Unemployment in the euro area: Why is it so low and when will it start to rise?

The economic situation in the euro area has not exactly been dazzling recently. Output is stagnating – production is being dampened by weakening external demand, and investment is being adversely affected by tightened monetary policy. Since the services sector has also weakened, the only admirable area of the economy remains the strong labour market. This article maps out, from various perspectives, the causes of the current record-low unemployment in the euro area. It discusses both cyclical and structural factors, and also provides a glimpse below the surface of the overall figures, focusing on the diverse developments across Member States. At the same time, it notes the emerging signs of an incipient cooling of the labour market in the euro area, now at a turning point. It therefore does not neglect estimates of near-term future developments.

Miracle: Never before have so few people been out of work in the euro area

The unemployment rate has now stayed at a record low for six months. Since the creation of the euro area, it has never been as low as in recent months, when it has fluctuated at around 6.5%[1] (see Chart 1). This may not seem such an exceptional figure at first glance, especially given that the unemployment rate in the United States has been below 4% for several years and is not even 3% in Japan. However, it is an unprecedented success for the euro area, especially for those countries that have battled unemployment for many years.

Chart 1 – Unemployment rates across euro area countries

(%, seasonally adjusted)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Chart depicts the evolution of unemployment rate in euroarea and each of their 20 members; selected countries are highlighted.

The aggregate euro area figure masks the significant heterogeneity across the Member States. Spain has had the highest unemployment rate for more than a year. It was closely followed by Greece, which dominated the ranking for most of the last decade. The unemployment rate remains at double digits in both countries, 12% in Spain and 10% in Greece. At the other end of the spectrum, Germany has a 3% unemployment rate, and Malta, especially in recent months, is even slightly lower.

The recent decline in the unemployment rate to its current historical lows in the euro area is mainly due to a significant improvement in the situation in Greece and, in particular, in Spain, with its large population. Ten years ago, unemployment stood at over 25% in both these countries. One in four people of working age who wanted to be employed could not find work. Since then, however, unemployment in these countries has been steadily and significantly declining (except for a small break at the beginning of the COVID pandemic). Similarly, although from a much lower unemployment base, this has also been the case in Portugal, Cyprus and Croatia. However, given their small populations, the impact of these last two countries on the euro area aggregate was much smaller. With the exception of Italy, the southern periphery of the euro area is experiencing a great period. These economies have posted the highest year-on-year economic growth of any euro area country.[2] One definite reason for this is the fact that they were generally significantly less impacted by last year’s energy crisis than their more northerly neighbours.

There has thus been clear convergence in unemployment rates among the Member States over the last ten years. In September 2013, at the time of the debt crisis, the difference in unemployment rates between the hardest-hit Greece and Germany at the other end was more than 23 percentage points, and the standard deviation exceeded 6 pp. Currently[3], Spain and Malta are separated by only 9 pp. At the same time, the standard deviation has fallen to 2.2 pp. This is great news for the monetary union, because the more homogeneous it is, the easier it will be to find the optimal economic policy settings. However, it is still far from ideal and is not even close to its best moments in this regard. In the spring of 2008, before the outbreak of the global financial crisis, the difference in the unemployment rates between the worst-performing Slovakia and the best-performing Cyprus was less than 7 pp, and the standard deviation decreased until August 2008, when it was only 1.9 pp. Nevertheless, the period of convergence or divergence of unemployment rates among euro area countries mainly reflects the significantly higher volatility of this statistical variable in some euro area economies.

How is it possible that unemployment is not rising in the current difficult economic situation?

The last three years can hardly be characterised as a particularly bright period for the euro area economy. After some relatively successful years, it began to run out of steam in 2019. The difficulties of the low-performing industrial sector were puzzling. Yet it still had no idea that the COVID pandemic, the associated supply-chain problems and, on top of all that, the energy crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine were on the way. These three horrors brought huge supply-side inflation pressures and, together with the demand pressures stemming from the savings accumulated during the COVID pandemic, catapulted consumer price growth in the euro area to unprecedented heights.

However, in the flood of bad news and pessimistic sentiment, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that not much actually happened. The euro area’s gross domestic product returned to its pre-pandemic level as early as in the third quarter of 2021 and then continued to grow quite well until last autumn. The European Central Bank, the euro area governments and the European Union reacted very quickly to the recent crises and with great vigour. Both monetary and fiscal policies were loosened in an unprecedented manner, and only history will show whether this was too much in some cases. Active economic policy thus sustained the euro area at the right time and did not let normal economic operations fall by the wayside.[4] The potential consequences of economic stagnation in 2023 will only appear in the labour market with a lag due to the usual delays. Nevertheless, GDP has not yet declined significantly, and there is therefore no reason to lay off too many workers yet.

We have not seen wild waves of company bankruptcies causing queues at labour offices. On the contrary, during the COVID pandemic, the number of euro area legal persons that commenced bankruptcy[5] proceedings fell sharply (by almost half) and only very gradually returned to their long-standing usual levels (see Chart 2). These did not reach this level until the end of last year. However, growth in the number of new bankruptcies picked up somewhat this spring (to 9% quarter-on-quarter). This growth is being driven mainly by Spain, where the number of bankruptcies has risen sharply every quarter since the summer of 2020 and has roughly tripled compared to the pre-COVID level (see Chart 3). The increasing number of bankruptcies is not only a problem in Spain, but in no other country has it been nearly as pronounced. For example, Germany and Italy have not yet reached their pre-COVID bankruptcy levels.

Chart 2 – Bankruptcies and registrations of new firms in the euro area

(index, 2015=100)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Seasonally adjusted.

Chart 3 – Bankruptcies across selected euro area countries

(index, 2015=100)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Seasonally adjusted.

The number of bankruptcies of firms in services is growing in particular, while industrial firms appear resilient. Looking at the sector structure of bankruptcies in more detail, it is clear that more and more transport and storage operations are disappearing in the euro area, followed by accommodation and food service activities (see Chart 4). The beginning of this trend coincided with the outbreak of the pandemic, yet did not stop after it subsided and was actually encouraged by last year’s energy crisis. This spring[6], almost twice as many firms from the above two service sectors declared bankruptcy than was normal before COVID (autumn 2019). By contrast, although the number of bankruptcies in industry is rising slightly, they remain around 15% below the pre-COVID level.[7]

Chart 4 – The sectoral structure of bankruptcies in the euro area

(index, 2015=100)

Source: Eurostat

Note: Seasonally adjusted. Structure according to the economic activities NACE Rev. 2. The original codes are as follows: B-S_X_O_S94, B-E, F, G, H, I, J, K-N, P-S_X_S94.

Bankruptcy alone may not be a problem for the labour market if enough new firms are being created at the same time. In the case of creative destruction, this would even be a welcome step forward. The number of newly registered legal persons in the euro area has been rising steadily, with the exception of the break during the pandemic (see Chart 2).[8] Thus, until recently, the overall situation of the corporate sector did not appear to have deteriorated significantly in this respect. At the start of this year, the creation and dissolution of firms was still balanced. In the first quarter of this year, 7% more new companies were registered than at the end of 2019. The situation was similar for bankruptcies. However, their rapid quarter-on-quarter growth this spring draws attention to the topic of the pace of closure of operations.

The sharp increase in corporate profit margins has also contributed to the absence of reasons for dismissal.[9] Profit margins have been exceptionally high in the euro area over the past three years, making them a useful medium-term buffer for firms.[10] They can thus very well enable firms to retain existing staff during a period of substantial economic uncertainty. However, this buffer will not last indefinitely. On the contrary. The ECB’s September macroeconomic forecast assumed that the unit profit of euro area firms had already declined in the second half of this year, and this situation was expected to persist until the summer of 2024.

Another reason why the unemployment rate is not inclined to rise is labour hoarding. This is a well-described economic phenomenon where firms are not willing to reduce employee numbers even in a situation where their production is falling. There are many rational reasons for such hoarding. The fixed costs of hiring and firing themselves are significant, and there is also the fact that for a long time the productivity of a new employee may, depending on the nature of the work done, be lower than that of their experienced colleagues. The tendency for labour hoarding is particularly high in periods of tight labour market conditions. Firms are aware that if they need to re-hire an employee, it will be very difficult to do so and so they prefer to keep their existing workforce as long as they can. With labour demand in terms of job vacancies still near record levels in the euro area, reluctance to lay off workers remains understandably high. A similar picture is offered by the European Commission’s regular survey of companies asking about the factors limiting their production. It shows that while labour shortages were an obstacle for around 15% of them in the euro area before the pandemic, today, despite a certain decline in the past year, this is a problem for almost a quarter of respondents in industry, while no less than one in three firms in services are struggling with a shortage of people (see Chart 5). Of course, the situation is much worse in the economies with the lowest unemployment rates. A survey by the German Ifo Institute[11] shows that as many as half the country’s companies in the service industry and a third in manufacturing are affected by the shortage of skilled labour.[12]

Chart 5 – The labour force as a factor limiting production in the euro area

(%, s. a.)

Source: European Commission – Business and consumer survey

Note: Firms may give more than one factor in their response.

Or is it not so miraculously low after all?

At the same time, the labour market is undergoing deeper structural changes. The current record-low unemployment rate in the euro area is thus not necessarily linked solely with the position of the euro area economy in the business cycle. On the contrary. Labour market developments very often reflect deeper structural changes over time in society. From this perspective, the current situation may not seem so striking.

More and more people are employed in the euro area, but they are working less. The employment rate in the euro area has been rising over a long period.[13] The share of workers in the total population rose from 68% to 72% between 2010 and 2019. Although a downturn due to the pandemic followed, this was quickly offset and employment indicators are now close to 75%. And this is not due to a fall in the labour force: the participation rate in the euro area is also steadily increasing.[14] At the same time, however, the average number of hours worked per person employed is falling in parallel. According to Botelho et al. (2021), the decline in the euro area was 2.5% between 2010 and 2019. There was a short-term sharp fall with the advent of the coronavirus, but it then quickly recovered and subsequently, as Arce et al. (2023) show, it stabilised at around 1.5% below the pre-COVID level. Both trends – the rise in the employment rate and the reduction in average working hours – are evident across euro area countries, yet there are significant differences in the levels common in each country. However, there is a clear inverse proportion: countries with lower employment rates tend to have higher average working hours. The employment rate in the euro area, as expected, is the lowest in Italy (66%), followed by Greece and Spain. By contrast, it exceeds 80% in the Netherlands and Germany.[15] Botelho et al. (2021) show that the number of hours worked per worker in Germany is about one-fifth lower than in Italy and Spain, while France remains roughly in the middle and close to the levels for the euro area as a whole in terms of both employment rate and average hours worked.

The reasons for the falling average hours worked vary. For a part of workers, lower working hours reflect a shift in preference from work towards free time. For others, the increasing willingness of employers to offer part-time work is their ticket to enter the labour market (e.g. for carers and people with disabilities) as they would not be able to work full-time. This is confirmed by an analysis by Botelho et al. (2021), which concluded that the main factor behind the long-term (based on the analysis of data from 1995–2019) decline in the average number of hours worked per worker in the euro area was the increase in women’s labour market participation rate. They identified, as another structural cause, a decrease in the proportion of self-employed people among workers, as they have on average higher numbers of hours worked per person than regular employees. However, there remains a certain proportion of workers who, on the contrary, work part-time involuntarily and would actually like to spend more hours at their jobs. However, the significance of this mismatch in the euro area is diminishing over time (and with rising labour market tightness). There is a phenomenon behind the lower average number of hours worked per worker, especially recently, that is completely outside the above-mentioned range of longer-term factors: higher sickness rates in the sense of people taking time off for health reasons. Arce et al. (2023) report that the use of sickness benefits in the largest euro area countries increased by between 10% and 30% between 2021 and 2022.[16]

The low unemployment rate may thus reflect the increasing inclusiveness of the euro area labour market. We can, with slight exaggeration, perceive it as a consequence of the gradual shifting of roles in society, when instead of the previously common division of the population into those who formally work and those who do not, society increasingly prefers a situation in which as many of its members as possible can work, at least to a certain extent. This topic combines a number of modern phenomena that could be summarised more generally under the concept of increasing inclusion. The changing form of economic activity and the ever-new technical achievements are bringing the possibility of including in the work process those who in the past remained outside it. The long-term shift of employment from agriculture and industry to the services sector, coupled with the ongoing digitalisation across economic sectors, have enabled changes in the organisation of work. Part-time work or remote work have thus become common in many fields without major problems. This means that, for many people, participation in the labour market is no longer the challenge of: ‘either – or’, but rather ‘how much’. The employment rate of women in general and older people is increasing. Paid activity can also be more easily pursued by people who take care of someone or those whose state of health would not allow them to work full-time. This makes it easier for those looking for a job to find one that matches their limitations. Society is emphasising a reconciliation of the private and professional life and is seeking to break down the remnants of discriminating restrictions, and is thus moving closer to full employment.

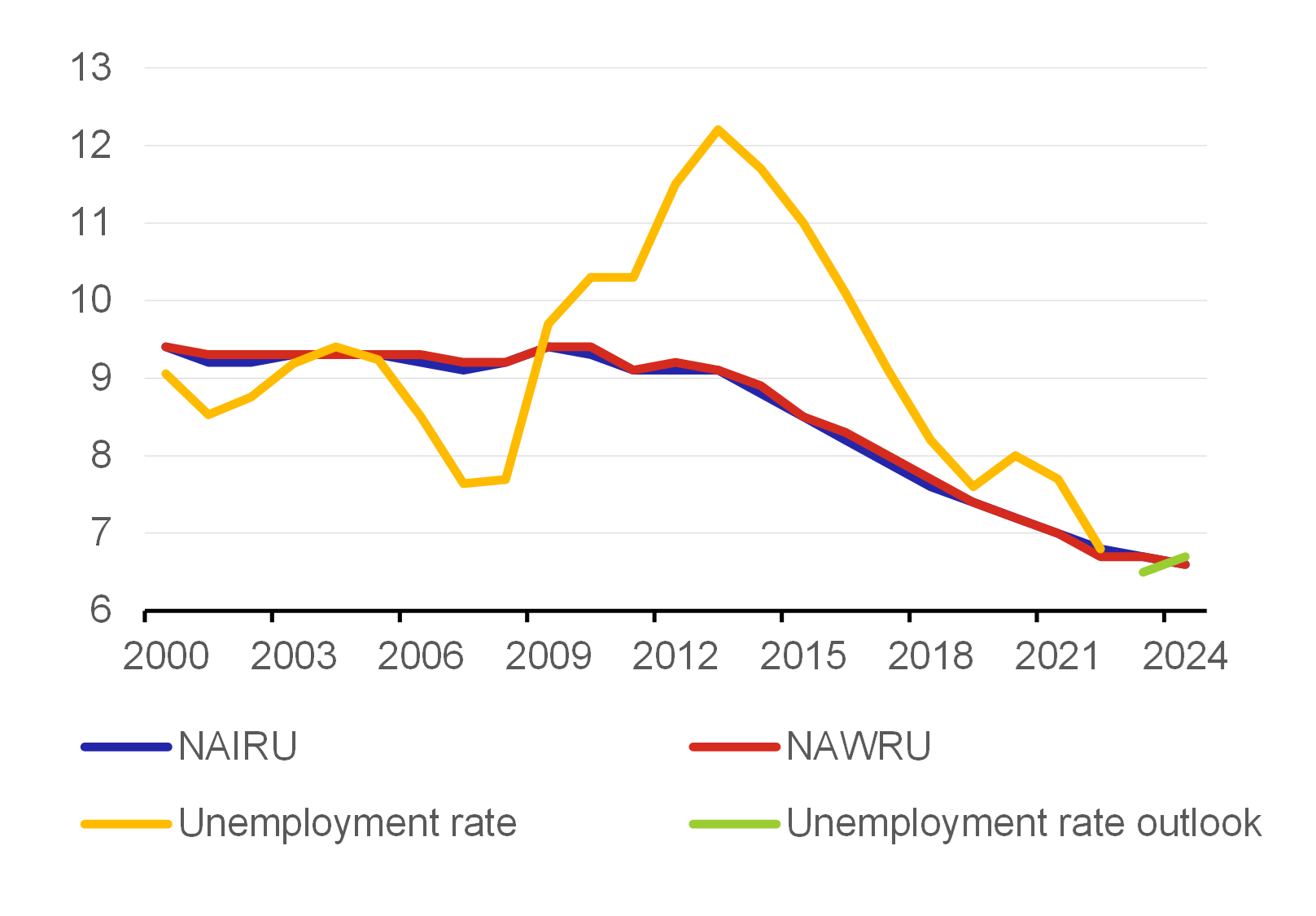

In line with this, the equilibrium unemployment rate estimates in the economy are also falling.[17] This can be illustrated by the NAIRU – the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment.[18] To estimate this type of structural unemployment, the relationship between the change in the unemployment rate and inflation (the Phillips Curve) is used, or a modification replacing consumer inflation with wage inflation (in accordance with the original idea described by W. H. A. Phillips). The NAWRU – the non-accelerating wage (inflation) rate of unemployment – is then used for this. The available estimates of the NAIRU and the NAWRU for the euro area show that between 2000 and 2013 the equilibrium unemployment rate hovered slightly above 9% and, despite its slightly downward trend, was surprisingly stable over time[19] (see Chart 6). After the debt crisis in the euro area faded, the equilibrium unemployment rate began to fall systematically.

Chart 6 – Equilibrium unemployment rate in the euro area

(%)

Source: European Commission – AMECO, Oxford Economics, Eurostat, Consensus Forecast

Note: Annual data.

This can be attributed to a gradual easing of the relationship between unemployment and wage growth. This may be a manifestation of employees’ diminishing bargaining power in the face of monopsony demand from employers, as reported by Blanchflower and Bryant (2019). However, it is affected by a wide range of factors, including slowing labour productivity growth, population ageing and many institutional[20] and technological factors that lead to a reduction in labour market rigidity and facilitate the matching process between labour supply and demand. This also applies to the trend towards increasing inclusiveness in the euro area labour market described above. However, the fall in the equilibrium unemployment rate over the last ten years has also been a reflection of the observed hysteresis in the labour market.[21] According to this theory, a change in the unemployment rate results in a change in its neutral rate in the same direction with the passage of time. At the same time, Ball and Onken (2021) showed, in a sample of 29 OECD countries, that this relationship is stronger when unemployment falls than when it rises.

The euro area unemployment rate is currently only slightly below its estimated equilibrium level. The latest available NAIRU and NAWRU forecasts for the euro area estimate the equilibrium unemployment rate for this year at 6.7%. So far, however, the average unemployment rate[22] this year has been 6.5% in the countries that use the euro. However, it would be risky, or at least premature, to draw conclusions from this about inflation pressures stemming from the labour market. The NAIRU concept was actually initially used to analyse sources of inflation pressures. Over time, however, a number of empirical studies have pointed out that NAIRU estimates are highly inaccurate and that the degree of uncertainty about the accuracy of the estimate increases towards the current point in time. Comparing the latest data on the unemployment rate with the NAIRU estimates for the same date may therefore be highly misleading.[23] Thus, the usefulness of NAIRU estimates now lies primarily in the fact that they provide information on longer-term trends in the unemployment rate. As a result, the fact that the unemployment rate in the euro area is now close to the NAIRU and NAWRU estimates can be interpreted as meaning that, despite its record low level, it may not be “unhealthily” low unemployment but rather a kind of new normal that is more or less in line with the equilibrium state.

No major imbalances are apparent across the euro area countries. In most Member States, the average unemployment rate in 2023 has not significantly deviated from the NAWRU level predicted for them this year (see Chart 7). In only five economies does the gap between the unemployment rate and the NAWRU reach more than one percentage point. The unemployment rates in Slovenia, Cyprus and Italy are more markedly below the estimated equilibrium level. By contrast, only Greece and Spain remain above it, with the estimated NAWRU in the former having been very stable (around 10%) over the last ten years while falling by almost a third in Spain over the same period.

Chart 7 – Unemployment vs the NAWRU in the euro area – 2023

(%; x-axis: 2023 average unemployment, y-axis: NAWRU 2023 prediction)

Source: European Commission – AMECO, Eurostat

Note: Values for every eurozone member is depicted; selectd countries are highlighted.

Will it rise or not? That’s the question!

The euro area is unlikely to enjoy its record-low unemployment levels for very long. A more detailed look at developments in individual countries shows an increasing tendency to reverse the trend. Unemployment rates have now been rising for some months in the Baltic states, Luxembourg and Austria. Less significant increases have been recorded in Finland and the Netherlands. With the exception of Estonia, however, the increases have been rather modest so far. This should also be the case in the near future for the overall figures for the euro area, which are expected to rise only by tenths of a percentage point. In its September projections, the ECB estimated that the unemployment rate would reach 6.7% next year and remain at that level in 2025. The CF[24] respondents’ outlook expects the same figure for 2024.

The observed fall in demand for labour also suggests more about the future development of unemployment. The fall in the unemployment rate in the euro area has been accompanied by a fall in job vacancies for several quarters (see Chart 8). Looking at the Beveridge curve, which illustrates the relationship between unemployment and the number of job vacancies, it seems that the previous upward movement to the left in the chart, corresponding to a theoretical movement along the curve, symbolising a cyclical shift in terms of an improving economic situation, has been replaced by a downward movement to the left, which is interpreted in theory as a structural shift towards greater labour market efficiency.[25] In practice, however, this may not be so black and white, especially in the short term. From the employer’s point of view, if the economic situation deteriorates, it is rational to first withdraw its offer of job vacancies and only then proceed with redundancies, which would be reflected in an increase in unemployment. Thus, a short-term downward movement within the Beveridge curve chart may indicate, instead of a structural shock, an approaching turning point in the movement along the curve in the opposite direction.

Chart 8 – Beveridge curve

(%)

Source: Eurostat

Note: x-axis: unemployment rate; y-axis: share of unfilled vacancies.

The share of vacancies has been falling mainly in the north-westerly part of the euro area for some time now. In Germany, the share of vacancies fell from 4.6% to 4.1% between the middle of last year and the middle of this year,[26] with a simultaneous fall in the absolute number of vacancies and an increase in the number of positions filled. Similarly, albeit to a slightly lesser extent, the share of vacancies also fell in the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Luxembourg and Ireland. Finland has recorded a sharper fall in demand for labour. By contrast, the countries of the euro area’s southern flank are not yet following a similar trend. In Spain, demand for labour remains stable, in Greece it is growing steadily, and Italy is also still on a growth trend. However, the vacancy rate in all these economies is significantly lower than in Germany, Austria, Belgium or the Netherlands, where it remains well above 4%. Overall, the Beveridge curves suggest that as long as employer optimism persists in southern Europe and the supply of new jobs tends to grow, the overall unemployment rate in the euro area cannot be expected to increase dramatically, despite its gradual increase in many countries further north.

Conclusion

The current record-low unemployment rate in the euro area is due to many factors. From a regional perspective, it is mainly due to the current economic resilience of the southern flank of the euro area (with the exception of Italy). These economies have been much less affected by the energy crisis than the industrialised countries of Central and Western Europe, led by Germany. This has led to a convergence of unemployment rates across euro area countries, with unemployment rates falling in the countries with the highest unemployment rate levels, while unemployment in countries at the other end of the spectrum has recently tended to turn towards moderate growth. The evolution of the overall unemployment rate in the euro area will depend to some extent on which trend prevails in the near future. Particular attention should be paid to the current driver of the fall in unemployment in the euro area – Spain – where the fall in the unemployment rate has stopped in recent months, as has growth in demand for labour, and where the rate of growth of bankruptcies is accelerating.

The last two shocks – COVID and the war in Ukraine – were not of economic origin and, given their size, required significant policy interventions that shook the established paradigms of the business cycle. Paradoxically, the series of negative external supply shocks did not lead to such a serious increase in unemployment in the euro area as could have been expected if the responsible institutions had not been so active. This was not just a case of “kurzarbeit” measures. Rescue programmes prevented a wave of corporate bankruptcies that would otherwise have been likely to occur. It should be noted that none of this was for free. The smoothing out of the cyclical slump was done, and not only in the euro area, using debt.[27] Another specificity was that the inflationary tsunami caused by the explosion in energy commodity prices tended to sweep away consumers, while many producers rode the wave as they were able to increase their profit margins. However, the war in Ukraine has also affected the euro area labour market in other ways. The Member States, led by Germany, have accepted a significant number of refugees into their territory in a short period of time. However, it seems that the exceptionally tight labour market may able to absorb them.[28]

At the same time, the euro area labour market is going through gradual structural changes. These are also changing the normative perception of how low the unemployment rate can be while still benefiting the economy, or when concerns about the excessive overheating of the economy are appropriate. The current level of unemployment appears to be close to its equilibrium level estimates and should not pose a threat to the euro area. There is still room for a further fall, especially in some countries. In others, the situation is tighter. At the same time, in countries with very low unemployment, there is a shortage of skilled labour. This structural mismatch between demand and supply could be at least partially reduced by the ongoing technological developments that could help address the lack of human capital. Rationalisation, innovation, automation, robotisation... All these “sensations” promise to increase productivity. Recently, they have also been joined by artificial intelligence, which is finding its place in economic production and promises to unlock growth potential again.

Written by Pavla Růžičková. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Czech National Bank.

References

Arce, O., Consolo, A., Dias da Silva, A., Mohr, M. (2023). “More jobs but fewer working hours”. The ECB Blog. 7 June 2023.

Ball, L., Mankiw, N. G. (2002). “The NAIRU in Theory and Practice”. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Volume 16, No 4, pp. 115–136.

Ball, L., Onken, J. (2021). “Hysteresis in unemployment: evidence from OECD estimates of the natural rate”. ECB Working Paper Series 2625.

Blanchard, O. J., Summers, L. H. (1986). “Hysteresis and the European Unemployment Problem”. NBER Macroeconomics Annual. Volume 1. MIT Press, pp. 15–78.

Blanchflower, D., Bryant, K. (2019). “A Case for Full Employment: Underemployment, the Falling NAIRU and the Costs of Excess Slack”. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Policy Futures. 10 June.

Botelho, V., Consolo, A., Dias da Silva, A. (2021). “Hours worked in the euro area”. Economic Bulletin, Article 1, Issue 6, 2021. ECB.

Brücker, H., Ette, A., Grabka, M. M., Kosyakova, Y., Niehues, W., Rother, N., Spieß, C. K., Zinn, S., Bujard, M., Décieux, J. P., Maddox, A., Schmitz, S., Schwanhäuser, S., Siegert, M., Steinhauer, H. W. (2003). “Ukrainian refugees: Nearly half intend to stay in Germany for the longer term” DIW Weekly Report. Volume 13, 25 July 2023. Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Berlin.

ECB (2002). “The unemployment-vacancy relationship in the euro area”. Monthly Bulletin, Box 6, December 2002. ECB.

ECB (2023). “ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area”. September 2023.

Fabiani, S., Mestre, R. (2000). “Alternative measures of the NAIRU in the euro area: estimates and assessment”. ECB Working Paper, No 17.

Garnitz, J., Sauer, S., Schaller, D. (2023): “Arbeitskräftemangel belastet die deutsche Wirtschaft”. Ifo Schnelldienst, 2023, 76, Nr. 09, 60-64.

Modigliani, F., Papademos, L. (1975). “Targets for Monetary Policy in the Coming Year”. Brookings Papers On Economic Activity. Volume 6, Issue 1, pp. 141–166.

OECD (2023). „Database Inventory 113“. OECD Economic Outlook. Volume 2023, Issue 1. June 2023.

Pošta. V. (2008). “The NAIRU and the natural unemployment rate – a theoretical view”. Research Study 1/2008. Ministry of Finance of the Czech Republic.

Rusticelli, E., Turner, D., Cavalleri, M. C. (2015). “Incorporating Anchored Inflation Expectations in the Phillips Curve and in the Derivation of OECD Measures of Equilibrium Unemployment”. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1231, OECD Publishing.

Keywords

euro area, unemployment, bankruptcies, NAIRU, Beveridge curve

JEL Classification

E24, J23, J63

[1] The specific values may differ slightly. The time series is subject to frequent revisions which, however, are usually only in the order of 0.1 pp.

[2] At the time of writing, the latest available data for all euro area countries were for 2023 Q2. The fastest-growing economies in the euro area were: Malta, Greece, Portugal, Croatia, Cyprus and Spain.

[3] At the time of writing, the latest available data were for September 2023.

[4] Still, all three crises had their economic losers, who fell through all sorts of safety nets and will not agree with the overall optimistic assessment.

[5] However, such declarations may only be provisional and do not always mean the end of business activity.

[6] At the time of writing, the latest available data were for Q2 2023.

[7] In Spain, the structure of bankruptcies is similar, the only difference being that the pre-COVID level was very soon surpassed by all sectors and, most recently, the number of bankruptcies declared in accommodation and catering, as well as in transport and storage, was almost five times higher than in the last quarter of 2019.

[8] And this has been the case since the very beginning of Eurostat's monitoring of this statistic. The time series of bankruptcies and registrations of legal persons have been available since 2015.

[9] Margins in the euro area have already been analysed in an article by Soňa Benecká, “How have firms’ price increases contributed to the current inflation in the euro area?” in the September 2022 issue of Global Economic Outlook

[10] ECB (2023).

[11] Garnitz et al. (2023).

[12] For low-skilled workers, this is only 15% in both sectors.

[13] The values differ depending on the statistics chosen. Data for total employment in the 20–64 age category were used here based on the European Labour Force Survey, which uses the concept of residency.

[14] In the same age group, the participation rate in the labour market rose from 75% to 78% between 2010 and 2019. After the COVID slump, it has returned to growth, the pace of which has been accelerating in recent quarters. The participation rate currently stands at 80%. Developments in other age categories (e.g., 15–64 or 15–74) are qualitatively similar.

[15] The employment rates are also above 80% in Malta and Estonia. Malta is exceptional in the way its labour market has changed significantly over the past 15 years. In fact, the employment rate in Malta was the lowest in the euro area (59%) in 2009. Since then, however, it has grown steadily and Malta is now in second place, just behind the Netherlands.

[16] This does not necessarily have to be purely a matter of higher worker morbidity in terms of their objective health (although it seems that the thoroughness of the anti-COVID measures at the beginning of the pandemic has inadvertently led to a significant reduction in the population’s defences against common viral infections, and the higher morbidity is also due to post-COVID syndrome (sometimes also called ‘chronic’ or ‘long’ COVID)), but also a shift in work culture in terms of a change in the perception of the state of health in which it is still permissible for a worker to be present at the workplace.

[17] There are multiple concepts for the equilibrium unemployment rate. For more information on this topic, see for example Pošta (2008).

[18] The authors of the term are Modigliani and Papademos (1975) and, unlike many others, it is an empirical rather than a theoretical concept of the approach to the equilibrium unemployment rate. For a more detailed description of the concept and its role in macroeconomic analysis, see e.g. Ball and Mankiw (2002). For a discussion of methods for estimating NAIRUs and their evolution over time, see e.g. Fabiani and Mestre (2000).

[19] Estimates dating back to before the creation of the euro area show a steady increase in the NAIRU from at least the 1970s to about the mid-1980s, and then again from 1990 onwards. See e.g. Fabiani and Mestre (2000).

[20] However, institutional factors reducing the structural unemployment rate also include legislative changes that result in the departure of some of the unemployed from the labour market, most often members of those social groups in which the unemployment rate is typically higher than the society-wide average. For example, a more generous approach to the allocation of invalidity pensions or more severe sanctions on criminal activities leading to a higher number of convicts may be examples of such policy actions. For more details, see Ball and Mankiw (2002). However, these structural factors were more likely to be reflected in the equilibrium unemployment rate in the deeper past.

[21] This phenomenon was first highlighted by Blanchard and Summers (1986). This term, originally drawn from physics, describes a situation in which the natural unemployment rate depends on the previously observed unemployment rate.

[22] At the time of writing, the latest available data were for September 2023.

[23] For the same reason, the use of the NAIRU to calculate potential output and fiscal position is being abandoned. For example, the OECD, which had previously published NAIRU estimates for individual countries, revised its methodology in 2018 to take into account anchored inflation expectations (see Rusticelli et al. (2015)) and renamed the time series as the “equilibrium unemployment rate”. However, in 2021, it also refrained from publishing it and no longer uses the NAIRU for its potential output calculations. (OECD, 2023)

[24] At the time of writing, the latest available data were from the October survey.

[25] For more details, see e.g. ECB (2002).

[26] At the time of writing, the latest available data were for 2023 Q2.

[27] This topic was discussed in more detail in the article by Martin Kábrt “Who will pay the COVID debt?” in the October 2023 issue of Global Economic Outlook.

[28] There are more than a million Ukrainian refugees in Germany, while a large proportion are children and women caring for them. According to the July study by Brücker et al. (2023), 18% of Ukrainian refugees in the 18-64 age group are already employed. The language barrier remains a major obstacle for the time being, but Germany is nevertheless providing language courses to refugees.