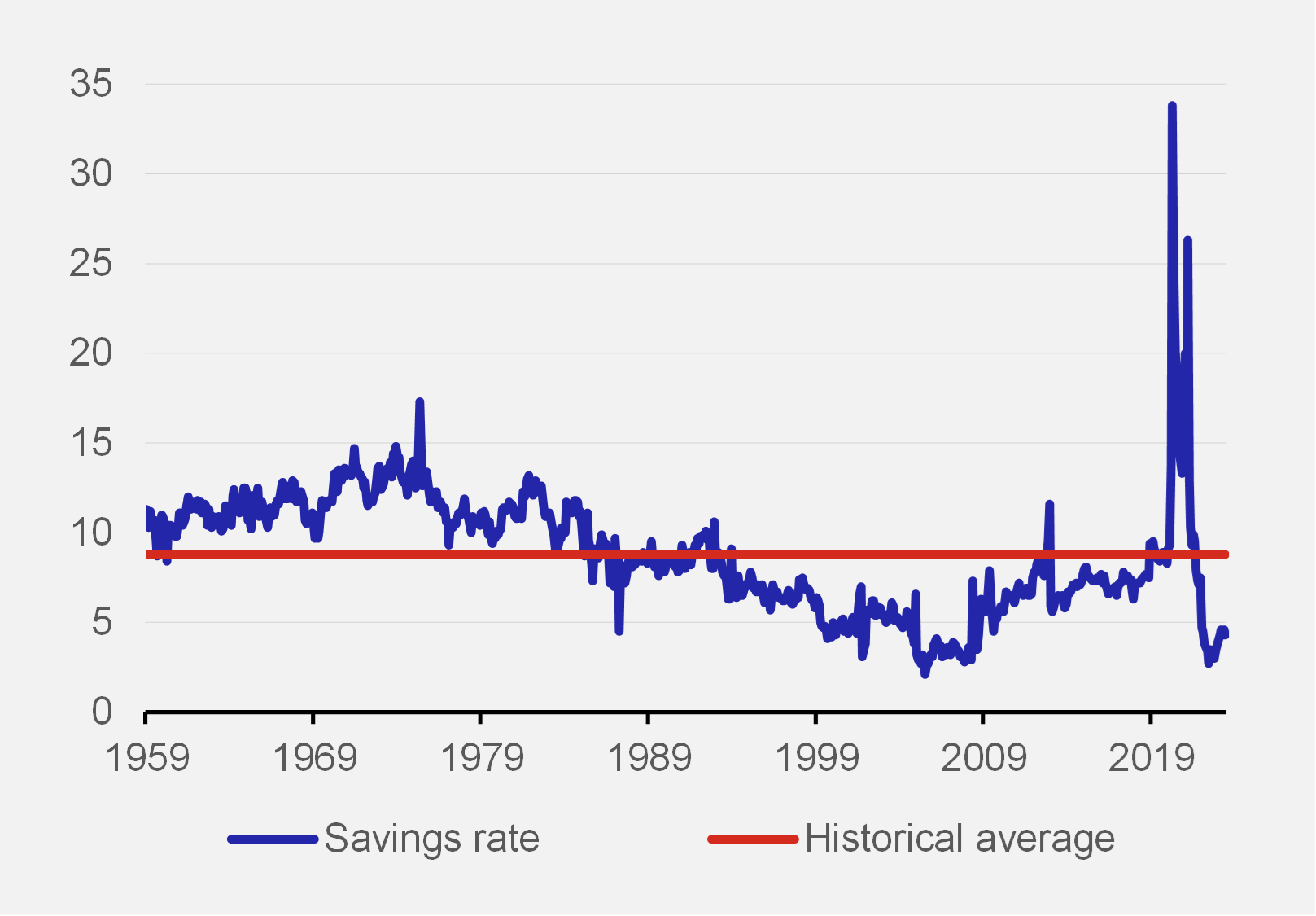

Box 1 – The post-pandemic release of savings in the USA

Like in Europe, private savings in the USA surged in response to the pandemic lockdowns, but unlike in Europe, the saving rate did not rise in winter 2022/2023. In contrast to previous recessions, the US government responded to the pandemic with an unprecedented package of support measures totalling USD 5 trillion in 2020–2021. As many of these were aimed directly at households (unemployment benefit, the child tax credit and others), households’ personal savings grew rapidly, far exceeding the pre-Covid trend. As Chart 1 BOX shows, the personal saving rate jumped from near 9% before the pandemic to over 20% during the strictest lockdowns. After the pandemic ended, however, it began to fall appreciably below the pre-pandemic historical average (8.8%). Since early 2022, it has been fluctuating below 5%.

Chart 1 BOX – The personal saving rate in the USA

(%)

Source: FRED

Note: Seasonally adjusted.

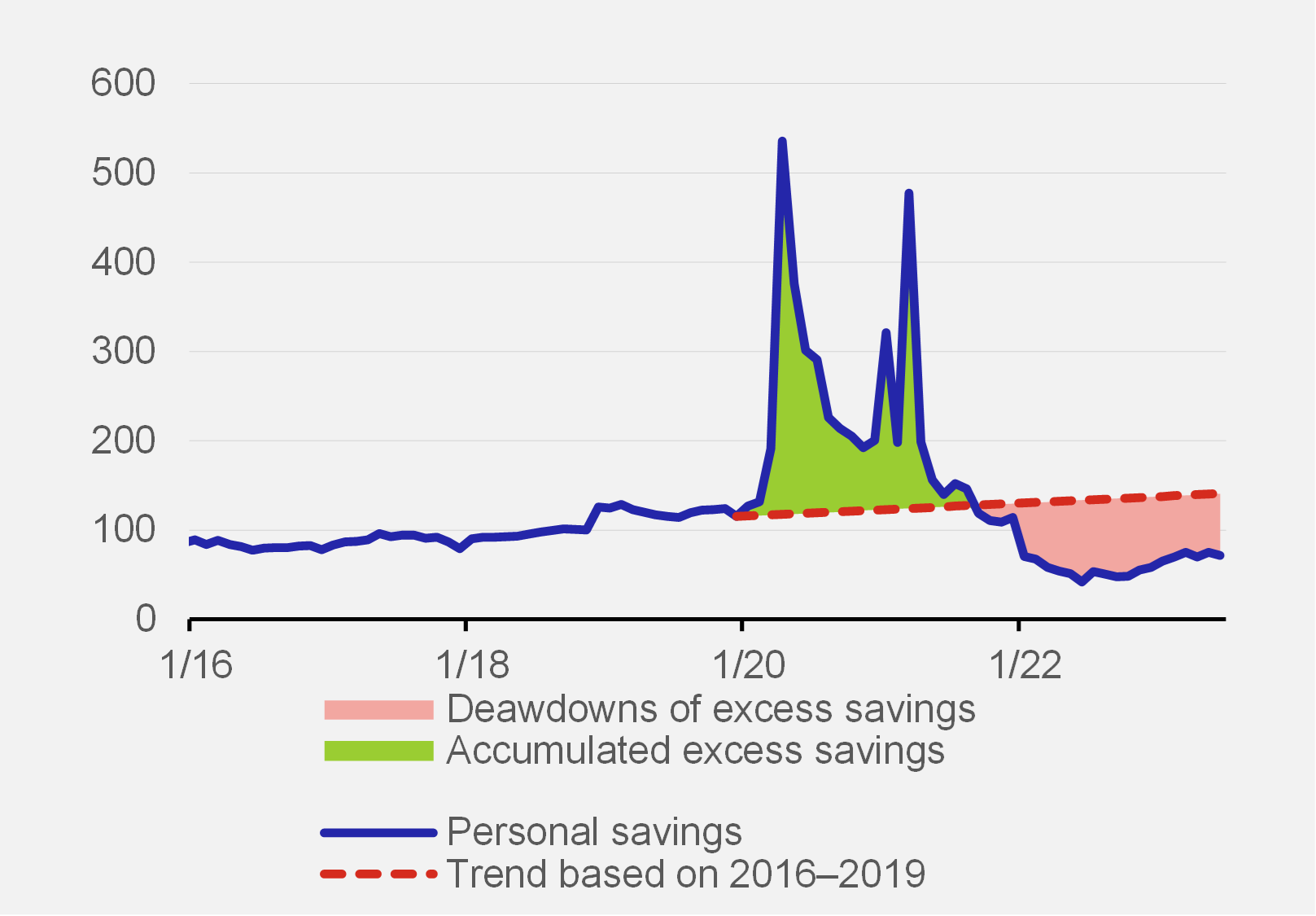

US households have therefore been gradually releasing their accumulated savings since 2021 Q3 and this trend is set to persist until the end of 2023. According to estimates made by the San Francisco Fed (2023), accumulated excess savings in nominal terms totalled about USD 2.1 trillion in August 2021 (see Chart 2 BOX; green area). Initially, the drawdowns of savings were slow (USD 34 billion a month on average between September and December 2021). Later on, they accelerated to around USD 100 billion a month on average for 2022 as a whole. In 2021 Q1, they slackened again to USD 85 billion a month. Cumulative drawdowns amounted to USD 1.6 trillion in March (red area). This means that excess savings of around USD 500 billion are left in the economy. If the current pace of drawdown were to persist, excessive savings would probably continue to support household spending at least until 2023 Q4.

Chart 2 BOX – Personal savings versus the pre-pandemic trend

(billions USD)

Source: Authors’ calculation, St. Louis Fed

Note: Based on Abdelrahman and Oliveira (2023), seasonally adjusted.

As the USA was not affected by the energy crisis, the release of savings was able to boost household consumption in America while Europe was saving. The post-pandemic recovery of the US economy was surprisingly strong, boosted considerably by the release of savings. By contrast, Europe experienced further shocks, which made households cautious.

After the pandemic ended, however, the saving rate in euro area countries did not return to the pre-2020 level. Take Germany, for example, where the average saving rate was 17.4% in 2011–2018 but has been just below 20% since mid-2021. Similar effects can be found in other euro area countries, although the differences from the long-term average were not large in all of them. Euro area households thus responded differently to the re-opening of economies after the pandemic and have yet to return fully to their usual pre-Covid consumer behaviour. According to the theory, households were expected to release their forced savings in consumption over the course of several quarters, as was the case in the USA (see Box 1).

There are several motives for the higher rate of saving after the pandemic.[3] High-income households are responsible for a large part of the savings created during the pandemic (the saving rate increases as we move to higher income quintiles). They are characterised by a lower marginal propensity to spend out of income or wealth than low-income households. Moreover, the rising interest rates of central banks battling unprecedentedly high inflation is providing wealthier households with a solid additional return, which ceteris paribus reduces their propensity to consume. Households can use higher savings to pay off their debt more quickly (cf. the ongoing refixing of mortgages in an environment of significantly higher interest rates) or to make new investments. Investments can be directed at mitigating the impacts of the growth in energy prices (insulating homes to make them more energy efficient) or at procuring personal or more cost-effective sources of energy (small solar power plants and heat pumps). Last but not least, according to Ricardian equivalence, households may save more in anticipation of future tax increases, as much of the macroeconomic stabilisation during the pandemic was done through fiscal transfers, at the cost of growth in sovereign debt.

Concerns about the energy crisis boosted saving rates again in many euro area countries

Euro area economies suffered another shock when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The invasion exacerbated the inflationary pressures by causing a sharp rise in prices of energy, especially electricity and gas. The real income of euro area households dropped markedly and there were growing concerns about energy expenditure as the 2022/2023 heating season – the first without gas supplies from Russia – drew near. Although countries found replacement supplies mainly from Norway and the USA, they did so at the cost of a surge in prices for both firms and consumers.

Households’ demand for energy is inelastic in the short run. So, households can respond to sharp growth in energy prices by: (i) reducing their consumption of non-energy goods and services, (ii) reducing their propensity to save, or (iii) increasing their income. Most euro area households did not reduce their propensity to save. As Chart 1 shows, the saving rate of euro area households actually increased at the turn of 2023. Households in Germany saved only slightly more, while the saving rate in Spain soared again. Unlike in the pandemic period, the rise in the saving rate during the energy crisis was due mainly to precautionary motives. Households also made energy savings, consuming less gas not only because of the mild winter, but also at the cost of lower thermal comfort.

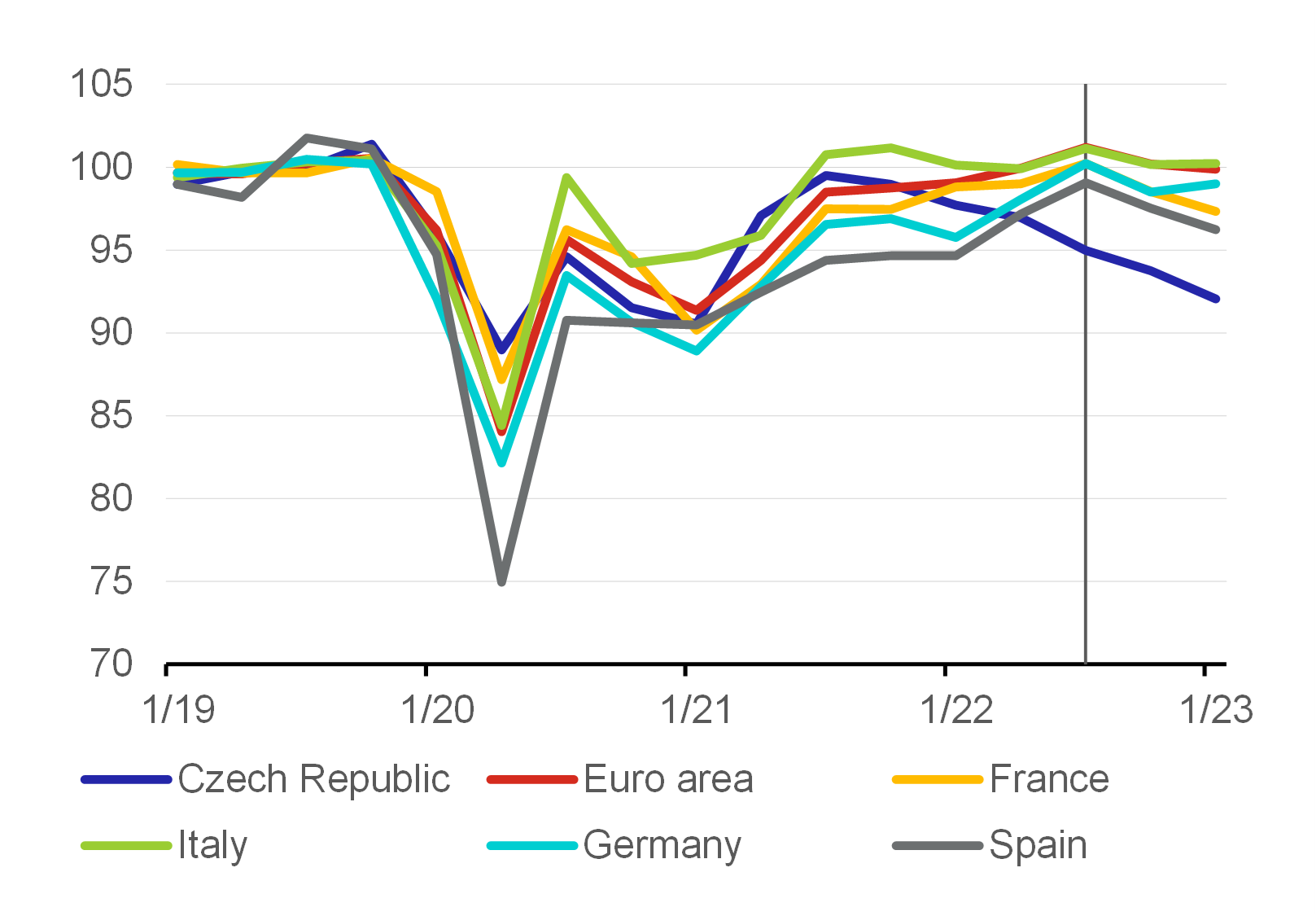

European households thus did not reduce their propensity to save in order to offset falling real income. Gradually rising interest rates in the euro area also fostered a higher saving rate. At the same time, most euro area countries introduced measures to protect households against energy poverty (such as caps on energy prices in Germany, France and the Netherlands). This reduced the magnitude of the price shock for households. By contrast, households seem to have responded to the energy crisis primarily by reducing their real consumption amid surging consumer inflation. Chart 2 shows the decline in household consumption in the large euro area economies over the last two quarters (the grey area). However, the decline was smaller than that in the Czech Republic, where household consumption dropped to the 2021 Q1 level in real terms.

Chart 2 – Household consumption

(index 2019=100)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Black line represents the beginning of energy crisis period. Constant prices, seasonally adjusted.

Czech households spent less and saved more by European comparison

The international comparison thus shows considerable similarity in households’ responses to the energy crisis –real consumption is falling in most countries due to rising inflation amid higher-than-usual saving rates. However, this effect is very strong for the Czech Republic. At the end of 2022, the Czech saving rate neared levels typical of the traditionally very thrifty Germany, exceeding 18%, and in 2023 Q1 it fell only slightly. It is thus around 6 pp above the 2011–2018 average. Household consumption conversely dropped very dramatically in real terms. Not only did Czech households save more on average amid declining real income, but the purchasing power of their income also dropped rapidly. The shifts in Czech households’ consumption and saving are larger than those in the euro area economies, especially in 2023 Q1 (see Chart 3). In addition to precautionary motives, this can be explained by the substantially higher Czech interest rates.

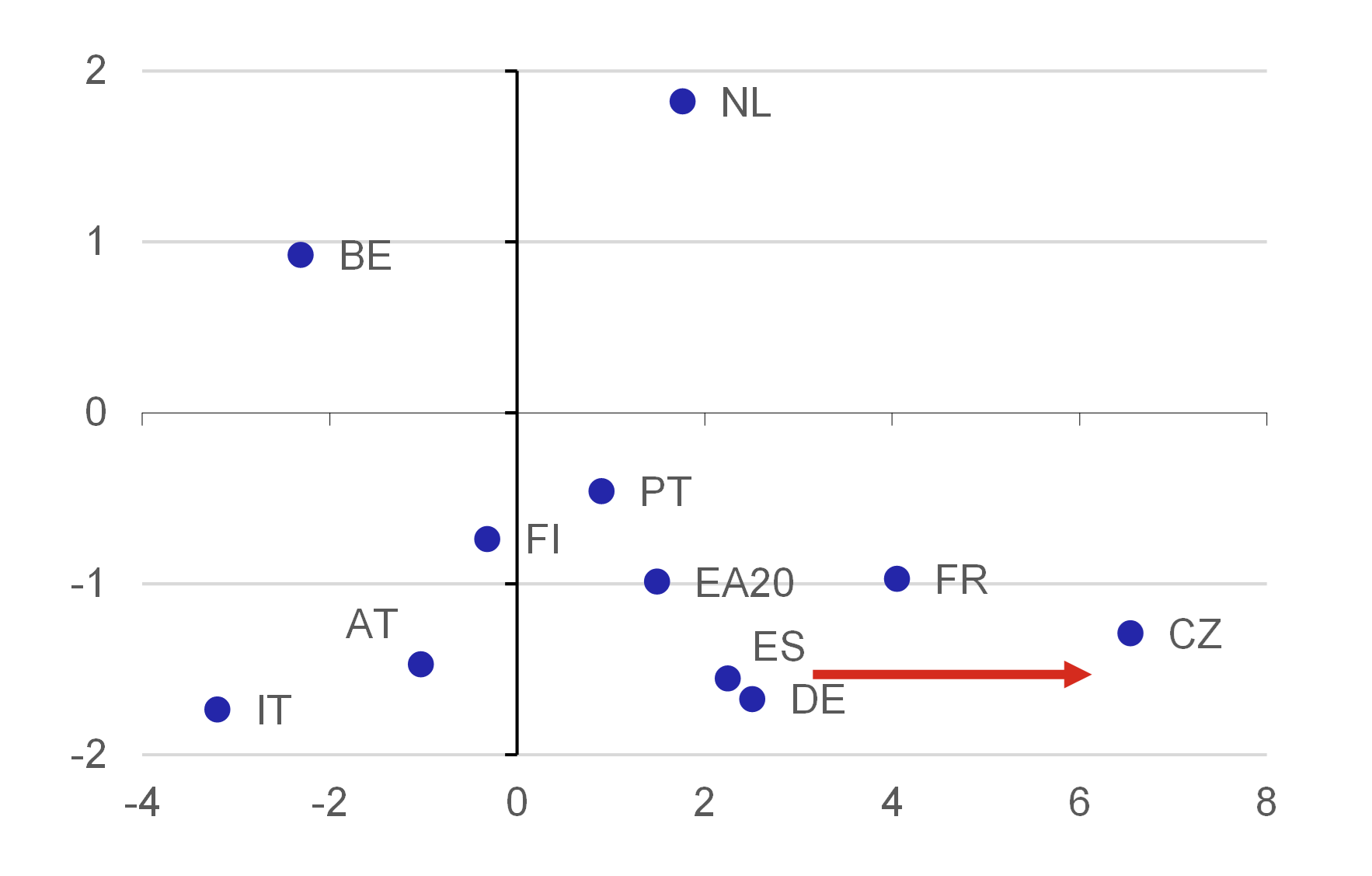

Chart 3 – The saving rate versus consumption in 2022 Q4

(y-axis: Y-o-y household consumption growth in %; x-axis: Deviation of saving rate from 2011-2018 average in pp)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Austria – AT, Belgium – BE, Finland – FI, France – FR, Germany – DE, Italy – IT, Netherlands – NL, Portugal – PT, Spain – ES, euro area (20 countries) – EA20, Czech Republic – CZ.

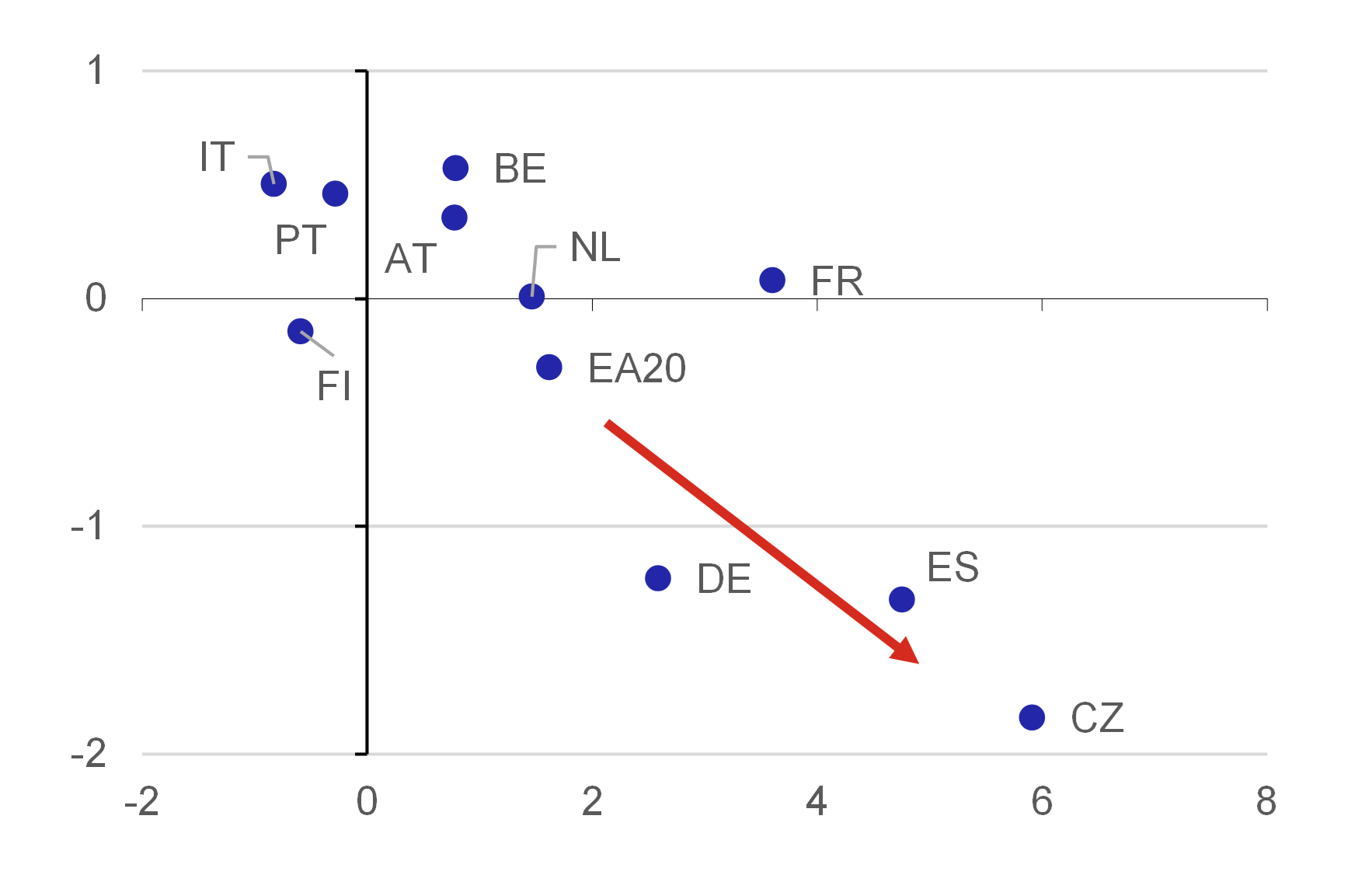

Chart 4 – The saving rate versus consumption in 2023 Q1

(y-axis: Y-o-y household consumption growth in %; x-axis: Deviation of saving rate from 2011-2018 average in pp)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Austria – AT, Belgium – BE, Finland – FI, France – FR, Germany – DE, Italy – IT, Netherlands – NL, Portugal – PT, Spain – ES, euro area (20 countries) – EA20, Czech Republic – CZ.

Where have euro area households channelled their savings over the last three years?

If European households saved more and consumed less during both the pandemic and the energy crisis, the question is where did they channel their savings? The precautionary motives speak mainly in favour of purchases of various financial assets, especially liquid ones. However, households may have used used part of the money to invest in housing – to purchase or renovate property. Mortgage rates were low in the euro area during the pandemic, but the ability to trade in property was limited during the lockdowns.

The gross household investment rate in the large euro area economies rose only modestly during the pandemic (see Chart 5) and fell slightly at the turn of 2023. The investment rate in the Czech Republic started to fall noticeably in late 2021, hence Czech households did not use their higher propensity to save to such an extent as to increase their tangible (fixed) investments.[4] This again supports the hypothesis of a preference for higher-yielding financial assets in an environment of rising interest rates.

Chart 5 – The household gross investment rate

(in %)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Seasonally adjusted.

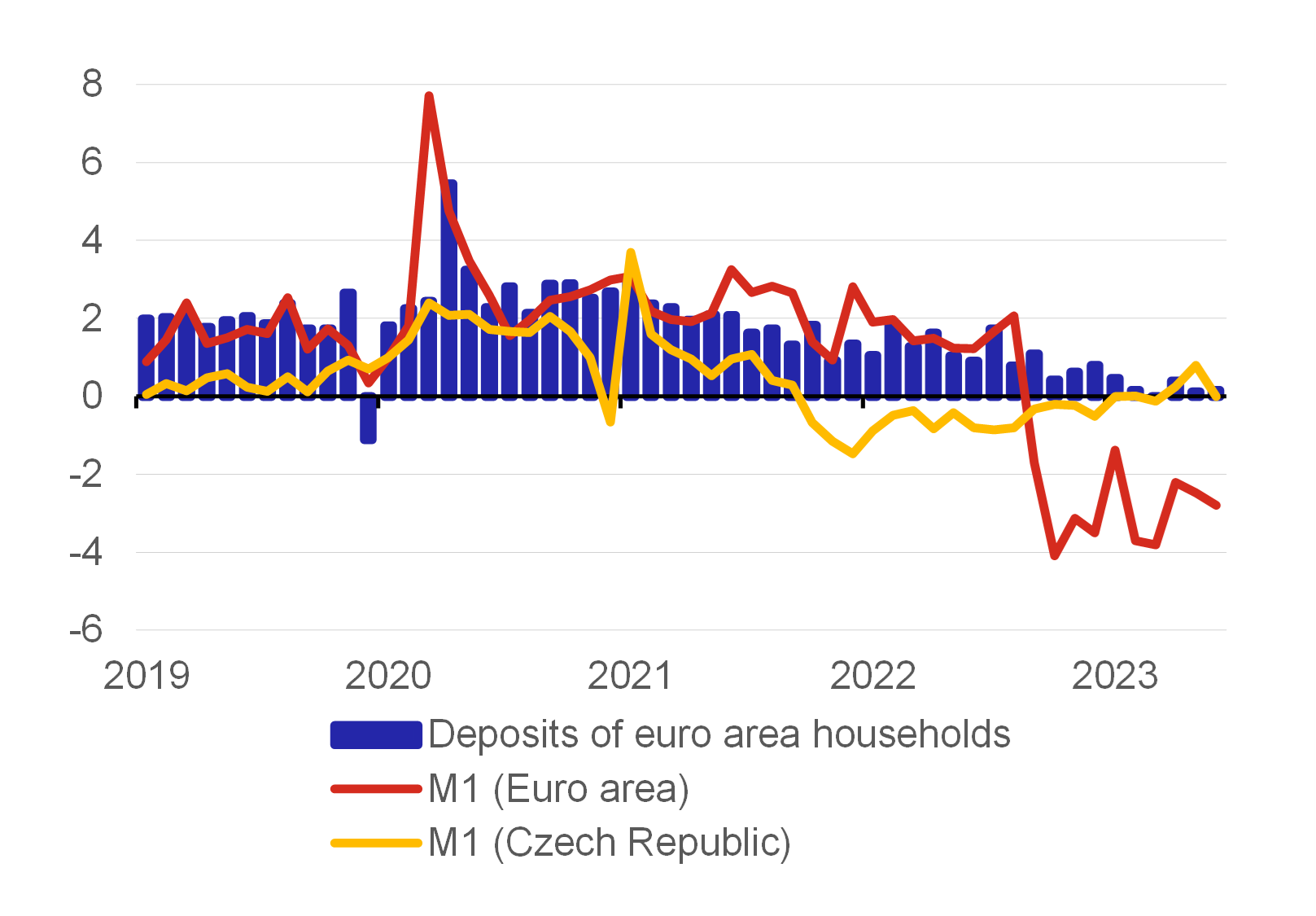

By contrast, the deposits and loans of euro area households rose sharply during the first wave of the pandemic (see Chart 6). Growth in deposits would imply greater interest of households in more liquid assets than fixed assets. This trend reversed in the second half of 2022 after the European Central Bank raised interest rates for the first time since the financial crisis and started its relatively drastic tightening cycle.[5] Gradual transmission from policy rates to financial market yields then stimulated an outflow of funds into higher-yielding assets. A relative decline in the most liquid assets (M1) was also fostered by other central bank operations (a halt to reinvestment under the asset purchase programme and repayment of longer-term refinancing operations programmes). The Czech monetary aggregates data suggest a similar trend,[6] although the rate-raising cycle started to have an impact earlier.

Chart 6 – Household deposits and monetary aggregates

(monthly changes in ratio of deposits to gross disposable income; index for M1; January 2020 = 1; seasonally adjusted)

Source: ECB, CNB

Note: Seasonally adjusted.

Households’ current high propensity to save has thus not been redirected into an increase in the fixed investment rate to any significant extent, so households may in time return to their pre-crisis shopping and current expenditure behaviour. The reasons to panic vanished and the precautionary motive to save more is disappearing, but the increased interest rate level will hinder the return to usual consumer behaviour in the quarters ahead. Interest rates in the euro area were last at the current level at the height of the GFC. Financial markets do not expect euro area rates to start decreasing before mid-2024, while analysts are predicting that monetary policy in the Czech Republic will begin to be eased as early as this year. The current propensity to save is exceptionally high in the Czech Republic. A decline to its long-term average could lead to stronger and earlier stimulation of consumption than in most euro area countries.

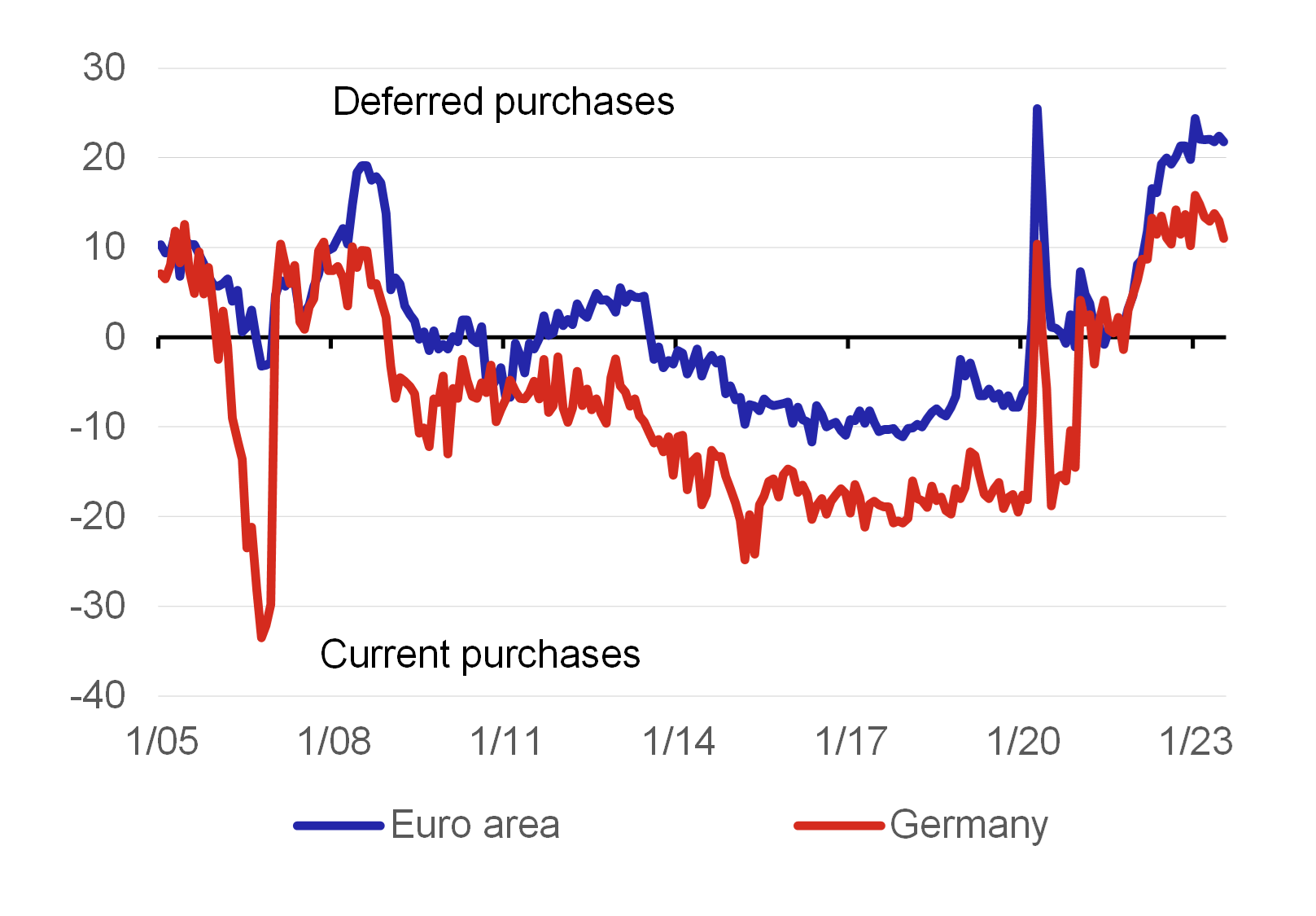

For the time being, though, there are no signs of a turnaround in household sentiment. Some evidence is offered by data from a survey of German households[7] available in the data for the Economic Sentiment Indicator (ESI). After the pandemic lockdowns, German households preferred to make major purchases and draw on their savings (see Charts 7 and 8), but in 2022 Q1 their sentiment changed and consumers started to postpone their plans to make major purchases. Their preference to save increased as well.

Chart 7 – Purchases by German households

(pp; intentions, next 12 months)

Source: Eurostat, European Commission (ESI)

Note: Difference between the ESI indicators “Major purchases over the next 12 months” and “Now is the right moment to make major purchases”, so a positive value indicates a preference for future purchases and a negative value a preference for current purchases.

Chart 8 – Savings by German households

(pp; intentions, next 12 months)

Source: Eurostat, European Commission (ESI), data not available for euro area

Note: Difference between the ESI indicators “Savings over the next 12 months” and “Now is a good moment to save”, so a positive value indicates a preference for future savings and negative value a preference for current savings.

Conclusion

The household saving rate varies historically across countries, and the Covid-19 pandemic increased it significantly. The saving rate rose most of all during the Covid-19 pandemic, not only in Europe, but also in the USA and Japan.[8] During the lockdowns, the elevated saving rate was mostly forced, since households could not spend on goods and services. A strong fiscal stimulus was implemented at the same time.

After the pandemic ended, Europe was hit by another crisis, this time an energy crisis. This crisis also affected the household saving rate, but the response varied from country to country. Unlike in the pandemic period, the rise in the saving rate during the energy crisis was due mainly to precautionary motives. This effect was particularly strong in the Czech Republic, where the saving rate in late 2022 neared the levels typical of the traditionally very thrifty Germany.

Interest rates in the euro area have been raised significantly over the last year, and this is starting to be reflected in households’ behaviour and a higher preference to save. In the years ahead, the increased interest rates will hinder the decline in households’ propensity to save. In the near future, higher interest rates may support the willingness to save in the near future in the euro area, where the policy thightening cycle is peaking only now.

Written by Soňa Benecká and Luboš Komárek. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Czech National Bank.

References

Attinasi, M. G. – Bobasu, A. – Manu, A. S. (2021): The implications of savings accumulated during the pandemic for the global economic outlook. ECB Economic Bulletin, 5/2021 https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2021/html/ecb.ebbox202105_01~f40b8968cd.en.html

Benecká, S. (2022): How have firms’ price increases contributed to the current inflation in the euro area? Global Economic Outlook https://www.cnb.cz/export/sites/cnb/en/monetary-policy/.galleries/geo/geo_2022/gev_2022_09_en.pdf

Benecká, S. – Kábrt, M. – Komárek, L. – Polák, P. (2023): Do the breadth and intensity of the tightening of monetary conditions affect their impact on the global economy? Global Economic Outlook https://www.cnb.cz/export/sites/cnb/en/monetary-policy/.galleries/geo/geo_2023/gev_2023_01_en.pdf

Dossche, M. – Zlatanos, S. (2020): COVID-19 and the increase in household savings: precautionary or forced? ECB Economic Bulletin, 6/2020 https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2020/html/ecb.ebbox202006_05~d36f12a192.en.html

Dossche, M. – Krustev, G. – Zlatanos, S. (2021): COVID-19 and the increase in household savings: an update. ECB Economic Bulletin, 5/2021 https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2021/html/ecb.ebbox202105_04~d8787003f8.en.html

Abdelrahman, H. – Oliveira, L. E. (2023): The rise and fall of pandemic excess savings, FRBSF Economic Letter, 2023-11 https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2023/may/rise-and-fall-of-pandemic-excess-savings/

Keywords

Saving rate, investment rate, pandemic, energy crisis

JEL Classification

D14, E21, E43

[1] The Czech saving rate is discussed by Michálek and Šarboch in Reasons for households’ current increased propensity to save.

[2] The dominant effect of forced savings during the first wave of the pandemic is confirmed by several studies, for example Dossche and Zlatanos (2020) and Dossche, Krustev and Zlatanos (2021).

[3] See Attinasi, Bobasu and Manu (2021).

[4] However, caution is warranted when interpreting saving rate data, as the time series are subject to major revisions. Previous estimates tended to indicate a flat investment rate in the Czech Republic.

[5] See Benecká, Kábrt, Komárek and Polák (2023).

[6] The Czech M1 time series is slightly distorted at the end of 2021 because the seasonal adjustment method has difficulty identifying effects relating to banks’ contributions to the guarantee system, which vary in strength from year to year.

[7] Indicators are available for more countries, but for methodological reasons their information value is not high and they are more difficult to compare across countries.

[8] See the chart in the April 2023 issue of Global Economic Outlook.