6. Euro adoption

The euro is the official currency of most countries of the European Union (EU). The countries that have adopted the euro together form a monetary union called the euro area, also known as the Eurozone. This grouping of European nations was formed in 1999 when the euro was introduced as invisible “book” money and the European Central Bank (ECB) began to implement a single monetary policy for euro area members. Initially there were eleven members, but in the following years the euro area has gradually expanded to include other countries.

Several countries established cooperation in the 1950s in an effort to prevent further wars from happening in Europe. This arrangement became the basis for the future European Union. The first pillars of European integration were the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community. The European Communities (EC) were created in 1967 through the merger of their executive bodies. The EC had a single Council (today the Council of the EU) and a single Commission (today the European Commission). At that time, there was already talk of introducing a common European currency.

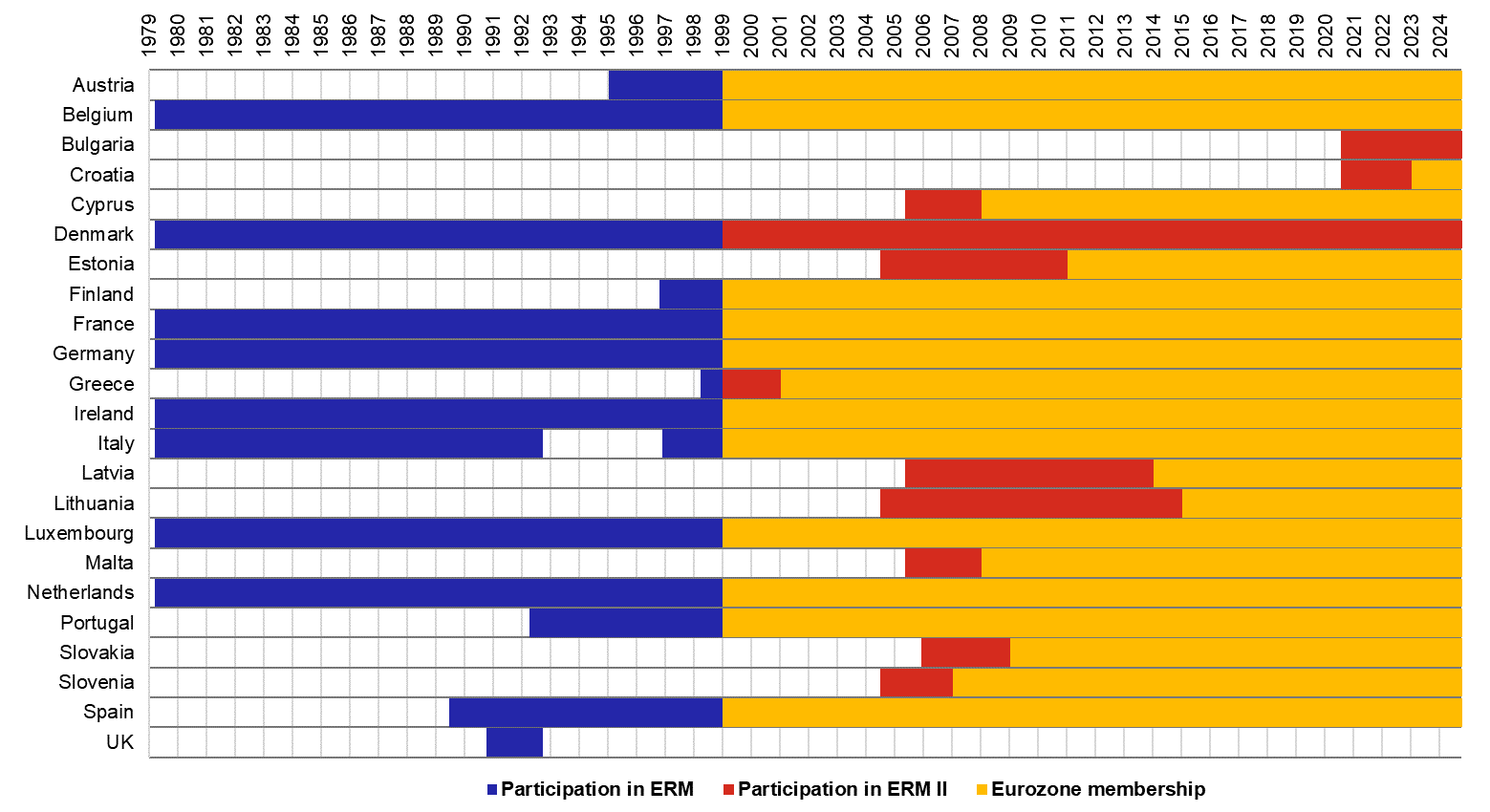

However, a number of political and economic obstacles had to be overcome on the way to the euro. The first stabilisation of the exchange rates was not achieved until 1979, when the European Monetary System (EMS) was introduced. This exchange rate regime, through the multilateral Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), controlled the fluctuations of the EMS currencies against the newly created European currency unit (ECU) – a basket unit of account based on a weighted average of the EMS currencies. Deviations from the central rate (ECU) of ±2.25% were tolerated within the ERM. The fluctuation band was widened to ±15% in August 1993 in response to currency turbulence.

In April 1989, on the basis of a mandate from the European Council, the Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union (better known as the Delors Committee) presented a proposal for three stages leading to Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The third stage was to involve the irrevocable fixing of exchange rates and the introduction of the euro.

An important milestone of European integration was the signing of the Treaty on European Union (also known as the Maastricht Treaty) in February 1992. The Treaty set out the rules for the future single currency and for foreign and security policy and closer cooperation in the field of justice and home affairs. Among other things, it defined the “Maastricht convergence criteria”, which are used to assess the progress made in the fulfilment by the Member States of their obligations regarding the achievement of economic and monetary union. The Treaty entered into force on 1 November 1993 (after ratification by the Member States), changing the European Communities into the European Union. The EU Treaty also included the establishment of the European Monetary Institute (EMI), a temporary institution whose aim was to pave the way for the single currency. On 1 June 1998, the EMI was replaced by the newly established European Central Bank.

The monetary union (euro area) was established on 1 January 1999, when 11 EU member states (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain) irrevocably fixed their exchange rates to the newly created euro. It was initially an invisible currency, only used for accounting and electronic payments. Euro cash was put into circulation in the 12 euro area countries on 1 January 2002 (Greece had joined the euro area in 2001). The euro area continued to expand in the years that followed. By 2024, it numbered 20 Member States.

Upon the creation of the euro area, the multilateral ERM was replaced by ERM II, in which the participating countries’ currencies are pegged to the euro. The standard ERM II fluctuation band remained at ±15% (the same width as the original ERM band after it was widened in 1993). Participation in ERM II is voluntary. Denmark has long been a participant. It negotiated a permanent opt-out from the euro in the 1990s during the Maastricht Treaty ratification process (other EU countries with their own national currencies have a temporary exemption – a “derogation” – from introducing the euro). In addition, countries aspiring to join the euro area (and thus meet the Maastricht convergence criteria) join ERM II.

Table – Countries’ stays in ERM and ERM II and membership in the euro area

The Czech Republic has been a member of the EU since 2004. By joining the EU, the Czech Republic undertook to adopt the euro in the future. For now, however, it retains its own currency and will not adopt the euro until it has met the Maastricht criteria and is economically ready for the euro.

The Czech Republic undertook to adopt the euro by signing the Act concerning the conditions of accession of the Czech Republic to the European Union. Prior to joining the euro area, the Czech Republic has the status of a member country with a derogation. Setting the specific date for joining is fully within the competence of each Member State. Ideally, however, the date should depend on the country’s degree of preparedness. Entry into the euro area is nonetheless conditional on the fulfilment of the Maastricht convergence criteria and on the compatibility of legislation.

The main principles concerning the adoption of the euro are described in The Czech Republic’s Updated Euro Area Accession Strategy, which was approved by the Czech government in 2007 and was prepared in cooperation with the Czech National Bank (the previous version of the Czech Republic’s euro area accession strategy was approved by the government in 2003).

The Czech Republic joined the EU in 2004. The euro area and the EU as a whole then experienced the Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent recession of 2008 and 2009, which was followed by a debt crisis in some euro area countries. In 2020 and 2021, the world was partly paralysed by the Covid-19 pandemic. Europe then faced the economic consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in particular a steep rise in energy prices. These and other events are affecting the ongoing processes of European integration aimed at strengthening economic and fiscal coordination and completing the banking union and the capital markets union. New institutions and rules are thus changing the shape of the euro area and the content of the obligation to adopt the euro. These facts also need to be properly assessed and considered in the decision on the timing of monetary union entry.

There are benefits and costs associated with adopting the euro which have to be taken into account. For example, the euro will make it easier for Czech households to travel, as there will be no need to exchange money when travelling in the euro area. The euro will also make it easier for consumers to compare prices between countries, which may increase competition between firms. The main benefits for businesses include the elimination of exchange rate risk and its associated costs. The costs of adopting the euro consist mainly in the loss of independent monetary policy, which would be conducted by the ECB after the adoption of the euro. In its decisions on the appropriate monetary policy settings, however, the ECB has to consider the condition of the euro area as a whole (deciding according to “European numbers”), not the condition of individual member countries (“national numbers”).

Economists agree on the fundamental benefits and costs of introducing the single currency. However, the significance of the various arguments may change over time or depending on the specific features of the economies concerned. The benefits include reduced international trade costs, in particular the elimination of exchange rate risk in relation to the euro area and the costs of hedging against it, as well as lower transaction costs for firms. Empirical studies generally find that the introduction of the single currency has a positive effect on international trade. However, there are considerable differences between the estimates, and there are even studies that find that euro adoption does not have a statistically significant effect on trade between euro area countries (for a more detailed discussion of the relevant literature, see the Theoretical Foundations of the Analyses in the Alignment Analyses). The elimination of exchange rate risk also facilitates planning for firms that trade internationally and makes the Czech economy more attractive to foreign investors. In the household sector, the costs associated with exchanging money when travelling in the euro area would be eliminated. Benefits could also stem from greater price transparency, which may stimulate competition.

However, euro adoption simultaneously entails risks arising from the loss of independent monetary policy and the stabilising role of a flexible exchange rate. Following euro area entry, Czech economic policymakers will have fewer tools to respond to the domestic economic situation. The European Central Bank is responsible for monetary policy in the euro area, but it sets a single policy according to the economic situation in the euro area as a whole. If the domestic economy deviates from the euro area average, the single monetary policy set according to the needs of the euro area as a whole may not be the right fit for it. This would lead to greater economic volatility. Such a situation arose, for example, after the Covid inflation surge.

Economic convergence is normally associated with long-term appreciation of the real exchange rate. This can take place either through nominal appreciation or through higher inflation in the domestic economy, or a combination of both. As the inflation target levels in the Czech Republic and the euro area are the same, the floating exchange rate of the koruna allows for this process to take place exclusively through nominal appreciation in the case of the Czech Republic. However, if the exchange rate were irrevocably fixed by adoption of the euro, this would no longer be possible and the real exchange rate could only appreciate through higher inflation in the Czech Republic than in the euro area. This represents an additional cost of joining the euro area. It should be noted, though, that the importance of this argument is gradually diminishing over time as the performance of the Czech economy converges to the euro area average and the rate of equilibrium appreciation of the real exchange rate of the koruna thus decreases.

There would also be costs associated with the change of legal tender itself, but these would be of a one-off nature.

The factors that will influence how advantageous joining the euro area will be for the Czech Republic include not only developments in the Czech economy, but also developments in the euro area and changes in its institutional set-up. These changes in the functioning of the euro area are translating into costs for the Czech Republic arising from new institutional commitments, including the obligations to join the banking union and the European Stability Mechanism.

The benefits of adopting the euro will outweigh the costs provided that the Czech economy is economically aligned with the euro area and its adjustment mechanisms are able to absorb any shocks that hit the Czech economy harder than other euro area countries. In this context, the CNB carries out detailed analyses once a year and publishes them in its Analyses of the Czech Republic’s Current Economic Alignment with the Euro Area.

For the Czech Republic to reap the benefits and minimise the costs of adopting the euro, a sufficient degree of convergence of the Czech economy to the euro area is necessary. In such case, the single monetary policy of the ECB will sufficiently meet the needs of the domestic economy. Conversely, if economic developments diverge too much across the euro area, there is a risk that a monetary policy set according to the needs of the monetary union as a whole will not be the right fit for a number of individual countries.

In order to assess the Czech Republic’s progress in creating the right conditions for euro adoption, the CNB each year prepares and publishes its Analyses of the Czech Republic’s Current Economic Alignment with the Euro Area. This document focuses on both structural and cyclical alignment. It analyses, for example, to what extent the Czech economy has converged towards the euro area in terms of the levels of GDP, prices and wages. It examines the sectoral structure of the Czech economy, the trade and ownership links of the Czech Republic with the euro area, the alignment of the economic and financial cycles, financial market convergence, exchange rate developments, spontaneous euroisation in the domestic economy and the alignment and transmission of monetary policy.

A high degree of economic convergence between the countries of a monetary union reduces the likelihood of asymmetric shocks and resulting different monetary policy needs. However, even in the case of imperfect convergence, other mechanisms can dampen asymmetric shocks in the absence of an independent monetary policy. One of these mechanisms is fiscal policy, which, if configured correctly (and with sufficient fiscal space), should have a countercyclical effect and thus be a stabilising element for the economy. Otherwise, it becomes a source of shocks itself and exacerbates macroeconomic imbalances. A sufficiently flexible labour market and a functional and resilient financial sector, for example, can also help to dampen asymmetric economic shocks. The ability of fiscal policy, the labour market and the banking sector to absorb asymmetric shocks in the Czech Republic is also examined in the Alignment Analyses.

The Alignment Analyses also contain an assessment of the economic alignment of the euro area countries, a description of institutional and economic developments in the euro area and the EU as a whole, and several thematic chapters that discuss selected aspects of euro area accession in more detail each year.

The conclusions of the analyses are also summarised in a joint document of the CNB and the Ministry of Finance entitled Assessment of the Fulfilment of the Maastricht Convergence Criteria and the Degree of Economic Alignment of the Czech Republic with the Euro Area, which is usually published once a year (although no assessment has been prepared in some years). This document focuses on the fulfilment of the Maastricht criteria, economic alignment and the situation in the euro area, including institutional developments. It also makes recommendations to the government of the Czech Republic regarding the timing of the adoption of the single European currency from the economic point of view.

The current assessment of the Czech economy’s alignment with the euro area and all past editions of the Alignment Analyses and the Assessment can be found here.

To adopt the euro, the Czech Republic must meet the Maastricht criteria. These criteria set limits on inflation, interest rates, exchange rate fluctuations, the government deficit and government debt. The aim of the criteria is to assess whether a country adopting the euro is macroeconomically stable and sufficiently prepared for the single currency.

Besides having to harmonise their legislation, EU Member States are required to achieve a high degree of sustainable economic convergence in order to join the euro area. This is formally assessed using the Maastricht criteria, which originated as part of the Treaty on European Union (also known as the Maastricht Treaty), which entered into force in 1993. Sustainable compliance with the Maastricht criteria is a necessary condition for joining the euro area. However, the mere fulfilment or non-fulfilment of these criteria cannot be seen as answering the question of whether, for a given country, the benefits of joining the euro area outweigh the costs or vice versa. This is a question that requires a much more comprehensive assessment, and even then it is difficult to find a clear-cut answer.

The Maastricht criteria focus on four areas: the achievement of a high degree of price stability, the sustainability of the government financial position, the stability of the exchange rate and the durability of convergence being reflected in the long-term interest rate levels.

The criterion on price stability assesses the rate of consumer inflation, which must not be more than 1.5 percentage points higher than the average of the three best performing EU (not just euro area) countries in terms of price stability. In practice, the inflation rate used to assess the criterion is calculated using the change in the latest available 12-month average of the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices over the previous 12-month average. Outliers – countries whose inflation rates are significantly lower than those of the other Member States and whose price developments have been strongly affected by exceptional factors – may be excluded from the calculation before the reference value is set.

The criterion on the government financial position requires long-term sustainability of the government financial position. The criterion is normally assessed using two reference values: a general government deficit of no more than 3% of GDP and general government debt of no more than 60% of GDP. Formally, however, the criterion is fulfilled if the country is not subject to an excessive deficit procedure (EDP). An EDP is usually opened if the country exceeds one of the reference values, but there may be exceptions. For example, after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the “general escape clause” was applied in the EU until 2023 and no EDP was opened even for countries that exceeded the reference values. Similarly, an EDP does not need to be launched if the general government debt-to-GDP ratio is falling at a sufficient pace towards the 60% reference value. In such cases, therefore, the criterion on the government financial position can be formally fulfilled even if one of the reference values is exceeded.

The criterion on participation in the exchange rate mechanism requires a successful, at least two-year stay of the national currency in the exchange rate mechanism (ERM II). Before a country joins ERM II, a central rate of the domestic currency against the euro is set, against which exchange rate fluctuations are monitored. The mechanism assumes that the exchange rate will move within a set fluctuation range without devaluation of the central rate and without excessive pressure on the exchange rate. The interpretation of this criterion is not entirely clear – the standard ERM II fluctuation band is ±15% around the central rate, but at the time the Maastricht Treaty was approved the fluctuation band of the then ERM was only ±2.25%. Based on past experience with the approach of the European Commission and the ECB to assessing the fulfilment of the exchange rate criterion, it can be surmised that an asymmetric fluctuation band in the range of -15% to +2.25% is considered smooth fulfilment. In other words, the assessment is more benevolent towards deviations on the stronger side. In addition, a number of other factors are considered when assessing the fulfilment of the exchange rate criterion, for example the size and duration of the deviations of the exchange rate from the central rate and the impact of any foreign exchange interventions on the exchange rate. As for the central rate itself, even past revaluation has not been an obstacle to successful fulfilment of the criterion (for example, Slovakia revalued the central rate twice during its stay in ERM II before joining the euro area). Overall, then, there is some room for discretion in the examination of the fulfilment of the exchange rate criterion.

The criterion on interest rate convergence aims to capture the durability of a country’s economic convergence. Meeting the criterion requires that, observed over a period of one year before the examination, the government bond yields of the country under assessment with ten years’ average residual maturity do not exceed by more than 2 percentage points the average government bond yield in the three best performing EU countries in terms of price stability (see also the discussion of the price stability criterion above).

More detailed information, including the Treaty provisions for each criterion, is provided in Appendix A of Assessment of the Fulfilment of the Maastricht Convergence Criteria and the Degree of Economic Alignment of the Czech Republic with the Euro Area.

Several years will pass from the moment the Czech government sets the euro adoption date until the euro is actually introduced. One reason for this is that the Czech Republic must meet the Maastricht exchange rate criterion, which requires at least two years of successful membership in the ERM II exchange rate mechanism. Only after successfully staying in ERM II and meeting other conditions will it be certain that the Czech Republic will introduce the euro and the final phase of preparations, such as the minting of euro coins, can thus begin.

The key domestic player in the euro area entry process is the government. It is responsible for deciding when to apply to join ERM II and subsequently the euro area. However, given that legislation needs to be amended both before ERM II entry and before euro adoption, neither ERM II nor the euro area can be entered without the active consent of the parliament of the Czech Republic. The CNB has an analytical and advisory role in the decision on the timing of ERM II and euro area entry. If the euro area entry process were initiated, the CNB would provide assistance in the various steps necessary for the process to run smoothly.

The government’s decision to start the process of joining the euro area would be followed by preparations for ERM II entry. Consultations between the candidate country and the ERM II parties (the ECB, the euro area member states and the countries currently participating in ERM II) and the European Commission would clarify the conditions the country has to meet before joining ERM II, for example in the area of reforms and legislative changes.

Once the conditions have been met and the European Commission and the ECB give the go-ahead, the country can formally apply to join ERM II. Just before the actual entry, a central exchange rate would be set. The central rate determines the fluctuation band for exchange rate movements during participation in ERM II. While in ERM II, the country must also fulfil any other conditions set for subsequent entry into the euro area.

To join the euro area proper, the country must meet the Maastricht convergence criteria and achieve legislative compatibility, both of which are assessed every two years in the regular Convergence Reports of the European Commission and the ECB in the case of EU Member States with their own currencies (except Denmark). At the request of a Member State, an extraordinary Convergence Report may be delivered outside the biennial schedule. If the country fulfils all the conditions, including a successful stay in ERM II (formally, the European Commission’s Convergence Report is key to this examination), the European Commission will propose that the EU Council lift the Member State’s derogation. The EU Council will then take a decision on this and set the conversion rate at which the country will adopt the euro. Other European institutions and euro area countries are also formally involved in this process.

Euro area entry would then be preceded by related technical preparations, for example, the production of euro cash and the introduction of dual prices (in korunas and euros). The Czech Republic’s Updated Euro-Area Accession Strategy, which is still in force, assumes the simultaneous adoption of cash and book euro.

The process of joining the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and – if it does not happen earlier – joining the banking union and meeting the related requirements would take place in parallel to entry into the euro area. Joining the euro area would also involve, among other things, paying up the Czech Republic’s share in the ECB’s subscribed capital in full, transferring foreign exchange reserves and making contributions to reserve funds.

From the above steps, it is clear that joining the euro area is a relatively complicated process and would probably take at least three years from the initial government decision. In terms of the timing of the steps, the CNB has long held the view that staying in ERM II for longer than is strictly necessary to meet the relevant Maastricht criterion and subsequently prepare for the introduction of the euro would be macroeconomically disadvantageous for the Czech Republic. It should therefore only enter ERM II with a clear intention to join the euro area within a specific time frame. The ERM II entry date should be derived from the target date for euro area entry. This position is in line with the aforementioned The Czech Republic’s Updated Euro-Area Accession Strategy.

Indicative timetable for joining the euro area

Although the Czech Republic will not be able to set its own monetary policy after adopting the euro, it will participate in the ECB’s decision-making. The CNB Governor will be a member of the ECB’s main decision-making body, the Governing Council, and will participate in the voting on euro interest rates. In this voting, however, he or she will have to subordinate the interests of the Czech Republic to those of the euro area as a whole. After euro area entry, the CNB will continue to exercise a number of powers that will not be transferred to the ECB.

In the event of euro area entry, the CNB would no longer be able to set its own monetary policy. However, it would participate in the ECB’s common monetary policy. The CNB governor would become a member of the ECB’s main decision-making body – the Governing Council (consisting of the governors of the central banks of the euro area countries and the six members of the ECB’s Executive Board) – and would participate in the voting on monetary policy in the euro area as a whole. When voting, however, the members of the Governing Council have to subordinate their own national interests to those of the euro area as a whole. The CNB would also become involved in the preparation of euro area macroeconomic projections, which are a key input to the Governing Council’s decision-making. The forecasts are prepared four times a year; twice a year they are produced by individual Eurosystem central banks, of which the CNB would be one.

After euro area entry, the CNB would continue to exercise powers that would not be transferred to the ECB (although it would collaborate with the ECB in these areas). These competences would include, for example, macroprudential policy, part of financial market supervision (under the Single Supervisory Mechanism, the ECB would directly supervise banks identified as significant, while the CNB would be in charge of supervising other institutions), issuance of “Czech” euro coins, payments, and consumer protection in the financial market.